The Peninsula

Comparing Contexts: South Korea's Potential Nuclear Armament in the 1970s & 2020s

This piece is one of 12 contributions to KEI’s special project on South Korea’s nuclear armament debate that will run on The Peninsula blog over the next month. The project’s contributors include young, emerging, and mid-career voices, examining the debate from a historical, a domestic, and an international perspective. On Wednesday, March 15, KEI will host a conference featuring our various contributors’ work at our Washington, D.C. office and launch a compilation of all the pieces in a single, special KEI publication.

The 1970s was a turbulent period for the U.S.-ROK alliance. The Nixon Doctrine, America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, and detente with the Eastern Bloc exacerbated Seoul’s fear of U.S. abandonment. Ties with the United States were further frayed by the Park Chung-hee regime’s domestic oppression, which drew concerted criticism from the Congress.

In this context, Park yearned for a deterrent to North Korea independent of the U.S. security guarantee. In early 1972, Park secretly directed trusted officials to “secure the technology needed to produce nuclear weapons,” which are “necessary for keeping peace.”

In the summer of 1974, the CIA station in Seoul reported to Washington on the ROK government’s intent to pursue an independent nuclear deterrent. Following intense negotiations between 1974 and 1976, Washington successfully dissuaded Seoul from fully developing nuclear weapons, through a mix of security assurances, unilateral pressure, and coordination with Western allies. While South Korean interests in nuclear weapons persisted, South Korean leaders have made no serious effort to pursue them since.

The South Korean nuclear armament debate, however, has grown in 2023 as North Korea advances its nuclear weapons capability. A close examination of the U.S. government’s response to South Korea’s nuclear weapons program in the 1970s provides important implications for today’s discourse.

Global Non-Proliferation Regime

For Washington, South Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons was not only a peninsular issue, but also a problem for the global nonproliferation regime. The NPT came into effect in 1970 with strong support from the United States, which feared that domino proliferation could increase the risk of nuclear conflicts or accidental use. Washington was caught off guard by India’s first nuclear weapons test in 1974; wary of a potential nuclear arms race in South Asia, Washington and its Western allies imposed sanctions on India and suspended aid. Successive U.S. administrations had kept a close eye on potential proliferators such as Israel, Pakistan, and South Korea. The Park government’s pursuit of nuclear weapons thus came at a sensitive time when the United States was scrambling to salvage the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) through the “Nuclear Suppliers Group”—an initiative intended to regulate exports of sensitive nuclear technology.

In addition to engaging in bilateral negotiations with Seoul, American diplomats worked with their French and Canadian counterparts to stop South Korea’s nuclear program. The ROK had launched early negotiations with France and Canada to speed up the nuclear program without alerting Washington—including buying CANDU reactors from Canada for fissile materials, and reprocessing plants from France for plutonium separation from spent fuel. The United States pressured France, which initially viewed its transaction as a purely commercial issue, into slowing down the negotiation with Seoul. Canada, whose heavy water provision inadvertently helped India’s nuclear weapons program, was central in persuading Korea to cancel the reprocessing contract with the French.

In 2023, the United States continues to view non-proliferation on the Korean peninsula from a global rather than a bilateral perspective. Discussions in Washington surrounding South Korea’s potential nuclear armament often focus on the likelihood of a nuclear arms race in East Asia, by both non-nuclear states and existing nuclear powers. They also debate the implications of an East Asian arms race for the Middle East. Washington would likely impose all manner of costs upon Seoul if it tried to go nuclear because of its broader non-proliferation concerns.

Seoul might be tempted to present its case as a “Supreme Emergency” that requires drastic measures. ROK experts often mention Article X of the NPT which stipulates a right to withdraw if a signatory “decides that extraordinary events have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country.” However, Seoul would have to explain why America’s extended deterrence for Korea is significantly weaker than Washington’s security guarantees to other allies facing threats from China and Russia, which are not pursuing nuclear weapons.

Alliance Maintenance

In the 1970s, little trust existed between South Korea and the United States when it came to an issue as serious as nuclear weapons acquisition. Washington’s retaliatory suspension of the 1972 U.S.-ROK civil nuclear cooperation agreement and Export-Import Bank loan were connected to deteriorating sentiments in the U.S. toward security commitments abroad and the authoritarian Park regime. Washington was concerned that a nuclear-armed South Korea could act both independently and assertively against American wishes. For his part, Park faced a paradox, whereby drastic measures of a weaker client to respond to potential abandonment by the stronger ally inadvertently made it more likely. A mix of U.S. economic coercion and the existing South Korean fear of abandonment ultimately forced Park to cancel the French reprocessing deal and scrap the weapons program in its entirety.

Current South Korean advocates of nuclear armament assert that Seoul, a successful liberal democracy, should be trusted with nuclear weapons—ironically echoing North Korea’s own pledge to be a “responsible nuclear power.” However, many experts worry that the process of developing nuclear weapons could jeopardize the alliance, as South Korea could face staggering economic and political backlash. Moreover, in recent years, the United States and South Korea confronted substantial disagreements over key issues concerning China, North Korea, and Japan. Some Korean foreign policy experts questioned the tenability of the alliance in hypothetical settings where the strategic environment has vastly transformed, such as the signing of a peace treaty with North Korea. An environment where South Korea obtains nuclear weapons could profoundly impact Seoul’s perception of the U.S.-ROK alliance.

A nuclear-armed South Korea aspiring for strategic autonomy could behave like De Gaulle’s France after Paris acquired nuclear weapons in 1960 – defying alliance responsibilities for a more nationalist, independent foreign policy. A more strategically autonomous Korea resulting from nuclear armament might further complicate ROK-Japan relations. Given that the U.S.-Korea-Japan trilateral partnership is the crux of Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy, it is unclear if the alliance would survive the ROK’s nuclear weapons acquisition. Moreover, Seoul’s nuclear weapons development might significantly impact the wider U.S. alliance system in the region as it lacks the same multilateral architecture like NATO and EU in Europe.

Alternative Security Assurances

In the 1970s, Washington was initially puzzled by the seemingly paranoid Park regime. There was growing consensus in Washington that Seoul was “capable of maintaining reasonable defense posture against the North,” potentially even “without American ground combat troops.” North Korea’s Six-Year Plan (1971-1976) was a limited success, while the South’s economy gradually surpassed the North through its fast-growing heavy industry. Both China and the Soviet Union were unwilling to sponsor North Korean leader Kim Il-sung’s aggressions, as they were each preoccupied with mutual animosity and rapprochement with the United States. Many in Washington considered Park’s pursuit of nuclear weapons a gamble based on groundless fear of the North Korean threat and American abandonment.

The issue, however, was as much about perception as about reality. U.S. Ambassador to Korea Richard Sneider noted in his private archives that South Korea was “suffering the agony of self-doubt.”[1] This sentiment was particularly acute following South Vietnam’s collapse in 1975, abandonment of Taiwan, and ongoing North Korean provocations. South Korean leaders especially saw Washington’s transition from Saigon’s staunch ally to a third-party broker as a damning indictment of the U.S. reliability. ROK officials further saw America’s perceived prioritization of the alliance with Japan—which was researching nuclear power without a stern U.S. response—as evidence of potential U.S. abandonment. Sneider pointed out that Seoul harbored a “siege mentality” that psychologically normalized measures as drastic as a secret nuclear weapons program.

Sneider cautioned the Ford administration that an entirely heavy-handed approach to stop South Korea’s nuclear program would frighten Seoul. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who initially favored coercive pressure, was persuaded. Ensuing American efforts to thwart South Korea’s nuclear program included alternative security assurances. In 1975, Kissinger, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, and Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger each gave explicit defense commitments to Seoul, and transferred modern aircraft including the F-4, F-5, and A-37 to the ROK. The Ford administration emphatically stated that U.S. military forces in Korea would not be removed. The subsequent Carter administration reneged on this promise and vowed to withdraw American troops, but Seoul’s nuclear program was largely dismantled by then.

In 2023, many in the West are puzzled why Seoul is so skeptical of the U.S. extended deterrence commitment. In Europe, America’s NATO allies mostly trust the U.S. to uphold its Article V commitments for collective defense. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine did not significantly alter U.S. credibility because the Europeans believe an official military alliance with binding commitments creates a context completely different from Ukraine’s. The seemingly insurmountable economic and conventional military gap between the two Koreas, buttressed by a treaty guarantee by the most powerful country in the world, renders discussions of a South Korean independent nuclear arsenal absurd to some. Many foreign policy experts even in Korea point out that Washington is unlikely to bow to blackmail from North Korea—a minor pariah state—at the risk of destroying the credibility of American extended deterrence commitment to states facing even more powerful adversaries such as China and Russia.

However, just as in the 1970s, the nuclear discussion is as much about perception as it is about reality. Popular South Korean characterizations of Kim Jong-un depict the dictator as erratic, irrational, and reckless. Some in the security establishment fear he could gamble on a weakened U.S. security umbrella to achieve communist reunification by blackmailing Washington with ICBMs that can hit the American mainland. For the South Koreans, “would the U.S. trade Seattle for Seoul?” is a lingering question. Korean sensitivity to the perceived “Japanese favoritism” also remains to this day. Korean media across the political spectrum frequently point out that Washington permits Japan’s nuclear fuel reprocessing, while denying the same right to Korea. Beyond the nuclear realm, the general idea that Washington values its alliance with Japan more has been a constant theme in Seoul’s foreign policy discussions. Certain conservative elements fear Washington could draw a “new Acheson line” connecting Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines against China, while excluding South Korea. In the 1970s, America’s provision of conventional assistance to South Korea was enough to stop Seoul’s nuclear plan as the latter had little choice; in 2023, that may not be enough.

Transformed Regional Strategic Context

However, a transformed regional strategic context complicates the feasibility of providing alternative security assurances. Providing a concerned U.S. ally with conventional military assistance was relatively straightforward in the 1970s for two reasons.

First, the Sino-Soviet Split and U.S.-China Detente meant that China tolerated and even embraced the U.S. presence in the region. Conventional U.S. military assistance to South Korea did not irk Beijing, as China was more preoccupied with counterbalancing the Soviet Union. By the early and mid-1970s, a large-scale direct military conflict between China and the Soviet Union was a realistic possibility. Furthermore, China welcomed U.S. political and military presence in the region as a “bottlecap” on a potential resurgent Japanese militarism. The 1972 Japan-China Joint Communique, which normalized diplomatic relations between Tokyo and Beijing, went as far as to implicitly accept the 1969 Nixon-Sato Communique’s discussion of the alliance’s coverage of Taiwan. As Secretary of Defense Schlesinger assured South Korean leader Park Chung-hee himself in August 1975, Beijing viewed U.S. military assets in Asia as Washington’s leash on problematic U.S. allies, not a blank-check for their adventurism. Ironically, U.S.-China détente—the very context fueling Park’s fear of American abandonment—rendered Washington’s alternative security assurance to Korea both feasible and convenient.

Second, China was not only unwilling to sponsor North Korea’s provocations, but also tepid in protecting Pyongyang’s security interests. China was still recovering from the disastrous Great Leap Forward. Maoist fanatics during the Cultural Revolution criticized the North Korean leadership for being “revisionist.” Tensions at the China-North Korea border resulted in armed clashes in 1969 and 1970. North Korea sought to exploit the changing geopolitical circumstances, but to no avail. In 1975, Kim Il-sung visited China to win Mao’s support in renewing an offensive on the South while the U.S. was still grappling with the damage of Vietnam; Mao declined. With South Korea not strong enough to threaten China directly, and with no ostensible danger of losing North Korea as a buffer, Beijing held little concern over renewed U.S. security commitments to South Korea.

The strategic environment has now dramatically shifted. U.S.-China great power competition translates into vehement Chinese opposition to a strengthened U.S.-ROK alliance. American officials have hinted at an expanded role for U.S. Forces Korea beyond the peninsula, and South Korea faces greater pressures to do more in upholding the U.S.-led liberal international order. Meanwhile, China opposes the U.S.-led hub-and-spokes alliance system, calling it a “relic of the Cold War.” Any significant moves to enhance U.S. extended deterrence commitments in East Asia will likely be met by fierce retaliation from Beijing. Economic retaliations similar to during the THAAD row could be re-imposed; even worse, military pressure could be applied – which Kissinger noted is China’s traditional tactic on weaker neighbors to “teach them a lesson”.

Equally importantly, North Korea has become useful for China in its competition with the United States. Mutual distrust between China and North Korea runs deep, but their security interests are increasingly aligned in the face of what Beijing calls “U.S.-led encirclement.” Deterioration in broader U.S.-China relations over issues such as Taiwan and the South China Sea could provoke China into encouraging North Korean aggression. China prefers that U.S. military assets and political attention are fixed on North Korea, which might otherwise be deployed directly against China.

Conclusion

Seoul and Washington will have to communicate intensely to ensure that the nuclear debate does not undermine the alliance. Alternative security assurances from the U.S will be crucial, taking into account South Korea’s perception of the North Korean threat, American credibility, and alliance discrimination. Intensified U.S.-China competition and a strengthened China-North Korea alliance will continue to pose challenges. Just as the Vietnam War propelled ROK’s nuclear aspirations in the 1970s, failure to fend off North Korean aggression or Chinese revisionism in the region would radically dial up the nuclear debate.

Park Chung-hee decided to relinquish the nuclear program in hopes that the U.S. will “protect South Korea from any types of North Korean attacks”. When Jimmy Carter proposed to withdraw U.S. troops from Korea, Park allegedly regretted his decision to forgo the nuclear program. He, however, successfully betted on Washington’s security establishment to resist Carter’s agendas – solid institutionalization of the U.S. security guarantee ultimately saved the alliance. American commitment to ROK will have to be independent of DC politics, firmly rooted to shared values and interests.

Taehwa Hong is a MPhil candidate in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. His research focuses on Indo-Pacific security, U.S.-China competition and South Korean foreign policy. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

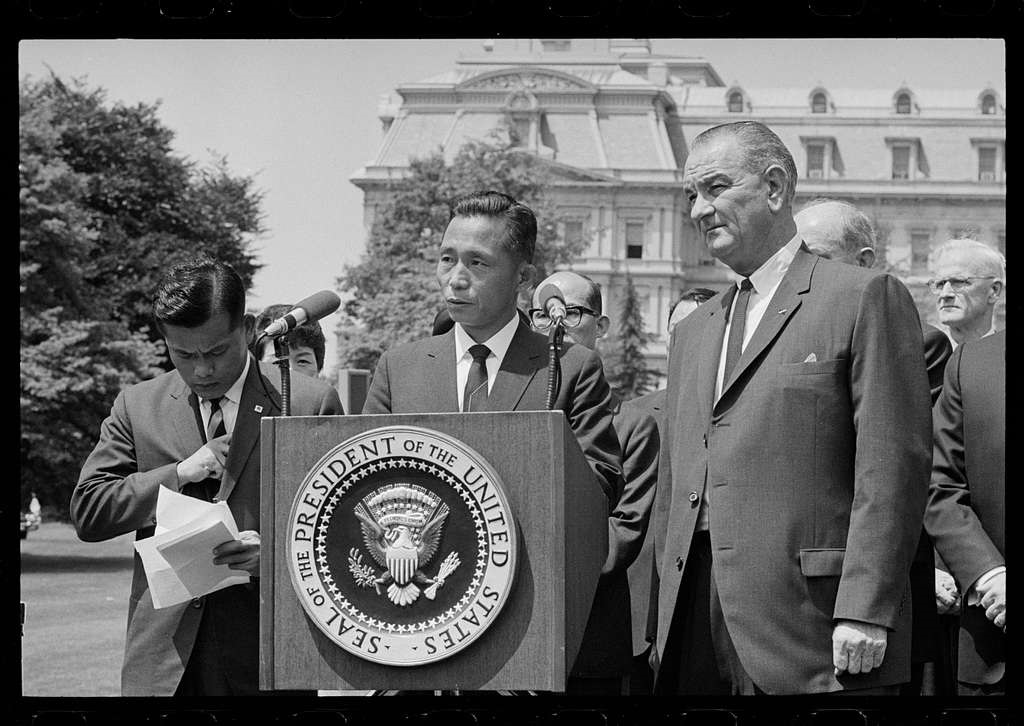

Photo from picryl.

[1] Generously provided by Daniel C. Sneider, Ambassador Richard Sneider’s son and a lecturer in international policy at Stanford’s Ford Dorsey Master’s in International Policy.