The Peninsula

South Korea Faces Policy Bind as GDP Contracts

Published February 13, 2026

Author: William Brown

Category: Economic Security, Economics, Indo-Pacific

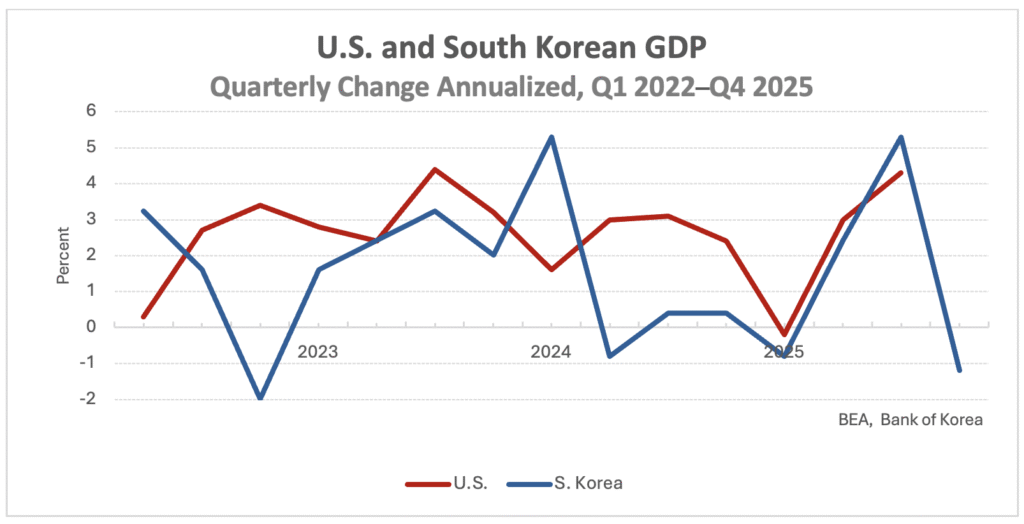

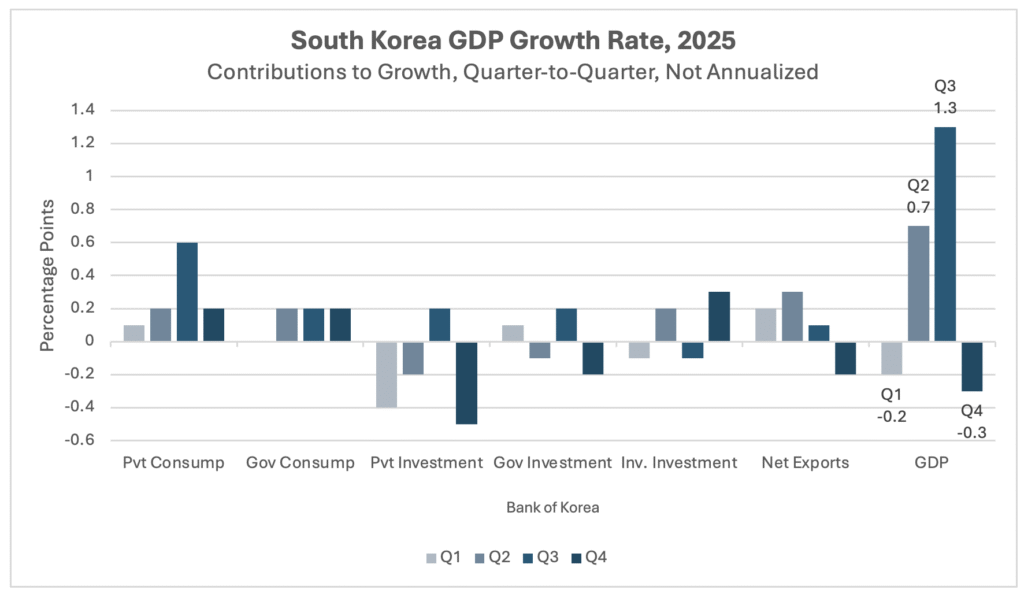

South Korea’s GDP declined 0.3 percent in the fourth quarter, a surprising result after earlier expectations of 0.1 percent growth. Buoyed by a strong third quarter, Bank of Korea (BOK) data shows that GDP was still 1.5 percent above fourth quarter growth in 2024. On a seasonally adjusted annualized basis—a measure familiar to American audiences—and which best characterizes current conditions, GDP fell at about an annualized rate of 1.2 percent.

BOK data shows that full-year 2025 GDP rose 1 percent above 2024, about as expected, but it nonetheless dampened expectations that the surge in the third quarter might lead to a sustained upturn. The rate for both the quarter and the year was the lowest since the pandemic.

Despite the weak production results, Korea’s central bank has chosen to hold its interest rates steady, afraid that a decline in rates, which is needed to induce faltering investment, would further harm the weak won. The weak won, on the other hand, is helping drive net exports.

Korea had grown in sync with the United States for most of 2024, but apparently diverged in the fourth quarter. U.S. data is delayed until February 20, but early indications suggest about 4 percent annualized growth. In the Indo-Pacific, Japan’s growth is similarly slow, while Taiwan—Korea’s semiconductor rival—is booming.

One bright spot is a 0.8 percent, or 3 percent seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR), rise in gross domestic income (GDI), measuring national output from the income side of the national accounts. This is likely related to a stimulus program the Korean government launched last summer, though such transfer payments are not included in GDP calculations. Relative terms of trade (a rise in prices of the country’s exports relative to its imports) might have also helped. The rise in income cushions the blow to corporate profits sustained during the last quarter of 2024, though it comes at a cost to the country’s rising fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio.

Commentators emphasize that Korea’s Q4 GDP drop reflected a pullback from the unusually strong third quarter performance stretched by stimulative government policy and heavy public investments. Strong demand for healthcare drove both public and private consumption in the fourth quarter, each adding 0.2 percentage points to growth. But the data shows continuing trouble in the investment sector, especially construction, which knocked off 0.5 percent of GDP growth for the quarter. Other fixed investments, both public and private, also declined after the third quarter boosts. Inventory investment climbed, adding 0.3 percentage points, but warehoused goods may subtract from future growth. Net exports declined as exports fell more than imports.

The surprise decline in the current account creates a dilemma for the BOK and the Lee Jae Myung administration as they try to strengthen the won. Lee hopes the won will return to 1,400 to the dollar, where it sat in Q1 2025. It was getting close to 1,500 just before the 4Q 2025 GDP release, but that would likely require higher interest rates or reduced stimulus to gain investor confidence in the won. But monetary and fiscal policy present trade-offs. Lowering interest rates could weaken the won and raise import costs, while increased stimulus spending risks pushing the deficit even higher. Interest rates were cut last year and now sit well below U.S. rates. And stimulus spending has already pushed the fiscal deficit above 3 percent of GDP—the level the OECD considers near an upper bound—though it remains much lower than the U.S. deficit-to-GDP ratio.

Despite the slight decline in net exports in Q4, Korea ran a large current account surplus of USD 50.4 billion in 2025, with exports boosted by the AI revolution and the cheap won. But the trade surplus is offset by a capital account outflow, as Korean export earnings are invested abroad, like a saver putting their money in a faraway bank. These investments, plus the BOK’s large foreign exchange reserves, were built up over time and are now contributing to a strong interest income and profit flow of dollars to Korean owners, thus raising incomes even as they depress domestic production. This is exactly what has happened to Japan over the past several decades.

Turning the Ship

One way Seoul may try to improve GDP growth in 2026 is by inducing more investment from abroad. This might seem to contrast with U.S. policy, which is requiring an increase in the opposite direction (more direct investments from Korea into the United States), which by itself could exacerbate the weak won. But both could happen at the same time. The foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into the United States will likely reduce the buildup of official Korean U.S. dollar reserves, held mostly in low-interest Treasury assets, making Korean-owned assets more profitable. In fact, this was exactly one of the solutions Stephen Miran, member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, originally suggested as a multilateral approach to dollar adjustment as part of what he called a potential “Mar-A-Lago Accord.”

Well-designed and competitive cross-country direct investments should raise productivity in both economies. The defense industry and related technologies are promising sectors, where Korea could welcome U.S. investments in Korean companies just as Korean companies invest to build ships and other products in the United States. Policies in both countries might have to change to allow this, but these should be welcomed by both sides. U.S. travel and tourism investments in Korea could also pay off well, as overseas tourists are increasingly seeing Korea as a prime destination.

William B. Brown is the principal of Northeast Asia Economics and Intelligence, Advisory LLC (NAEIA.com) and Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Feature image from The Blue House.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.