The Peninsula

A National Security Strategy of Retreat Leaves Asia to Manage the Consequences

The Donald Trump administration’s much-awaited National Security Strategy (NSS) landed last week with an audible thud.

The somewhat truncated document is an odd combination of social media-style triumphalism and an effort to lay a strategic veneer on the administration’s often chaotic and contradictory policies. But the document clearly expresses an America-First view of the world, a combination of isolationism and U.S. primacy that places allies and partners near the bottom of the priority list.

Much of the strategy’s attention is on the assault against Europe and the dismissal of both the NATO alliance and European unity in favor of supporting right-wing ethno-nationalism. In homage to the nineteenth century, U.S. control of the Western Hemisphere—in the name of a “Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine—has regional priority.

But in Asia, the NSS offers a strange marriage of two historical moments, both still controversial.

One is the infamous Acheson Line, a reference to the speech delivered by then Secretary of State Dean Acheson in January 1950, drawing a U.S. defense line along the island chain from Alaska through Japan to the Philippines, notably excluding the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan. It was a declaration that many believe convinced Stalin to give the green light to Kim Il Sung to invade South Korea, igniting the Korean War.

Trump’s NSS describes a new Acheson Line, the so-called First Island Chain, presented as the first line of defense in the Pacific. Bizarrely, it contains no mention of either North Korea and its nuclear arsenal or even the Korean Peninsula.

This is combined with a revival of President Richard Nixon’s equally infamous Guam Doctrine. Amid the waning days of the Vietnam War, Nixon told reporters during a 1969 tour of Asia that while the region was important to the United States when it came to military defense, “the United States is going to encourage and has a right to expect that this problem will be handled by, and responsibility for it taken by, the Asian nations themselves.” One product of this doctrine was the withdrawal of the 7th Infantry Division from South Korea, a decision that shook confidence in the U.S. security commitment.

The message of this NSS echoes Nixon’s. It demands not only vastly increased defense spending from South Korea and Japan, as well as other partners such as Taiwan and Australia, but also that they assume the roles the United States currently plays in defending regional security, now defined as the First Island Chain. Their own defense gets no mention. As the NSS puts it: “Given President Trump’s insistence on increased burden-sharing from Japan and South Korea, we must urge these countries to increase defense spending, with a focus on the capabilities—including new capabilities—necessary to deter adversaries and protect the First Island Chain.”

The NSS makes it clear that the United States will stand aside and ask its allies to take on the task of defending the Pacific and Europe. “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over,” the document pronounces. The United States will now ask “allies to assume primary responsibility for their regions,” while presumably still beholden to the United States’ whims and desires.

As Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth stated last week, Trump prefers “countries that help themselves…rather than dependencies.” Those that spend more are “model allies”—for now, South Korea is on that list, but Japan is not—but “allies that do not, allies that still fail to do their part for collective defense, will face consequences.” It was not explicitly stated, but the withdrawal of U.S. security guarantees appears to be on the table.

The Retreat from Values and Strategic Competition

The two previous national security strategies, one issued during the first Trump administration and one by the Joe Biden administration, were shaped around the concept of strategic competition with China and Russia. The new document almost completely abandons this driving idea.

Instead, “it prioritizes threats from the Western Hemisphere, European civilizational decline and overregulation, and trade deficits but says nothing about the Russian threat to U.S. interests and views China almost entirely through the lens of economic security,” argued Thomas Wright, a former national security official under the Biden administration.

Evans Revere, a former principal deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, offered this scathing summary of the NSS.

“This is not so much a national security strategy document as it is a screed telling America’s allies, partners, friends, and adversaries that the United States they once knew is gone. Gone are the priorities, principles, beliefs, and assumptions that underpinned U.S. strategy and diplomacy for most of the past 80 years during both Democratic and Republican administrations. Gone is the belief in a U.S.-centric international economic and security order based on American predominance, power, alliances, and defense commitments. And gone is the belief, once deeply shared across every previous U.S. administration, that America’s destiny was to promote a core set of values, including democracy, freedom, and equity, in cooperation with like-minded allies and partners.”

Media in South Korea and Japan echoed these concerns. “Trump administration formalizes strategy of isolationism based on US interests,” headlined a commentary in the progressive Hankyoreh. The editor of a major Japanese paper told this author that he took the NSS “as another statement of America in retreat” that “reconfirms that the entirety of US national core interest is defined as commercial benefit.”

The editor argued that the Trump administration appears to believe that “authoritarianism can be acceptable in the name of sovereignty, and effective foreign policy is conducted only by strong leadership” or “strongmen” like presidents Trump, Xi Jinping, and Vladimir Putin.

“America’s abandoning of its self-position as a leader of free world is obvious in this NSS,” the Japanese editor opined.

The China Question

Some have taken solace in the fact that while the NSS prioritizes the homeland and the Western Hemisphere, it does give some length to discussing China. There are elements of traditional approaches and policy continuity, particularly an embrace of military deterrence and a reaffirmation of support for the status quo in the Taiwan Strait.

But the entire section on China is focused on economic and commercial relations, with the clear suggestion that the two countries can reach a more equitable division of the global economy and presumably the spoils of commerce.

“We will rebalance America’s economic relationship with China, prioritizing reciprocity and fairness to restore American economic independence,” says the NSS. “Trade with China should be balanced and focused on non-sensitive factors.”

“The Trump admin believes in the possibility of a mutually advantageous economic relationship with China,” wrote Michael Sobolik, a senior fellow at conservative Hudson Institute, on December 5.

Trump’s NSS makes no mention of the war against Ukraine or China’s support for Russian aggression, much less China’s military and nuclear buildup. Not only does North Korea drop out of the national security policy, but the entire goal of denuclearization is also gone, perhaps reflecting a growing acceptance of North Korea as a nuclear state.

Even though Taiwan occupies a link on the First Island Chain, the focus is almost entirely on preserving its role in the electronics supply chain. “Asia is important because of its growing GDPs, and Taiwan must be defended for semiconductors and sea lanes,” wrote the veteran Japanese newspaper editor.

Two recent developments seem to manifest this view of Asia. One has been Trump’s apparent decision to effectively ignore China’s increasingly aggressive—including military confrontations in the skies—response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s remarks about the potential impact of a crisis over Taiwan on Japan’s security. Indeed, the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal both reported that Trump, after talking to Xi, may have urged Takaichi to back off.

Perhaps more importantly, Trump has cleared the way for a dramatic easing of export controls on the sale of high-powered Nvidia semiconductors to China, effectively putting commerce over security. Ironically, perhaps the NSS also calls for allies like South Korea and Japan to prioritize trade with the United States over China.

“In Europe, we are afraid that Donald Trump’s America may be selling us out to Russia,” wrote former Economist editor Bill Emmott. “In Japan, where I have just been, the fear is of Trump selling them out to China.”

Daniel C. Sneider is a non-resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America and a lecturer in East Asian Studies at Stanford University. All views are the author’s alone.

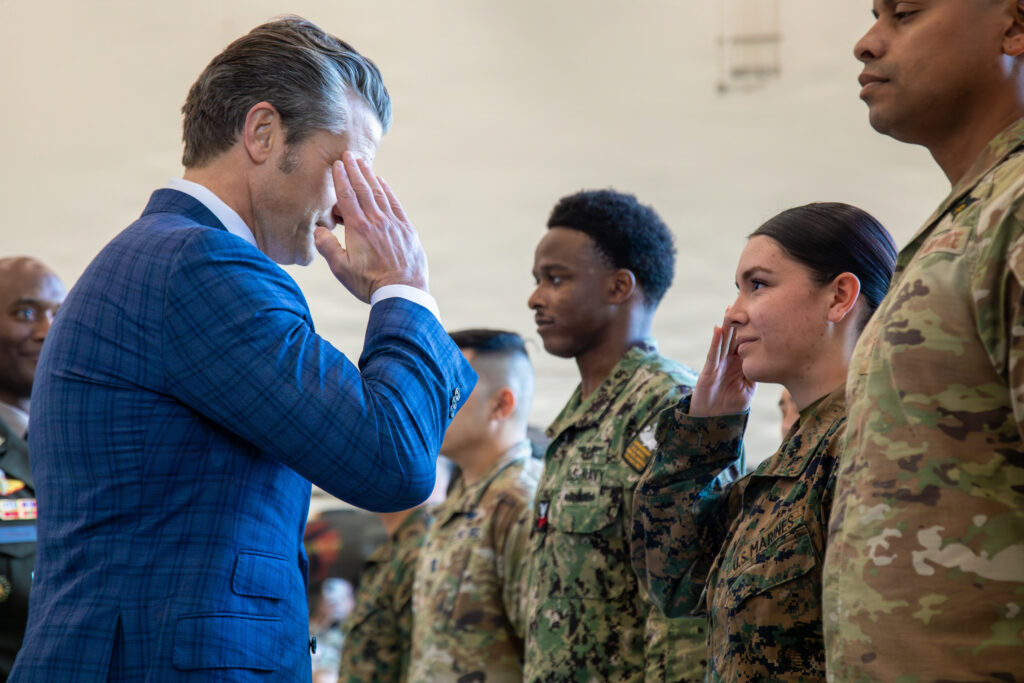

Feature image from DVIDS.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.