The Peninsula

Economic Allies: Highlights of the Past Seventy Years of U.S.-Korea Economic Relations

In celebrating seventy years of their security alliance, the United States and Korea exemplify the very best of what a robust economic partnership looks like. With terms like “friend-shoring” and “economic allies” increasingly making their way into beltway policy language, no reflection of the past seventy years of the U.S.-Korea alliance would be complete without examining exactly what it means to be an economic ally.

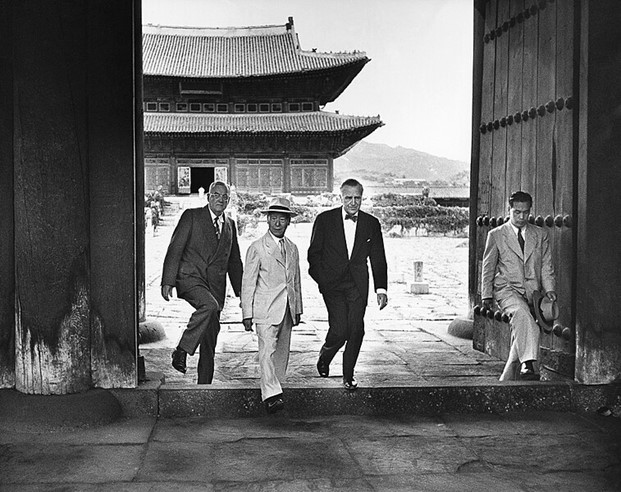

Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian Affairs Walter S. Robertson, South Korean President Syngman Rhee, and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles walk through Gyeongbokgung Palace in Seoul after finalizing the armistice agreement in 1953.

The long history of economic relations has been punctuated by milestone achievements such as Korea becoming an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member in 1996, an FTA partner of the United States in 2012, and this April’s visit to the United States by President Yoon Suk Yeol culminating in billions of dollars of investment announcements. As it stands today, the United States is South Korea’s second largest trading partner behind China for both imports and exports, while South Korea remains the sixth largest goods trading partner for the United States. Furthermore, in 2022, the United States surpassed China to become Korea’s number one goods exports trading partner for the first time in eighteen years. In some specific sectors, they are indispensable to one another. In 2022, Korea was the number one export destination for U.S. beef, while the United States is increasingly a top destination for Korean vehicle exports. This has all come a long way from the astonishing journey Korea made from being an aid recipient of the United States to a major investor in its economy.

Post-War Reconstruction and Redevelopment

In the initial years, the focus of Korea’s trade policy centered around import substitution and the promotion of domestic industries through industrialization and export promotion. Korea’s focus on being a trade partner to the world predates the establishment of the Republic itself. Korea’s premier trade organization the Korea International Trade Association (KITA) was founded in 1946 and by early 1948 already had an overseas office in Tokyo, which was followed by a New York office in 1967. Contemporaneous with the founding of the alliance in 1953 was the creation of the American Chamber of Commerce in Korea, which from its outset has existed to develop investment and trade between the United States and Korea.

After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Korea’s domestic situation took full precedence, prompting both countries to change their focus in Korea to reconstruction and development. This resulted in the United States leading the development of the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA), which was a significant driver in rebuilding Korea’s war damaged industries. In order to provide economic stabilization, the “Meyer Agreement”, signed May 24, 1952, also pushed to establish a Combined Economic Board to face issues regarding inflation and foreign currency exchange. Clarence E. Meyer, who presided over the agreement had served as the Director of the Economic Cooperation Administration in Korea and as Special Envoy where he was influential in providing development assistance to Korea’s chaebols.

The signing ceremony for the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA) between John B. Coulter and Prime Minister Baek Du-jin.

Following the armistice of the Korean War in July 1953, the focus of Washington’s official development assistance quickly turned its attention to Seoul. According to Kevin Gray and Jong-Woon Lee, between 1949 and 1961, the United States provided more aid to South Korea ($4.86 billion) than it did to the entire Latin American and Caribbean region during the same period. This was exemplified by the development loans and reconstruction assistance programs offered by the United States which helped to revive Korean industries. The Meyer Agreement was followed by another landmark agreement, the “U.S.-Korea Joint Economic Committee Agreement on Economic Revival and Economic Stability” in 1953 which provided additional reconstruction funds and exchange rate normalization. Later, the “Korea Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation Treaty” signed in November 1956 by Ambassador Walter C. Dowling and Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs Cho Chung-whan served as the precursor further agreements involving economics and trade.

In the wake of the armistice, Korean infrastructure began to be revived by loans secured from U.S. government agencies such as the U.S. International Cooperation Administration and from the 1960s onwards, Korea’s economy rebounded in what later became known as the “Miracle on the Han River.” Korean exports to the United States surged, and the economy transitioned from being primarily agricultural to being supported by a growing light and heavy industry. U.S. agricultural exports such as rice were critical for Korea as it transitioned from being an agricultural to an industrial economy and President Park Chung Hee worked to use rice imports from the American Food for Peace program to keep wages at prices low enough to support the attractiveness of Korean exports abroad. Similarly, Korean agricultural exports such as ginseng found high demand in American markets, and became an important part of Korean trade promotion.

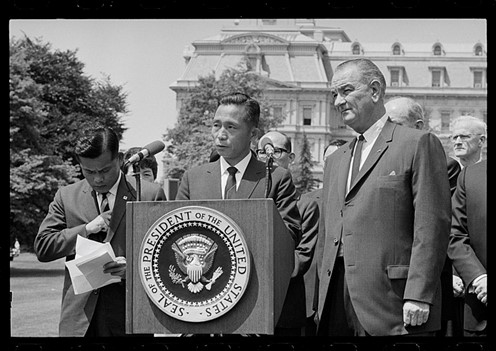

President Park Chung Hee speaks near the White House in May 1965 as President Lyndon Johnson looks on.

On the manufacturing side, when Japan entered into a textile agreement with the United States in 1963 (later becoming the multilateral Multifiber Arrangement), Korean manufacturers filled the gap left by Japanese exporters and found their footing in America’s markets for textiles. This began the first of Korea’s many headways into the American markets as Korean industries began to reach a degree of global prominence. American investment in Korea also began to pay off in very tangible ways. In the Vietnam War, Korea was a critical partner for American troops in the region through its provision of offshore supplies to the combat theater supplied by its light and heavy industries. War related revenue is thought to have contributed up to $185 million for South Korea in 1967 alone, which was a significant driver of Korea’s GDP growth as well as its ability to acquire hard currency, foreign loans, and investment. The export of rice through the U.S. Food for Peace program also acted as an informal payment mechanism to use with Korea for their support in Vietnam.

Trade Diplomacy and the Asian Financial Crisis

Benefitting from the redevelopment of Korea’s light and heavy industries, Korean textile and manufacturing industries began to flourish. Korea’s textile dominance in the United States led to the some of the first trade negotiations between the United States and Korea in the 1970s. In an effort to convince Korea to restrict their textile exports to the United States and thereby appease the U.S. textile industry, President Richard Nixon sent former Secretary of the Treasury David Kennedy to Seoul to negotiate export restraints. The meeting concluded with the United States promising to increase their rice aid to Korea by $175 million in return for Korea agreeing to voluntary export restraints on textiles, concessions which reportedly did not become public knowledge until three years afterwards. This became substantiated by the signing of the first “Textile Pact” between the United States and Korea in 1972. Another milestone came in 1977, when the United States and Korea agreed to a four year quota on the number of Korean non-rubber shoe exports to the United States, seeking to remedy what was seen by U.S. manufacturers as injury to U.S. domestic workers. Negotiations led by special trade representative Stephen Lande initially faced difficulty, but successfully concluded with concessions to both Korean and U.S. shoemakers. Korea was able to avoid the tariffs initially recommended by the International Trade Commission by instead receiving a quota, which allowed U.S. shoe manufacturers to receive a degree of relief from the increase in shoe imports from Korea and Taiwan.

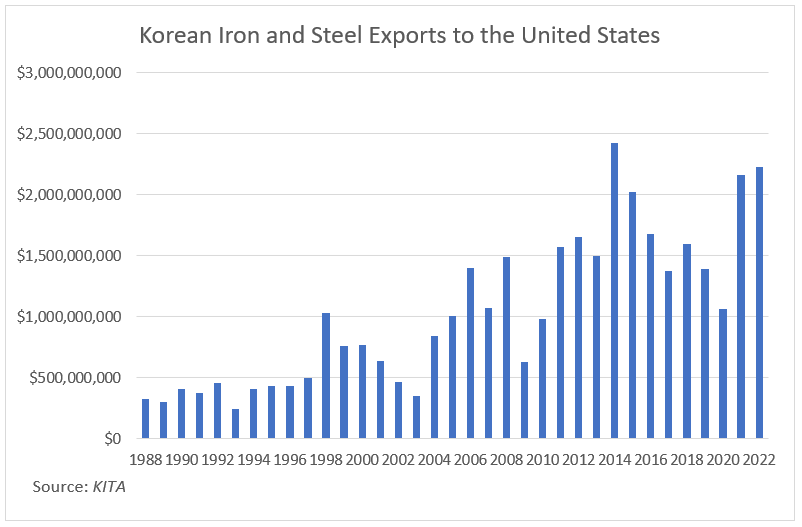

Korea’s heavy industries also began to gain prominence. Large steel mills, which had been established in the 1970s with government support, began to come into their own as global exporters and by the 1980s Korea’s largest steelmakers were well underway exporting steel products to the United States. This era marked Korea’s debut as a global technological and industrial power and Korean semiconductor companies like SK Hynix and Samsung were making headway into the global semiconductor market before becoming leading producers in the 1990s.

More organizations were created to promote U.S.-Korea trade such as the U.S.-Korea Business Council in 1987 as the focus of bilateral discussions increasingly targeted issues relating to market access and trade liberalization. With Korea’s full-scale industrialization underway, Washington and Seoul began negotiating steel agreements culminating in the April 1990 Steel Trade Liberalization Agreement, which was the first of many future dialogues between the United States and Korea on issues relating to steel. By 1995, Korea had become the world’s 11th largest economy and its contemporaneous accession to the World Trade Organization also gave it an outlet to pursue trade remedies. Joining the OECD in 1996 similarly showcased a remarkable step in its transformation into becoming an advanced economy as it was the only former OECD aid recipient to subsequently become an OECD development donor.

But the celebration was short-lived. By 1997, Korea was deep in the maw of the Asian Financial Crisis and in desperate need of a bailout. Shortly after President Bill Clinton urged “tough medicine” for South Korea conditional on the Korean government accepting recommended changes to their economic system, U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin helped to steer a $57 billion bailout package from the IMF while the United States along with Japan, Germany, and other nations agreed to loan Korea $8 billion. Similarly, then Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers pushed to convince wholesale banks from G7 countries to delay loan payments for Korea while New York Fed Chairman William McDonough persuaded American banks to renew Korea’s loans. Another important figure of the crisis was William R. Rhodes, who from his perch at Citibank negotiated debt solutions for the liquidity strapped Korean banking system. Acting out of patriotic duty, many Korean citizens even offered to sell their gold jewelry in response to government appeals to offset the currency devaluation which occurred because of the crisis. As an outcome of the bailout negotiations, Korea agreed to open its capital markets, lower trade barriers, and reform its banking structure.

Then U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin meets with fellow G7 finance ministers at the G7 Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting on October 3, 1998, in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis.

Korea in the Twenty-First Century

Following the resolution of the Asian Financial Crisis in Korea, the attention turned again towards trade negotiations. In the lead up to the first negotiations of the U.S.-Korea (KORUS) FTA in 2006, Korea surpassed countries like France and Italy to become the United States’ seventh largest trade partner while U.S.-Korea trade reached a record $75 billion and the United States became Korea’s second largest supplier of foreign direct investment (FDI). Korea’s specialization in semiconductors, electronics, automobiles, and machinery were all examples of the importance of forming an FTA, as was Korea becoming a major market for U.S. agricultural products such as beef. On April 1, 2007, negotiations led by Assistant U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Wendy Cutler resulted in the signing of the FTA on June 30 of the same year.

Original features of the FTA included the removal of most tariffs related to bilateral trade, removing obstacles to trade in the services market, and considerations for a potential future accounting of goods produced in the Kaesong Industrial Complex. Ratification was delayed by subsequent additional negotiations before modifications were agreed to on December 3, 2010, and signed on February 10, 2011. The additional negotiations ceded, inter alia, in concessions including a tariff phase out extension on certain U.S. pork exports and specific tariff removals and phase outs on imports of Korean passenger cars and trucks, while no changes were made to major issues such as beef exports (a separate commercial agreement was reached to resolve this issue). Immediately following the December 4, 2010 modifications, President Obama said on his prior reluctance to sign the agreement: “I didn’t agree to it then for a very simple reason: The deal wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t good enough for the American economy, and it wasn’t good enough for American workers.”

President Obama speaking with USTR Ron Kirk on November 11, 2010 prior to final round negotiations on the ratification of the KORUS FTA in Seoul.

Presidents Donald Trump and Moon Jae-In sign a revised U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement in 2018.

After ratification by both countries’ governments, the FTA went into effect on March 15, 2012, but further renegotiations initiated by the Trump administration in 2017 under Article 22.2 of the agreement resulted in additional modifications in 2018. The 2018 talks between USTR Robert Lighthizer and Korea’s Minister for Trade Hyun Chong Kim altered terms relating to auto exports, pharmaceutical pricing, and corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards.

Among other things, Korea agreed to extending the phase out of the United States 25 percent tariff on imports of light trucks, allowing greater access for U.S. automobiles in the Korean market, and recognizing U.S. standards on auto parts while ensuring non-discriminatory treatment for U.S. pharmaceutical exports. Separately following the agreement, the United States agreed to an exemption of the Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 tariffs on Korean steel imports to the United States, instead making them subject to a quota equivalent to 70 percent of their average import volume from 2015 to 2017.

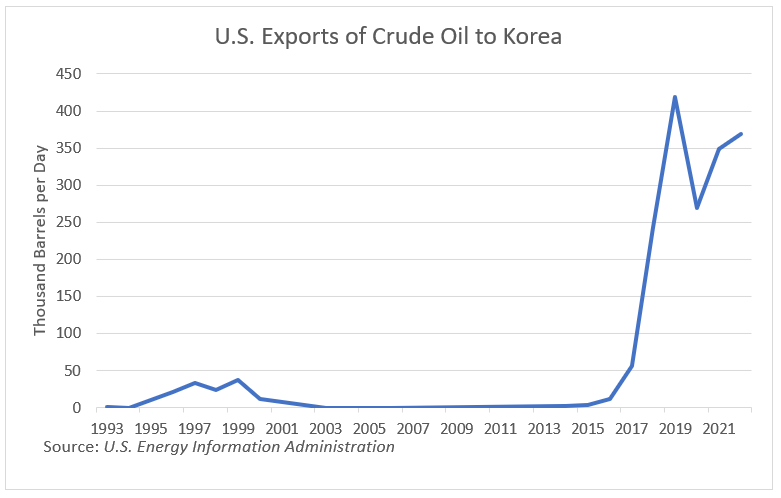

Since then, U.S. trade with Korea has continued to grow and new shared avenues are formed every year in areas such as technological cooperation, battery manufacturing, and energy. On the energy side, as a result of the United States repealing its crude oil export ban in 2015, the United States has risen to become Korea’s number two crude oil supplier, harkening a new era in energy partnership that now also includes the production of solar panels and electric vehicle (EV) batteries.

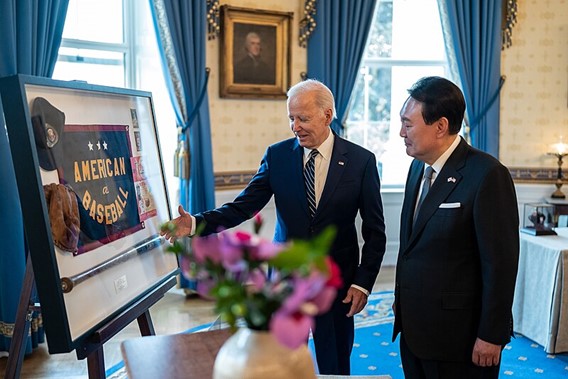

President Biden hosts President Yoon to the White House, April 25, 2023.

Conclusion

Building upon the significant milestones achieved up through the KORUS agreement, the past seventy years of the U.S.-Korea economic relationship have demonstrated the strength of the alliance across all sectors. From post-war reconstruction to the Asian Financial Crisis, and recent shifts in global geopolitics, the relationship has weathered many storms. Today, Korean brands are well established as household names in the United States, while the United States remains an essential trade partner for Korea. Continued partnership is necessary to address trade protectionism, supply chain vulnerabilities, and economic coercion. How the two countries continue to be partners will define what it means to be an economic ally in the twenty-first century. By continuing to work together to protect each other from the challenges brought by an increasingly multipolar world, the United States and Korea are poised to thrive together in the years ahead.

Tom Ramage is an Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from the official White House Flickr