The Peninsula

China’s April Trade with North Korea—Are Sanctions Starting to Bite?

By William Brown

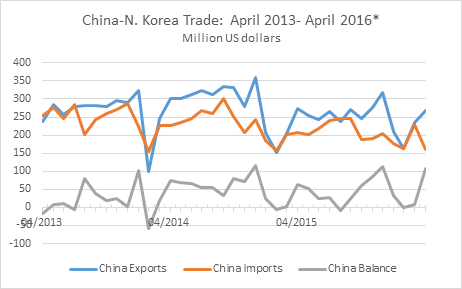

China’s Customs Bureau on Tuesday released its global trade report for April that includes details of the country’s trade with North Korea[i]. Some initial impact from UNSC sanctions may be observed, although seasonal changes tend to obscure the picture. Overall trade with North Korea was down about ten percent in April, from year-earlier levels, with Chinese exports down 1.5 percent and Chinese imports down 22 percent, the later due a decline in coal prices and volume. The data shows China maintains a small surplus although China Customs still mysteriously excludes crude oil shipments which very likely continue and which would add substantially to the recorded balance. If these shipments continue at past levels, which is likely, these would amount to about 50,000 tons of crude a month, or $15-$20 million[ii] at current prices.

*Global Trade Atlas, Excludes Chinese crude oil shipments

The UN Security Council ordered the new trade and financial sanctions on North Korea on March 2 (SCR 2270), so this April data is the first to give us a sense of how China is going to enforce the restrictions, imposed after Pyongyang snubbed multiple previous orders by the UNSC to stop nuclear and ballistic missile testing and exploding what it termed a hydrogen device on January 6. In addition to the long list of previous sanctions, these “toughest ever”–as described by numerous Western officials–additions prohibit purchases of North Korean coal and iron ore (except as such imports serve to further humanitarian or civilian employment needs), purchases of several other high-value North Korean minerals and metals (apparently without the obviously important civilian exception), and forbids sales to North Korea of various aviation fuels except to provision normal aviation service. New sanctions also are to be applied to a number of individuals and companies and require more intensive inspection of North Korean carriers and improved customs enforcement. As is normal with any country’s customs data, the specific entities doing the trading are not disclosed so this new data cannot tell us for certain whether China is actually adhering to its own rules.

Chinese Exports to North Korea

Chinese exports to North Korea amounted to $268 million in April, compared to $272 million in April 2015. Seasonal effects normally lower the trade in the early part of the year so comparison with February or March data means little. Year-to-date exports (January through April) were up about 5 percent with jumps in Chinese fertilizer and apples sales, and other consumer goods, offsetting declines in various machinery sales.

Aviation fuel sales to North Korea are the most specific new UNSC prohibition, presumably because kerosene type fuel is used in most North Korean rockets. China recorded only 527 tons of aviation kerosene (HC 27101911) shipments in April, probably mostly sold to North Korean aircraft operating through Beijing or other airports, as allowed by the new rules. But this was quite normal and points to some exaggerated notions expressed in the sanctions. Occasionally, over the years, as shown below, Beijing supplies a significant amount of such fuel, but normally North Korea produces its own needs, presumably at its Ponghua refinery, using crude oil supplied by China. There is nothing in the new sanctions that would prohibit this activity. Why China occasionally supplies this fuel, the last significant shipment was in March 2014, is not known to us but presumably it is for military use.

Chinese exports of other petroleum products continued as usual. These are mostly diesel fuel, fuel oil, and gasoline products.

Chinese Imports

The 22 percent decline brought Chinese imports in April down to $161 million compared to $202 million from North Korea a year-earlier. Year-to-date data shows much more stability—through April they were $730 million, down only 3 percent from the January through April period of 2015.

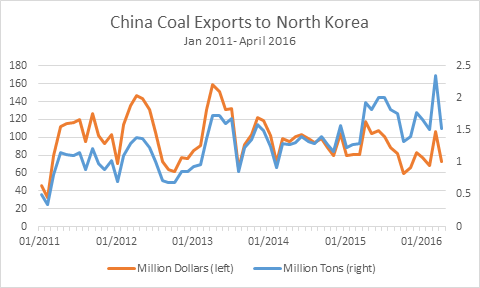

The April plunge came largely at the expense of North Korea’s coal industry, called out to be severely sanctioned by the UNSC. Chinese coal imports in April totaled $77 million, down 38 percent in value from April 2015 levels as prices fell 20 percent. Volume also declined by a steep 21 percent to 1.53 million tons from 1.9 million tons. The drop is impressive and could be read as an impact of sanctions but it came after a large uptick in March when traders may have anticipated the tougher Chinese rules. Year-to-date coal imports from North Korea actually rose in volume terms from January to April 2015. Moreover, weather may have had an impact; this North Korean anthracite is for household heating use, not for the steel industry. In fact, North Korea must import coking coal from China and elsewhere for its own steel industry.

Chinese iron ore imports are similarly sanctioned by the UNSC but have dropped steadily in recent years, earning North Korea only $5 million in April. Zinc imports rose to $7 million but, as with iron ore, Chinese imports of North Korean metals generally have fallen since 2011, with steep drops in prices. Most analyses of North Korea indicate that metals, and in particular, non-ferrous metals, are a core area of comparative advantage thus declines in this area bode poorly for economic development.

These declines in primary and secondary goods, however, have been more than made up for by surging imports of textiles and apparel from North Korea. In April Chinese apparel imports flattened after steep increases earlier in the year; year-to-date Chinese imports are still up 29 percent from January to April 2015.

“The Toughest Ever” Sanctions

One month of trade data will not tell the whole story but we can begin to see some impact, particularly with coal. For those who expected China’s trade with North Korea to abruptly fall off, the data will be disappointing. In fact, weaknesses in the sanctions regime are evident in this data, most clearly with respect to how China can choose to apply rules of origin to the coal and iron ore trade and evoke broad principles as to the need not to damage North Korea’s civilian economy. Anthracite coal and metals mining are large industries in North Korea and linking all or even most such production and sales to the military or to weapons industries is going to be hard to do. Moreover, an interesting spurt in growth in non-sanctioned but highly valuable zinc trade will be well worth watching. North Korea has among the world’s largest reserves of this high valued metal. On the other hand, where military units, or the several sanctioned trade companies that deal with coal and iron ore, are identified, there is little reason to expect China’s government will not try to enforce its own new rules. The key for everyone, not just China, will be to be able to carefully differentiate between private and government traders.

Similarly, with respect to sales to North Korea, Chinese firms struggling to keep factories humming as economic growth slows, naturally take advantage of demand for their products in North Korea and plenty of North Korean workers are willing to provide cheap goods and services to China in exchange. Many of these revenue earnings will not show up in trade data but a rough idea of how much they garner might be seen in the goods trade balance—China is not providing much investment to North Korea, so the North Korean deficit must be made up with cash flows of some kind. This trade, unlike trade managed by state-owned firms in both countries, and by military units in North Korea, is likely to help North Korea’s growing private sector and may be at odds with Kim’s desire, voiced at the Party Congress and at a subsequent factory visit, to exert more planning into the command economy system and to limit foreign trade by following an import substitution strategy of development.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Prince Roy’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[i] Global Trade Atlas, accessed x May, 2016.

[ii] [7.3 bbl/t *$45/bbl *600,000= $197,000]