The Peninsula

[2024 in Review] North Korea’s Economy: It’s All About Money

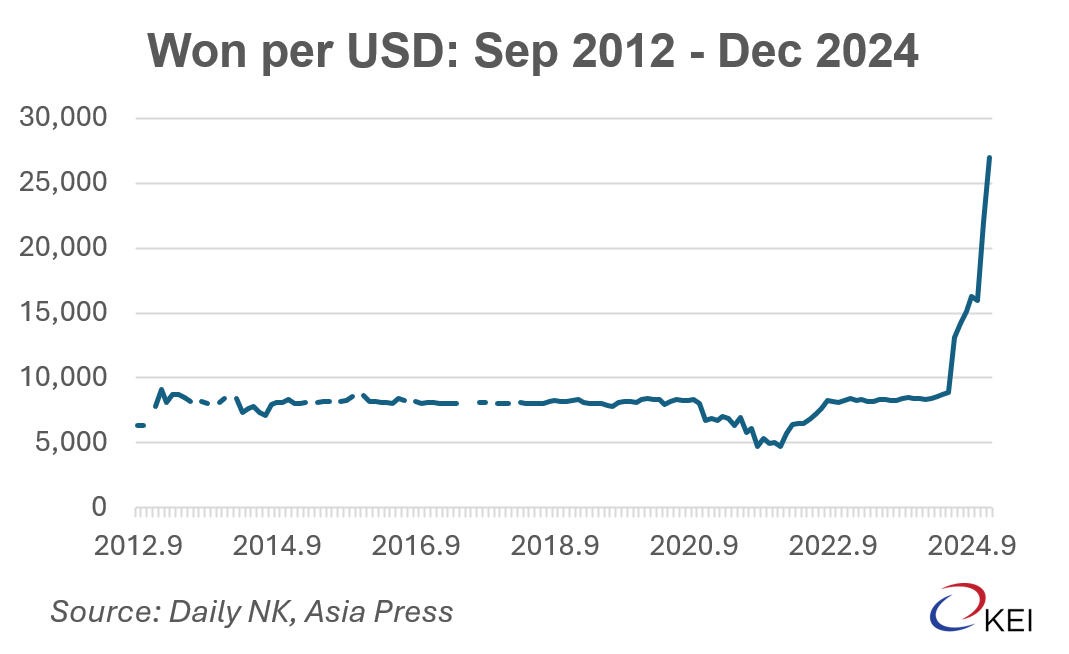

Financial issues plagued North Korea in 2024 with Kim Jong Un’s singular success, halting the hyperinflation and currency debasement, suddenly coming unraveled in mid-year. After a decade of price and currency stability, the value of the North Korean won suddenly fell by about two-thirds between July and December. By year’s end, 27,000 won was needed to buy a single US dollar, up from 8,000 won, the steady average of the past decade.

Similar devaluation occurred against China’s yuan in the country’s unusual partially dollarized economy where the three currencies circulate together. Dollarization helped stabilize the won as it forced the regime to be very conservative in printing new cash or in extending credit, much like Hong Kong’s currency board system, but that in turn crippled the ability of monetary authorities to drive the economy And it gave citizens a sound vehicle for savings, which have likely soared, again lowering inflationary pressures and giving citizens some protection against the state. US cash in one’s wallet does that. Once trust in the local currency begins to fall, however, there is no policy break to control it and for a time a spiral effect dominates, bringing it down further. Interest rates, a capitalist tool, normally rise, encouraging holding the currency but these are still frowned upon in communist societies. In private markets even in North Korea they cannot be avoided and speculation, with big winners and losers, skyrockets.

Over his tenure, Kim’s success with financial stabilization has come at a big cost to economic growth as lack of domestic credit in the increasingly monetized economy has pushed down investment spending, usually the driver of growth in communist economies.

It is unclear what happened this year to force Pyongyang to relax and print money and extend credit. With little ability to control foreign currency, the won value plummeted as citizens sold won and bought dollars and yuan. Added to that was a gradual reopening of the border with China and a large influx of Chinese products while North Korean exports remained stymied, creating a huge trade deficit and an outflow of dollars and yuan making them more valuable.

The drop in won value caused a jump in basic food prices, and anything imported from China. Even mostly homegrown rice jumped from about 5,000 won per kilogram to 9,200 by year end. Corn prices rose proportionally as did fuels. Enough data on general prices is lacking so a CPI cannot be constructed—the South Korean Bank of Korea will attempt that later in the year—but it is clear inflation has returned after a decade of unusual stability.

The devaluation is not without positive attributes and in fact was likely caused by a needed boost in static state sector wages which had fallen to near nothing—millions of state workers are paid mostly in fixed rations in the old socialist system and these have not kept up with private sector earnings. The dual economy—one state, one private—with vastly different relative prices and wages retards development and breeds corruption as everyone wants to arbitrate the differences.

Reports from defectors indicate many classes of workers began to see increases in their nominal wages. A unified economy where these wages were close to private earnings would greatly increase productivity and economic growth although it could be devastating to the regime which depends on the controls implicit in a rationed economy. And, already, the jump in market prices is frustrating the state workers even with their big increases.

Kim is likely searching for a way out of the monetary mess, and North Korea’s end of year meetings and speeches focused on the economy and economic plan may offer hints on his policy direction. Income from tighter Russia-North Korea ties can help but is likely insufficient and temporary. A better solution, but with ideological implications and thus highly unlikely without a change in leadership, would be for the state to sell off some of its holdings of land, and capital stock, using the money to pay for salary increases, while decentralizing the uncommonly unproductive state system. This would be akin to following China’s model of development. In the meantime, a boost in exports, difficult in the sanction’s environment, would help but would require a reversal of Kim’s recent self-reliance strategy.

William B. Brown is interim Senior Advisor at the Korea Economic Institute of America and the principal of Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, Advisory LLC (NAEIA.com). The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.