The Peninsula

Decoupling, De-risking, and South Korea’s Strategic Challenges

Since 2019, decoupling has been the keyword for the global economy. This trend mainly manifested around the US-China trade war, in which the two economies tried to reduce their economic dependency on each other. It had a tangible impact on global supply chains as multinational corporations shifted their production away from China. For instance, GoPro, the mobile camera maker, moved its US-bound production out of China to Mexico. Apple Inc. also shifted some of its production from China to India and Vietnam. South Korean companies were faced with a similar constraint, during which some considered “Vietnam as the next China” as part of a “China plus one” strategy, which gained some momentum as China’s zero-COVID policy continued.

De-risking: A Middle Ground

However, as one can imagine, this seemingly binary choice is not economically viable for many countries. President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen said in March 2023 that the European Union’s relationship with China should focus on de-risking through diplomacy. Since her speech, the word has become viral to the point that then President Joe Biden even said that “the US is for de-risking with China, not decoupling” in an address to the United Nations in September 2023. The address was perceived as an acknowledgment that the United States would not cut all ties with China. This should be good news for multinational corporations, as they can expect reduced risks associated with doing business in China.

The de-risking strategy also includes multilateral cooperation among allies. For instance, the trilateral summit between the United States, South Korea, and Japan at Camp David in August 2023 aimed to strengthen economic ties between the three countries. As an ongoing effort to reassure trade and economic security policies, consulate generals of the three countries have even hosted a seminar in Germany in November 2024 to discuss how trilateral initiatives can be extended with the European Union. However, the future of the trilateral relationship is uncertain, as President Biden, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio are all no longer in power.

Decoupling 2.0?

What will be the trend for the global economy under President Donald Trump’s second term? My best prediction is a possible return to decoupling, even at a larger scale, which I frame as “Decoupling 2.0.” Unlike the 2019 decoupling trend, recent evidence suggests that decoupling 2.0 is shaped around countries other than China.

Mexico and Canada, the two largest trading partners of the United States, have become central to President Trump’s second-term trade agenda. On February 1, 2025, the United States announced 25 percent tariffs on imports from both countries. However, the tariffs were suspended for 30 days after Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau struck a deal to enhance border patrol efforts on both sides. In contrast, no agreement was reached with China, resulting in the imposition of an additional 10 percent ad valorem tariff by the United States, to which China retaliated with equivalent measures.

In addition, President Trump has also warned about tariff threats against the European Union unless it relaxes cumbersome regulations and reduces attacks on US businesses. The most crucial quote from President Trump was, “My message to every business in the world is very simple: Come make your product in America, and we will give you among the lowest taxes of any nation on earth.” In this instance, tariff threats are mentioned to encourage investment in the United States.

Recent developments signal a potential shift toward a new form of global trade decoupling. This time, the United States has been the focal point of concern. If trading partners perceive the United States as an unpredictable actor, there is a growing risk that alliances could strengthen against it. Countries may increasingly decouple from the United States to mitigate risks, as evidenced by the European Union and advanced economies moving away from aligning with the United States’ interest rate policies, which is a significant shift in global macroeconomic coordination. Moreover, with countries less dependent on US exports than often assumed, trade patterns are beginning to realign, diverting away from the United States and reshaping the global economic order.

In contrast, Japan has recently become more visible as a US ally. The US-Japan free trade agreement in critical minerals has been in force since 2019. SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son has already appeared twice since November 2024 in President Trump’s press conferences, with the latest one in January 2025, which included the announcement of billions of dollars in pledges for the Stargate project. While details are still unknown, Son likely realized that US-bound investment announcements are welcomed in Trump’s second term.

These events indicate that the traditional US allies are not safeguarded from potential tariff threats or non-tariff barriers. It appears that only the countries that will invest in the United States or cut global corporate tax rates will be part of Team USA. However, it is still unclear how much investment is enough to satiate the United States’ demand. Under such developments, China could avoid another trade war with the United States as long as Chinese companies invest more in the United States and some type of deal can be made with Washington.

Implications for South Korea

Where does South Korea fit into this discussion? The country will not be safe from economic threats from the Trump administration if the US government investigates the country for currency manipulation based on the trade surplus. Recent data indicates that SK Hynix in Indiana and CJ Group in Oklahoma are the only large corporations that invested in the United States in 2024, which might not be enough to impress President Trump. To align with America-First policies under the new decoupling era, South Korean companies must make visible US-based investments. For example, while SK Hynix’s multi-billion-dollar investment in the United States is a significant step, it may lack the visibility of high-profile announcements like SoftBank’s. This relative lack of visibility could undermine South Korea’s efforts to strengthen economic ties with the United States.

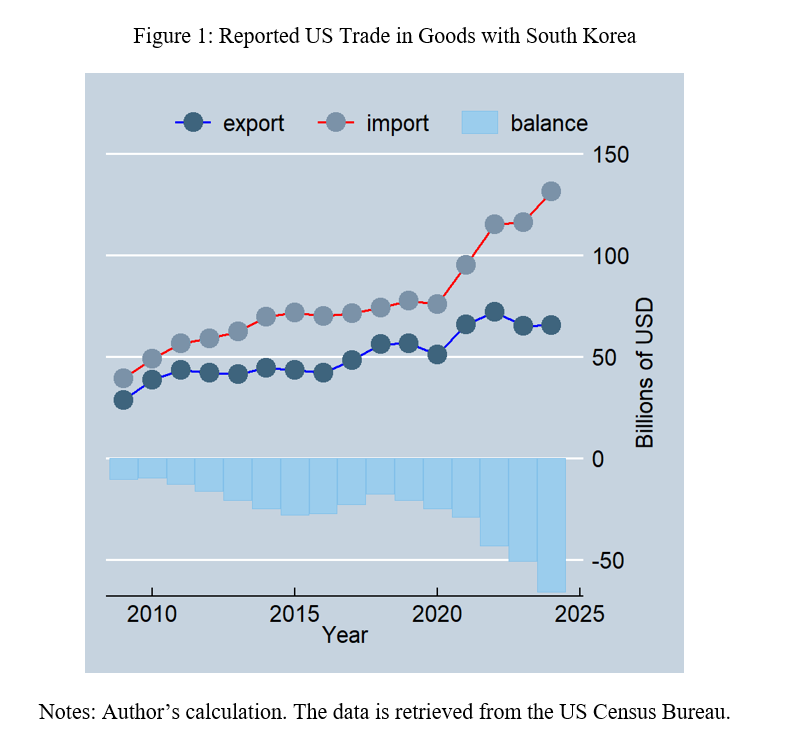

South Korea faces a growing risk due to its increasing trade surplus with the United States. According to data by the US Census Bureau, the United States imported 131.5 billion USD worth of goods from South Korea in 2024 while exporting only 65.5 billion USD, resulting in a 66 billion USD trade deficit—the largest in recent years. This imbalance could place South Korea in the spotlight as a potential target for US trade policy actions, especially as South Korea’s economic presence in the United States continues to expand. Notably, the data suggests that this trade gap has widened since 2020, a period marked by South Korea’s increased reliance on the US market.

However, this situation does not mean South Korea should consider decoupling from the United States, nor is a return to the 2019-era decoupling strategy viable. Instead, South Korea should embrace a de-risking strategy that requires a delicate balancing act. The past five years underscore the importance of this approach. De-risking includes increasing foreign direct investment in the United States to mitigate the risk of tariffs and demonstrate a commitment to the bilateral economic partnership. The growing presence of Korean firms in the United States is an encouraging sign in this regard.

To further address the trade imbalance, South Korea should focus on offsetting the US current account deficit by contributing to a financial account surplus through investments in US firms, equities, or other assets. This idea stems from the balance of payments (BOP) equation, which is BOP = current account + financial account + statistical discrepancy + official international reserves = 0. In this context, the US trade deficit appears as a negative entry in the current account. In contrast, a positive entry in the financial account reflects increased foreign-owned assets in the United States. Korean investors can actively enhance this positive financial account entry by purchasing US private assets, such as equities and other financial instruments. These investments not only support the US balance of payments but also strengthen South Korea’s financial ties with the United States, fostering opportunities for mutual economic benefits.

Conclusion

The trajectory of the global economy under President Trump’s second term appears to signal a shift toward “Decoupling 2.0.” Unlike the 2019 focus on reducing economic reliance on China, this new phase of decoupling emphasizes realigning trade and investment flows with an America-First agenda. While China may be able to stave off another trade war through strategic US-bound investments, traditional allies such as Mexico, Canada, and even the European Union face heightened risks of tariff threats and regulatory tensions. This evolving framework pressures countries like South Korea to adopt more visible US-based investment strategies to maintain favorable economic relations. Amid these developments, the future of multilateral cooperation, such as the trilateral ties among the United States, South Korea, and Japan, remains uncertain. Ultimately, the success of nations and corporations in navigating this turbulent landscape will hinge on their ability to adapt to the shifting rules of global trade and investment driven by this emerging decoupling paradigm.

Sunhyung Lee is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Feliciano School of Business, Montclair State University. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.