The Peninsula

Ensuring Long-Run Fiscal Sustainability in South Korea

Published December 11, 2025

Author: Randall S. Jones

Category: Economics, Indo-Pacific, Economic Security

Ensuring Long-Run Fiscal Sustainability in South Korea

South Korea’s fiscal position remains stronger than most advanced economies, but the foundation beneath that stability faces significant challenges. Years of disciplined budgeting kept public debt low and enabled the government to maintain steady surpluses throughout the 2010s, even as social spending expanded. Korea now faces a more challenging outlook, shaped by rapid population aging, slower economic growth, and a declining labor force. While the fiscal trajectory still appears manageable, Korea faces widening long-term risks, especially in the absence of a durable framework to guide policy as demographic pressures intensify.

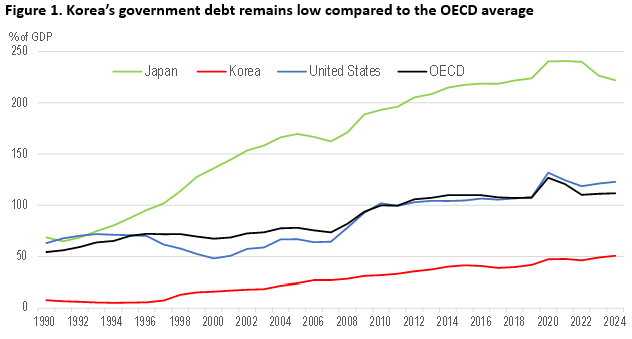

Between 1990 and 2024, the Korean government’s gross debt rose gradually from 8 percent of GDP to around 50 percent (Figure 1). It remains far below the OECD average of 110 percent and the United States at 122 percent. Korea’s relatively sound fiscal position reflects its focus on balanced budgets—until recently—and its relatively young population, which has limited public spending on health, long-term care, and pensions.

Note: General government debt in gross terms. OECD estimates in 2024 for Korea, Japan, and the OECD average. Source: General government debt | OECD.

Despite rising public social spending, Korea’s fiscal balance was consistently in surplus until the pandemic

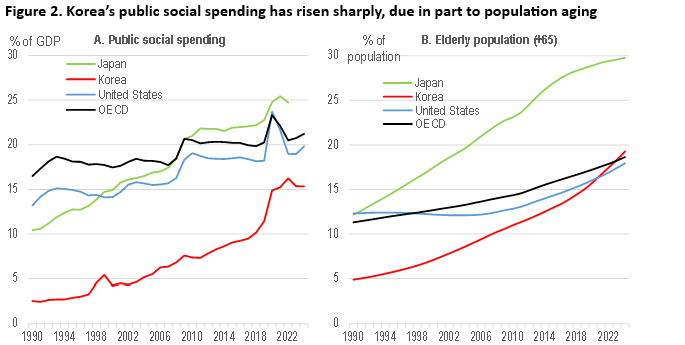

Korea’s government expenditure increased significantly from around 14 percent of GDP in 1990 to 37 percent in 2023 (on a general government basis). As in other high-income countries, rising public social spending has accounted for much of the upward trend in government outlays in Korea. Indeed, it grew from 2.5 percent of GDP in 1990 to more than 15 percent by 2023 (Figure 2, Panel A). The increase was the largest in the OECD after Japan and was much greater than the OECD’s average four percentage-point rise.

Rising public social spending was driven to a significant degree by population aging. The share of Korea’s population aged sixty-five and above rose from 7 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2023 (Panel B), more than double the average increase of 7 percentage points across the OECD.

Source: Panel A; OECD Data Explorer • Social expenditure aggregates; and Panel B; Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) | Data.

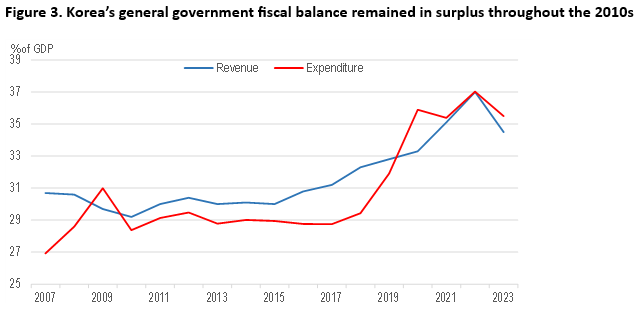

Nevertheless, the government budget remained in surplus between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 3). However, in 2020, a 13.4 percent hike in outlays to support demand and reduce poverty during the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant budget deficit (2.6 percent of GDP). In 2022, the government proposed a fiscal rule that would limit the “managed fiscal deficit” (i.e., excluding social security, which remains in surplus) to 3 percent of GDP to promote fiscal sustainability and curb the rise in government debt.

The deficit limit would drop to 2 percent if government debt exceeded 60 percent of GDP. The proposed rule includes an escape clause that allows authorities to respond to major shocks. However, the National Assembly never approved the proposed fiscal target.

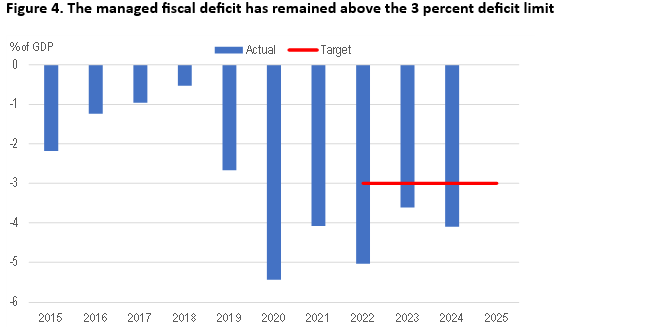

Korea’s overall fiscal balance has remained in deficit since 2020 (Figure 3). In addition, the managed fiscal deficit has stayed above the 3 percent limit since the fiscal rule was proposed, surpassing 4 percent of GDP in 2024 (Figure 4). Although the government previously committed to abide by the fiscal rule in 2025, the managed fiscal deficit is likely to be even higher this year. During the first three quarters of 2025, the managed fiscal deficit rose to KRW 102.4 trillion, the largest recorded for the January–September period since 2020. Total government spending is projected to rise by more than 10 percent in 2025, boosted by two supplementary budgets.

Note: The managed fiscal deficit excludes social security, which remains in surplus due to Korea’s immature pension system, which is still accumulating funds. The government proposed the 3 percent deficit limit in 2022. Source: Economic Bulletin, November 2025 – KDI – Korea Development Institute – RESEARCH – Periodicals – Economic Bulletin.

The 2026 budget, announced last August, contains an 8.1 percent increase in spending that reflects the Lee Jae Myung administration’s objective of using public investment as a catalyst to revitalize the economy. Innovation and technological leadership, particularly in AI, are key priorities. Government research and development (R&D) expenditures are expected to rise by 19.3 percent in 2026, while industrial policy spending will increase by 14.7 percent. The government has launched an AI master plan that includes thirty flagship projects in robotics, smart factories, and semiconductor development.

Rapid population aging will push up public social spending

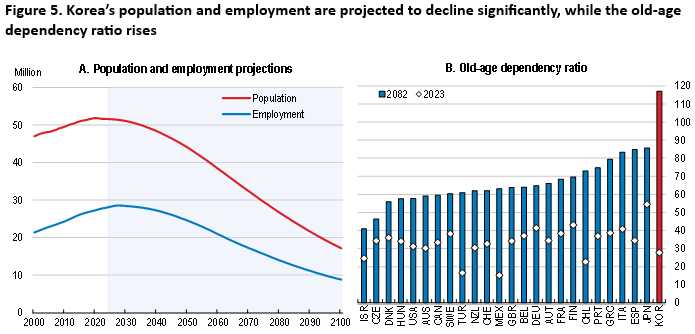

Korea’s population and labor force are projected to decline by roughly two-thirds by the end of the century, assuming that the total fertility rate (around 0.7), net immigration inflows (30,000 per year), and employment rates by gender and five-year age cohorts remain at their current levels (Figure 5, Panel A).

The shrinking population will also be considerably older. Currently, Korea’s old-age dependency ratio (the number of individuals aged sixty-five and over per person aged twenty to sixty-four) is below the OECD average at 28 percent, implying 3.6 working-age individuals per person aged sixty-five and over (Panel B). Korea’s ratio is projected to rise to 117 percent in 2082 (0.85 working-age individuals per person aged sixty-five and over), even assuming that the fertility rate converges to 1.85.

Note: Panel A assumes that employment rates by age group, the total fertility rate (around 0.7), and net immigration inflows (30,000 per year) remain constant at current levels. Panel B assumes that the total fertility rate in all countries eventually converges to 1.85 children per woman, a medium-variant forecast from the United Nations’ World Population Prospects. The old-age dependency ratio is defined as the ratio of individuals aged sixty-five and over to those aged twenty to sixty-four. Source: OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2024 | OECD.

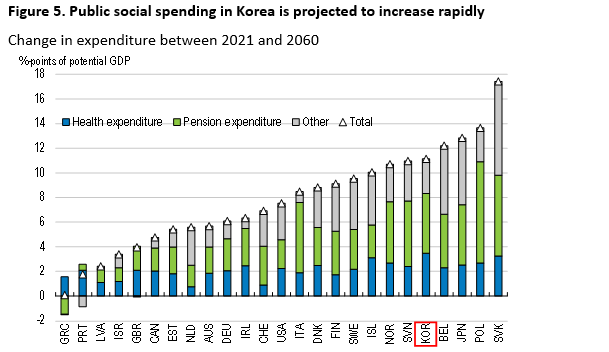

Public social spending is projected to increase by 11 percentage points of GDP between 2021 and 2060, boosting the total to approximately 26 percent of GDP. Pensions and healthcare will account for about three-quarters of the increase. Healthcare spending, including insurance payments and patient co-payments, for persons aged sixty-five and older increased by 39 percent between 2020 and 2024 and now accounts for nearly half of healthcare spending in Korea. Consequently, aging puts long-term fiscal sustainability at risk.

Improving Korea’s fiscal framework

Korea needs an improved fiscal framework to better align short-term fiscal policy with long-term aging challenges. Adherence to the proposed rule of limiting the managed fiscal deficit to 3 percent of GDP would strengthen Korea’s public finances considerably in the long term. The OECD’s Spending Better Framework includes setting fiscal rules and objectives, producing medium-term fiscal forecasts based on objective economic assumptions, preparing multi-year expenditure baselines (usually three to five years), and adopting top-down expenditure ceilings. The fiscal framework will need to include new sources of revenue in the long run to finance the costs associated with population aging. One key source of additional revenue should be an increase in the value-added tax, which is currently set at 10 percent, about half of the OECD average.

Randall S. Jones is Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from the South Korean Presidential Office.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.