The Peninsula

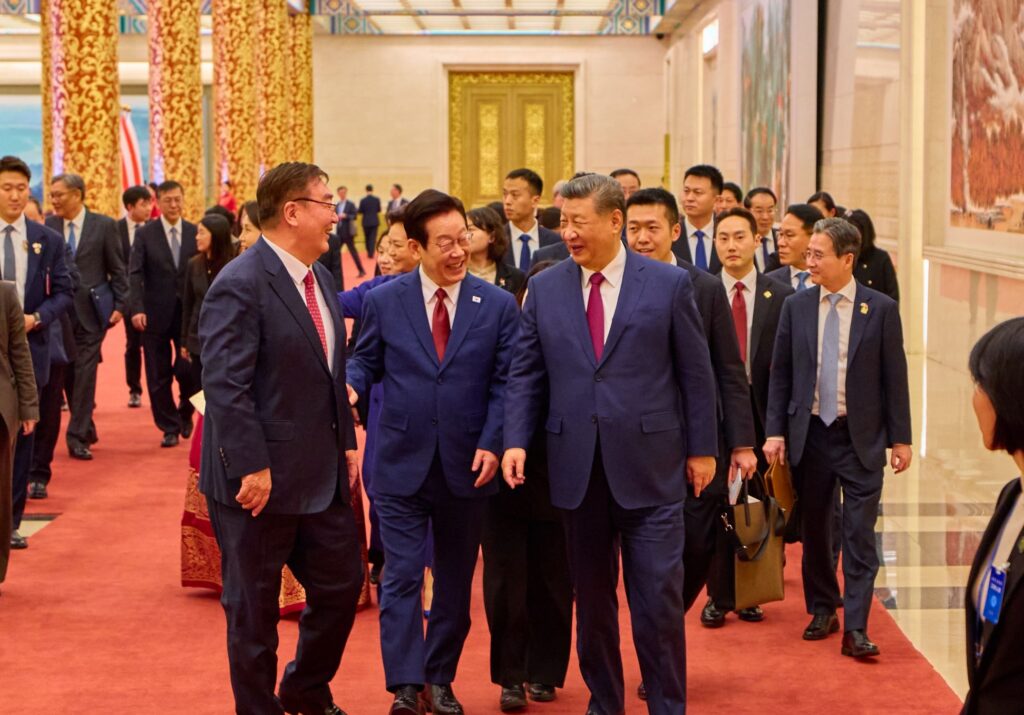

Where Korea-China Ties Are Heading Following the Lee-Xi Summit

The summit between South Korean President Lee Jae Myung and Chinese President Xi Jinping reinforced the mostly stable and improved direction of bilateral relations under the new Korean president—but left unresolved some issues related to political economy. The Korea-China summit came on the heels of some substantial economic actions by China and occurred under the shadow of longer-term ones. The Chinese government had recently sanctioned—then released—Korean company Hanwha’s shipbuilding subsidiaries for aiding the United States. Korea’s advanced manufacturing companies have faced similar treatment as of late, when China placed and then suspended export controls on critical minerals critical for Korean semiconductors, batteries, and other high-tech products. Last, since Korea’s 2016 deployment of the U.S. THAAD missile defense battery, China has maintained an unofficial “Hallyu ban“ on Korean cultural products.

These would have been highly sensitive issues to consider as Korea strove to make diplomatic inroads with China (its largest total trading partner). However, any agreement with China carried the risk of alienating the United States, as the Korean government sought ways to cooperate with China on trade and security policy. Meanwhile, the ongoing diplomatic row between China and Japan likely gave the Chinese government a major reason to make overtures toward Korea to discourage it from taking a definitive side in the political conflict.

Ultimately, Lee and Xi signed fifteen memorandums of understanding (MOUs) and “cooperation documents” covering science, technology, transportation, and trade, in addition to the accompanying business deals and MOUs focusing on export promotion, content development, and technology partnership signed by members of the large Korean business delegation that accompanied President Lee during his visit. Notably, both countries agreed to conclude negotiations on the investment and services tranche of a full Korea-China Free Trade Agreement (FTA) within the year. This will likely do the most to institutionalize the diplomatic progress made at the summit and provide tangible progress on bilateral engagement. The full implementation of an FTA covering these areas has been stalled for the last decade.

But the absence of an official joint statement, along with China’s continued enforcement of the Hallyu ban, may mean that the meeting marked the start of negotiations rather than its end. Seoul may have to wait for negotiations between Washington and Beijing on tariffs and sanctions to be finalized before pursuing further progress with Beijing in areas ranging across technology, investment, and trade. At the same time, China faces a delicate balance with its relations with Korea, Japan, and the United States amidst massive shifts in global trade policy. With President Lee’s vocal affirmation that the longstanding policy framework of “China for economy, U.S. for security” is no longer tenable, time will tell just how this new Korea-China relationship will take shape.

The original version of this piece was published in “The Northeast Asia Digest: Ask an Expert” Series of the National Defense University Institute for National Security Studies (INSS).

Tom Ramage is Economic Policy Analyst at the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI). The views expressed are the author’s alone.

Feature image from The Blue House.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.