The Peninsula

Disrupting Supply Chains: Evidence on the Japan-Korea Conflict

Published April 13, 2020

Category: South Korea

By Stephan Haggard and Jeongsoo Kim

The economic success of the Asia-Pacific has rested in no small measure on its finely-tuned supply chains. These global production networks are coming under stress from the COVID-19 crisis, but also from the new political economy of trade. The U.S.-China trade war has had as one of its stated objectives a “decoupling” from China, which of necessity means reducing American dependence on Chinese suppliers.

The history controversy that sparked the downward spiral in Japan-Korea relations threatens a similar eventuality. We now have interesting survey data from Korea on how these effects operate. The data suggest that uncertainty about even small amounts of trade in highly-specialized products can loom large for the businesses involved. Yet it also shows that governments and firms respond to these risks in ways that may harm firms in the sanctioning country.

The Japanese Controls

It is important to note that the measures undertaken by Japan did not take the form of outright export bans; rather, they involved a tightening of administrative procedures and the suggestion—or threat—that such controls could in fact be instituted. In July of 2019, the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry of Japan announced an “update of METI’s licensing policies and procedures on exports of controlled items to the Republic of Korea.” The update stated that Japan would restrict the export of Fluorinated Polyimide, Photoresist, Hydrogen Fluoride, and their related technologies by mandating an individual review for the three items (METI, July 1st, 2019). The three items share two similarities. First, they are critical materials for producing semiconductors and OLED screens, two crucial industries in South Korea. Second, the major Korean producers in this space–Samsung, SK Hynix, LG—have built complex supply chains that rely on these specialized inputs.

As a result of these measures, Japan effectively blocked export of liquid Hydrogen Fluoride for more than four months until it was finally approved in mid-November. Photoresist manufacturers were permitted to export in August for the first time, and Japan mitigated the export control on this product by moving from individual review to a special general bulk license in December. Japan resumed permissions to export Fluorinated Polyimide in September.

At the same time these new screening procedures were introduced, the METI also initiated “the public comments process for the amendment of the Cabinet Order removing the Republic of Korea from the Appended Table Ⅲ (so-called “white countries”) of the Export Trade Control Order” (METI, July 1st, 2019). After the public hearing period ended, Japan eventually removed South Korea from the white list and downgraded South Korea from a “preferred” to a non-preferred trade partner on August 2nd, 2019. As a result, Japanese exporters to South Korea no longer enjoyed a General Bulk Export License. Instead, they were required to seek permission from Japan’s export control authorities unless they acquired a Special General Bulk Export License, which requires more rigid standards than the General Bulk Export License.

In addition to the list control, Japanese authorities also could regulate any export and technology transfer to South Korea under a more general “catch-all” control when deemed necessary (METI, August 2nd, 2019). The potential magnitude of these controls—although not actually invoked–was particularly wide-ranging. According to Korean sources, total trade volume that potentially fell under the list and catch-all controls was about half of all Korean imports from Japan. Furthermore, among 4,898 items which were under the catch-all controls in 2018, 707 items were products in which Korea depended on Japan for more than 50% of imports of the product; Korea was completely dependent on Japan for 82 of these items.

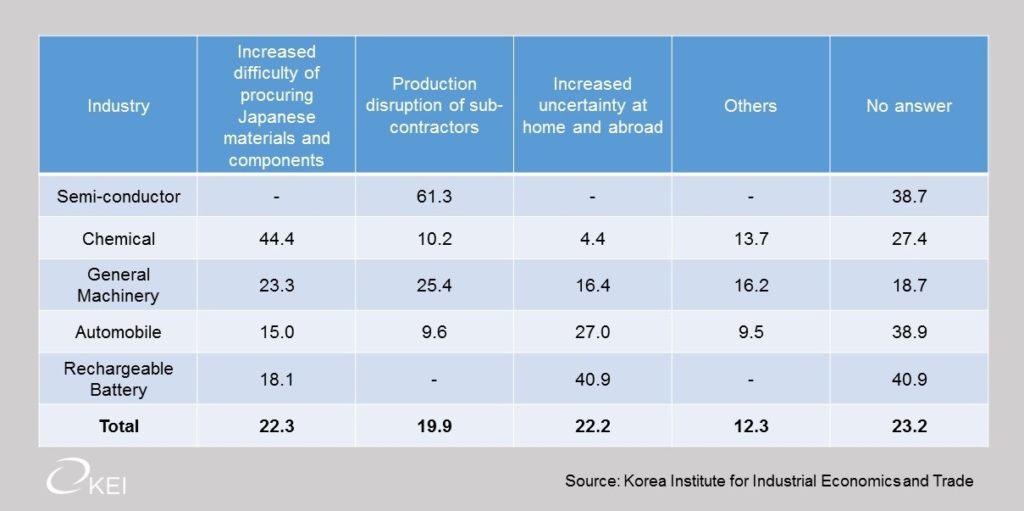

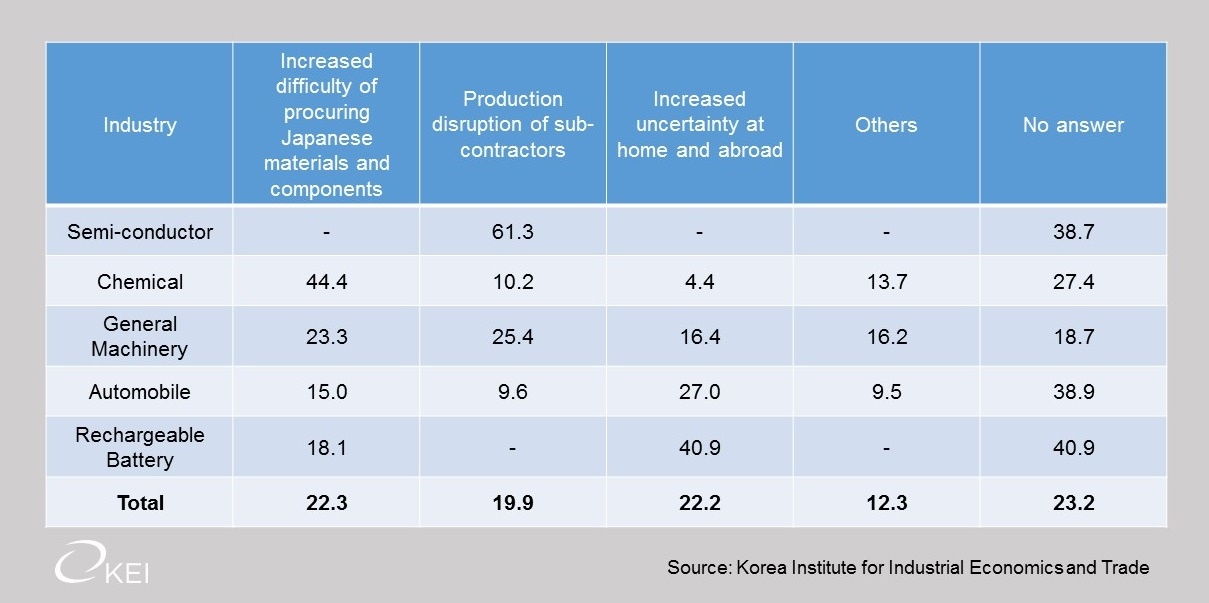

A survey conducted by the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics and Trade (KIET) in September 2019, asked 1,051 South Korean manufacturers about the effects of the measures, and nearly 80% said that they anticipated no effects or that they were even positive (no effect [77.8%], slightly positive [1.0%], very positive [0.4%]). Only 10.8% of manufacturers reported a slightly negative effect, with 3.5% answering they would experience strongly negative effects (민성환, 강두용 2019, 22).

Yet when we drill down into the most-affected industries, the picture changes. The table below looks in more detail at the five major industry classifications anticipating the most negative effects; the table also provides more detail on the particular problems they foresaw. Fully 60% of semi-conductor manufacturers polled foresaw production disruptions of sub-contractors, even though an analysis we conducted of the Korean semi-conductor sector showed no statistically significant change in profitability between the 3rd quarter of 2018 and the 3rd quarter of 2019. 44% of respondents from the chemical industry expected supply interruptions while the rechargeable battery industry showed a particularly high response rate with respect to “increased uncertainty.”

The Perverse Effects of Controls

It has long been known that sanctions are of necessity costly to the sanctioning country. And there is evidence in this regard for Japanese firms in these sectors as well. For example, during the first month of Japan’s new export measures, Japanese Hydrogen Fluoride producers suffered a sharp decline in their stock prices. The stock price of Morita Holdings Corporation was 1,942 JYP on July 1st; it fell to 1,552 JYP on August 12th. The price of Stella Chemifa dropped from 2,930 JYP on July 1st to 2,460 JYP on August 7th (Yahoo Finance), declines of 20.08 and 16.04 percent respectively.

Of greater long-run interest is the fact that South Korea did not take the restrictions lying down. The episode sparked a rethink of its reliance on Japan for intermediate inputs and components, new efforts to diversify sources of supply and even import-substitution measures. South Korea’s National Assembly passed a supplementary budget measure to support substituting for Japanese products on August 2nd, 2019. Nor were the sums trivial: 65 billion won ($54.15 million as of 1 March 2020) was allocated to technology development, 28 billion won ($30.86 million) for reliability tests, and 32 billion won ($35.28 million) for evaluation of mass production of critical intermediate inputs. The South Korean government also increased budget support related to material and components from 827 billion won ($911.96 million) in 2019 to 2.1 trillion Won ($2.315 billion) in 2020, and provided loans worth of 2.5 trillion Won ($2.75 billion) to support investing in foreign companies that have needed technologies (산업자원통상부 소재부품총괄과 2019, 3). In part as a result of these efforts, the Korean firm SoulBrain Co Ltd succeed in developing and producing Hydrogen Fluoride of “12-nine” purity (0.999999999999 pure). South Korea’s Minister of Trade, Industry, and Energy went so far as to publicly announce that South Korea no longer depends on Japanese Hydrogen Fluoride (Song 2020).

Nor were these effects limited to gains for Korean companies. DuPont, the U.S. based chemical firm, announced in January of 2020 that it decided to invest $28 million to build Photoresist production facilities in South Korea (The Korea Herald 2020).

Conclusion

As trade and foreign direct investment has slowed globally in the last three years, globalization has been dealt a further blow by the increasing politicization of global supply chains. Even putatively small administrative changes have highly disruptive effects on the industries in question, and precisely because of the specialization that such supply chains permit. Yet these measures also carry risks for the sanctioner that the U.S. needs to consider as it goes down a more nationalist route. Being an unreliable partner has costs as foreign governments and firms seek to reduce their risks.

Stephan Haggard is the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the University of California – San Diego. Jeongsoo Kim is a masters student at the School of Global Policy and Strategy, University of California, San Diego. He received his Bachelor’s Degree from the Republic of Korea Naval Academy. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone.

Photo from the Port of Tacoma’s photosream on flickr Creative Commons.