The Peninsula

How is Pyongyang Controlling its Won?

By William B. Brown

Like many North Korea questions, we don’t know but we have some ideas. All of them regarding finance must be worrisome to Kim Jong-un and his cabinet as they try to deal with a near Chinese embargo on their exports that is likely causing an outflow of reserve dollars needed for essential imports, and even for maintaining stability in the domestic money supply.[i] But the apparently pegged won also offers excellent opportunities for continued growth of the market side of the country’s bifurcated economy, whether or not desired by the regime. Don’t hold your breath but some clues as to the regime’s policy direction might show up early next month when the government’s annual budget is presented, always a rubber stamp exercise with little data. The observed fact that ever scarcer dollars are competing with won in everybody’s wallets, however, should be drawing attention to how Pyongyang is financing its enormous bureaucracy and military. Credibility becomes important and a mistake by the regime can create a dangerous situation in which the public suddenly tries to sell its won in exchange for hard currency, and the won collapses in panic. Since a significant part of the government’s needs must now be met by paying dollars, the impact on public finance could be catastrophic.

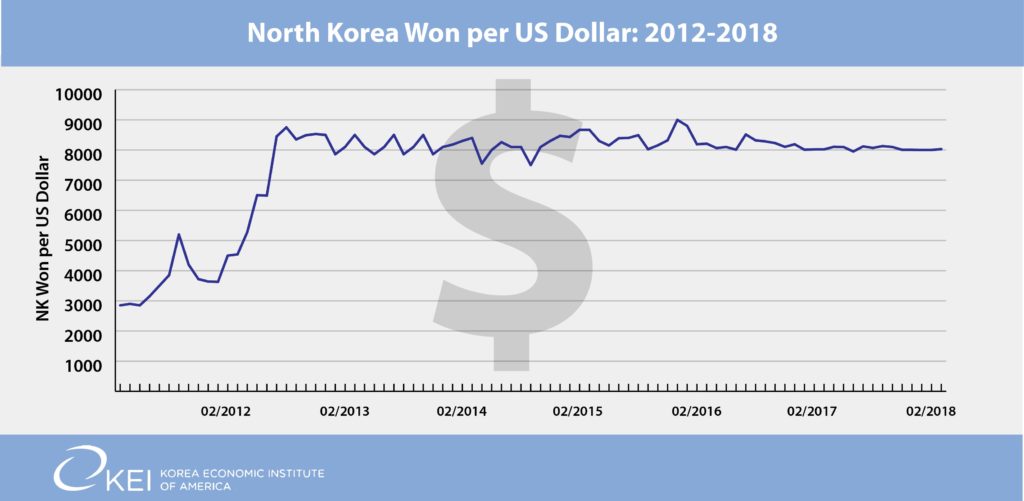

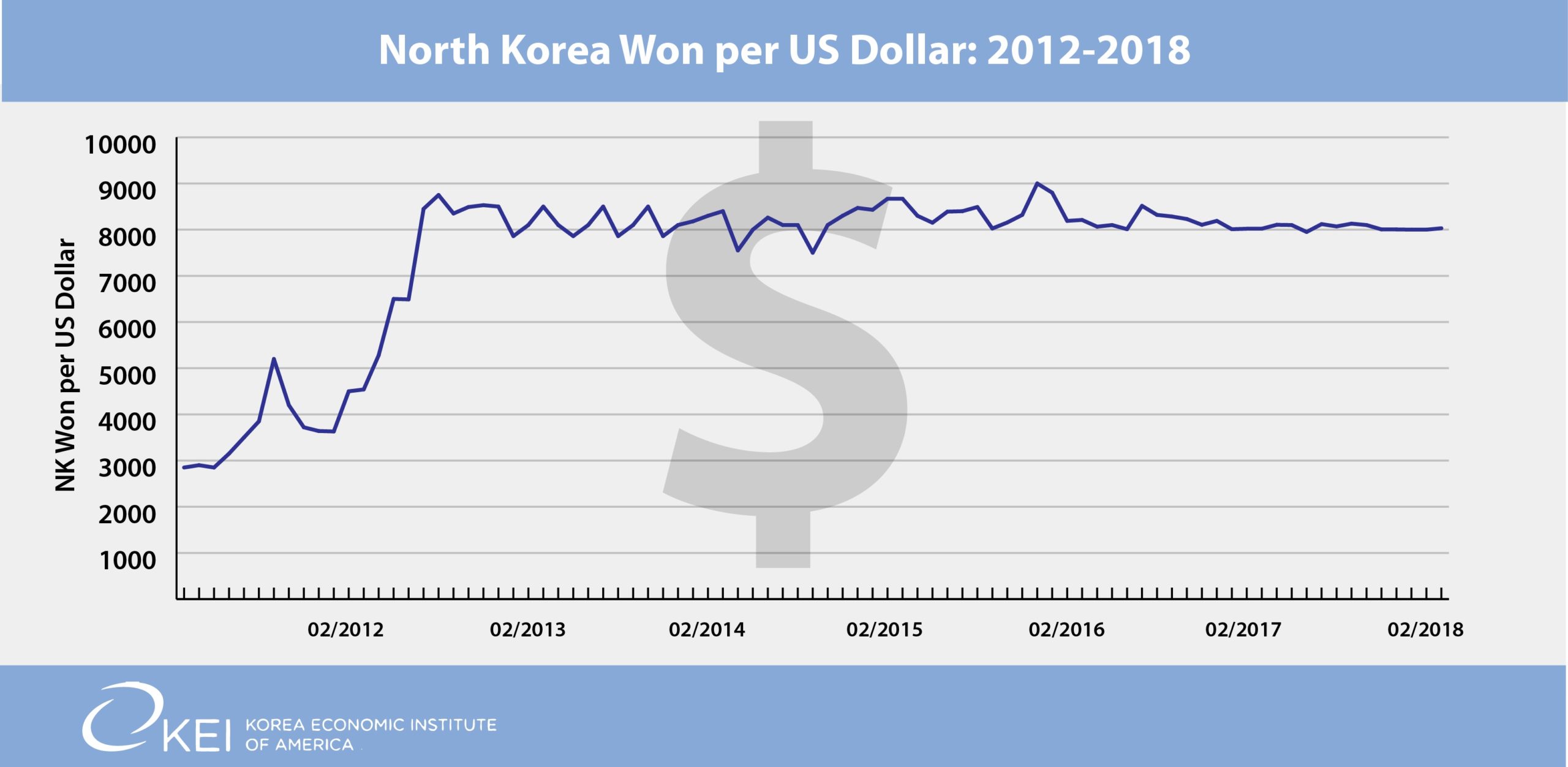

The North Korean won, as reported by Daily NK each week, has been remarkably stable for the past five years, after falling precipitously for a decade prior to Kim Jong-un taking power. (The graphic portrays the value of the dollar so up is down for the value of won.) Most remarkable is its even greater stability in the past six months, even as the country’s observed trade deficit has grown spectacularly, presumably creating an outflow, and thus a shortage, of foreign exchange. One might consider this monetary stability, also shown in stable prices for rice and corn, as the young leader’s greatest accomplishment so far, and it does speak to the skills and knowledge of his monetary team. The likely tension, given a growing storm, however, suggests a snap may be coming.

An analogy might be a boat, tied to a dock on tidal waters, much as I experienced upon moving to Virginia Beach many years ago. Our house was on a tidal canal and I soon bought a small boat, tying it to the dock. My neighbors quickly told me, however, don’t use your instinct and tie it too tight. If you do, a rising tide will, as the saying goes, raise all boats except yours, and yours will sink. If you are lucky the line will break, and it will float away. Flexibility is important; very useful advice. The same can be said for an exchange rate. The won-dollar rate, not budging despite apparent big changes in trade and foreign payments conditions—the rising or falling tide—might either snap letting the economy go free, or the economy might sink and its rulers with it.

Why is this suddenly important? In decades past the exchange rate would not be an issue for North Korea since its currency was permanently fixed, as were currencies of all socialistic, “command economies,” and not very meaningful. No forces of supply and demand were on the rates and they had nothing to do with imports or exports. Exchange rate theory says that a government can fix an exchange rate in this way but it then must give up one of two other normally desired characteristics of a monetary system, openness to capital flows (in effect the ability of its citizens to trade and hold foreign money, and for foreigners to invest and use its money) or freedom in setting its own monetary policy, for instance setting short term interest rates or financing a fiscal deficit. For a socialist country this was an easy choice as it did not want to have open capital markets. They all chose fixed rates and severe capital controls, enforcing tight limits on their citizens use of money. Most developed countries today choose to have free capital flows, given the improvement in economic efficiency they allow, and independence in monetary policy, so somewhat reluctantly they let their exchange rates float freely. Very few states choose the third option, a fixed rate, free capital flows, and no independence of monetary policy. Hong Kong, with its currency board, is one of few examples, fixing its dollar at 7.8 per U.S. dollar and holding that rate for more than 30 years, while letting its monetary policy be determined, in effect, by the Fed. A trade surplus that would raise demand for the Hong Kong currency and try to make it more valuable, is automatically countered by a fall in interest rates, which reduces demand for currency and increases consumption and imports. Without government interference, the exchange rate holds firm and the real economy, so to speak, adjusts. Hong Kong adopted this system to protect itself from Chinese monetary policy as it was being returned to China’s jurisdiction in 1997 but, except during the Asian Financial Crisis ten years later, it has worked well so has been maintained.

I would venture to say, North Korea now has joined this elite club of fixed exchange rates and surprisingly open foreign exchange markets, ironically linking the top and bottom countries in Heritage’s Index of Economic Freedom. Only I doubt it lets interest rates adjust to maintain the won peg; that would be entirely too capitalistic, and those rates would have to be extremely high, jumping ever higher with each nuclear test. It must be doing something else.

Its observed but unofficial solution is not what one would expect from a such a control conscious regime, allowing citizens freedom to use foreign currency and thus giving up its money monopoly and freedom of monetary policy. Defector reporting puts at about 50 percent the value of normal transactions done in the domestic currency versus those done in U.S. dollars or Chinese yuan. This means that a typical North Korean will have two or three currencies in his wallet, or on his electronic debit cards. For a taxi ride he may need two U.S. dollar bills, for household goods in the market he may use RMB, for any payments to the government (except bribes) he will use won. If he is paid by the government, he will receive won but he can change that for hard currency in market places. For a down payment on a long-term unofficial and in theory illegal lease on an apartment, he will need something like $30,000 in U.S. cash which he might cobble together by borrowing from friends or relatives and from his profits dealing as a merchant.

With citizens able to freely convert won to hard currency in this way, and vice versa, the government must have a mechanism to enforce the pegged rate. If we rule out interest rate changes by the central bank, there are several possibilities:

- Direct intervention in markets, selling official reserves of dollars or RMB whenever the won starts to slip. As long as the public believes the state has ample reserves, this is not a costly operation and the bank might even make some profits. But if there is a loss of public confidence, say in a realization that reserves are small compared to outstanding won, there can be an avalanche in favor of the dollar and the central bank’s foreign exchange will quickly disappear. (In Hong Kong this is avoided by 100 percent reserves, that is for every 7.8 Hong Kong dollars printed, 1 U.S. dollar must be deposited in the Monetary Authority’s accounts.) North Korea’s system is so opaque; however, no one will believe how much reserves they have. This means a slight rise in the dollar might be a signal that reserves are being depleted, as they must be given a persistent current account deficit and the bank might be losing it power.

- Supporting the won by not printing more of it, that is severely controlling expansion of the won money supply. This scarcity would make won valuable, compensating for the increasing scarcity of dollars as the current account continues in deficit. This creates big issues for the real economy, however, as it would likely diminish the state’s ability to provide credit to state enterprises to invest, or to raise government or military payments. Forced to run state surplus, expenses would be reduced and income increased, wherever possible. Deflation, rather than inflation might become a problem, a high cost to any debtor.

- Inducing an inflow of foreign capital, that is letting a rise in a capital account surplus compensate for the observing rise in the current account deficit, netting out any pressures on the won. This would be difficult in the current sanctions environment, and the state’s poor record in paying back debt. But it might be happening on the private side, given an imbalance in capital freedom in North Korea compared to capital controls in its giant next-door neighbor. Chinese speculators might find they can increase returns by buying North Korean RMB denominated assets, getting around Chinese rules which generally discourage foreign use of RMB currency, clearly abused in North Korean markets. Like a border casino playing by different rules, North Korea’s lax enforcement of capital might be drawing in more Chinese money than we might expect.

I suspect element of all three are happening, the last one most interesting since it would be more market rather than policy related and could shift quickly if such entrepreneurs and speculators reversed course and took their money home. One relatively easy, but ideologically damaging solution, would be for the state to finance itself by selling state property and licenses. Unable to pay a military battalion, for example, it might authorize the unit to build an apartment bloc in Pyongyang, allowing it to buy the materials on the market and use its conscript labor to build and offer hundreds of these at perhaps $30,000 a unit. Another way would be to clamp down as much as possible on imports, and in January imports from China did show about a 30 percent drop according to Chinese customs data. And every effort would be made to increase exports of the few products that are not embargoed.

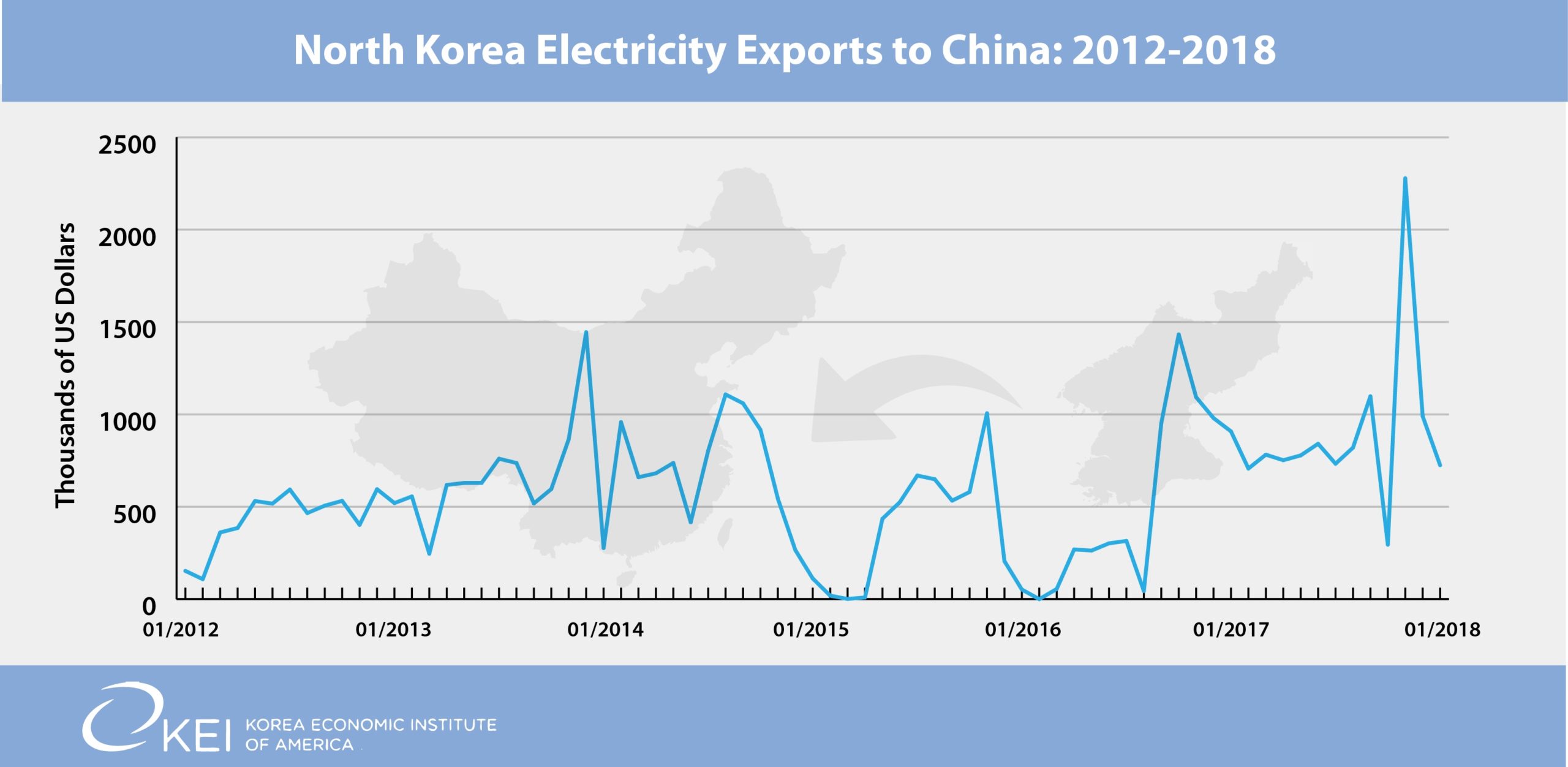

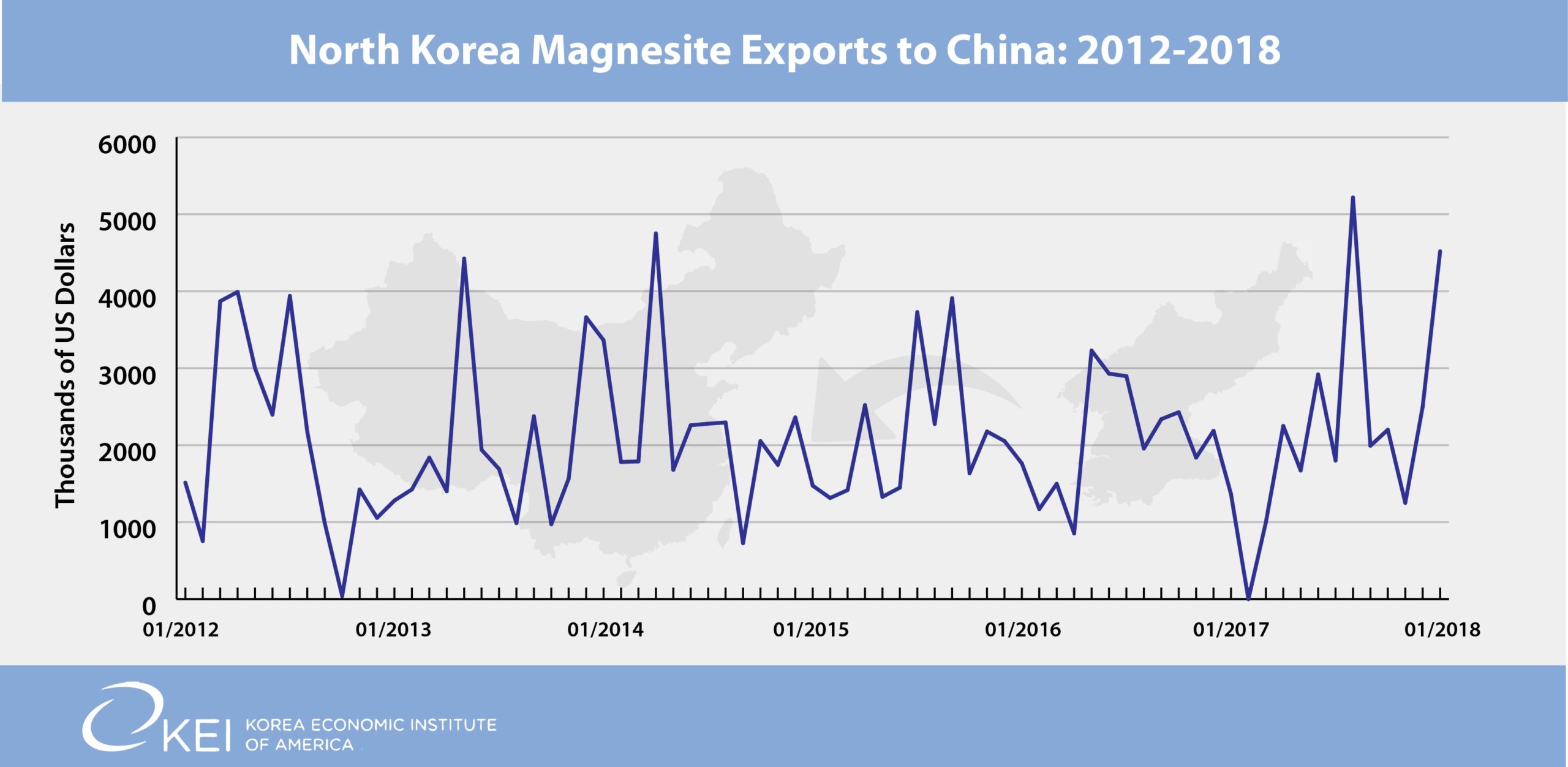

Exports of earth materials, graphite and magnesite, for example, therefore, have been strong in recent months, but still add to only about $ 8 million in January. And nets sales of electricity have risen despite perennial domestic power shortages. Interestingly, North Korea can charge an internationally competitive rate, about 4 cents a kilowatt hour to Chinese customers just over the border. Considering domestic customers pay next to nothing, one can see how optimum decisions can become distorted, with vital needs, even for pumped water, going unfilled as power flows north. Daily NK reports that meters are being installed in Pyongyang housing to allow electricity to be charged for usage, a measure that would help rationalize its use and provide income to the power plants, but electricity intensive heavy industry, which was built to use cheap power, could be devastated as a result.

For many years I have argued that North Korea’s abuse of its monetary system sets it apart from even Maoist China and has made Chinese style economic reforms exceedingly difficult. The people don’t trust the money, and for good reason, since inflation and won devaluation wiped out its value. And even friendly foreigners would not lend the state money since it never repaid its debts. This meant the citizens had no way of acquiring financial savings and were thus forced to live hand to mouth, an essential component of the state’s control system. With no savings and no money to be earned, everyone was at the mercy of the Worker’s Party for his next meal.

But this has now changed, dramatically. People have money and they are saving it, in one hundred-dollar bills. And the government, in need of imported kerosene, must be scrambling to get those dollar bills back. It’s the kind of tension I like to see. Maybe we can create more of it.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Mike Rowe’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[i] Other solutions might be possible as well. I would appreciate alternative views and comments on this rather complex topic especially from experts in monetary theory who might not normally pay attention to North Korea.