The Peninsula

Digital Technology Traps for South Korea’s Trade Policy

Military historians often apply a superlative phrase to describe famous generals, stating that they are able to “snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.” This line of thought can be inverted as an apt description of policy stumbles—“we have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.” The South Korean government may risk this fate by following its skillful trade negotiation with the United States with a needless bruising fight over digital technology policy.

Comparing the costs of national trade adjustment has become a vital indicator of policy performance in the chaotic reset of the world economy forced by President Donald Trump. By this metric, Korea did remarkably well in its trade deal with the United States. Despite recent political turmoil at home, President Lee Jae Myung and his administration successfully negotiated a trade package that was less onerous than many had predicted. Neither Korea nor Japan was thrilled by the new U.S. baseline tariff of 15 percent and a required commitment to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in the United States. But Korea, despite being a smaller economy, secured a tariff deal similar to that of Japan (albeit Korea retains a 25 percent tariff on auto and auto part imports until the terms of its investment fund are finalized). Just as importantly, although nothing is certain with the United States these days, the terms for Japan’s future investments in the United States appear likely to be worse than those for Korea.

Yet, stumbling blocks over digital policy could sink Korea’s policy momentum. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) intends to pursue its objections to digital policies in Korea and other countries. U.S. digital firms have challenged Korea’s significant emulation of the European Union’s competition policy framework for digital platforms and regulatory safety policies for AI. They also question Korea’s restrictions on exporting geographic mapping data, its cloud security provisions that depart from international practices (apparently to shelter Korean firms), and technical standards for AI that are unique to Korea.

While USTR’s specific priorities remain uncertain, we can ask whether some of these policies could be modestly tweaked to avoid disputes and whether others advance Korean interests sufficiently to warrant a likely trade clash.

Can some Korean policies achieve their most important goals, but be adjusted on the margins to avoid a trade dispute? The answer requires distinguishing between the formal policy and the policy as it will be implemented. As every policy veteran knows, implementation determines much of the practical meaning of policy.

Korean digital platform firms, not American, dominate its domestic digital markets. Korea’s current competition policy partly arose from specific objections to the conduct of Korean firms, but its formal terms allow for discrimination against foreign platform firms. A pledge to introduce safeguards against such discrimination during the implementation process might largely resolve U.S. concerns. Similarly, if Korea implemented its AI policy in a manner similar to Japan (which also drew inspiration from the European Union’s AI policy), it would increase the role of firms sufficiently to better align practical choices in AI markets with lofty policy goals. Allowing U.S. firms to participate fully in the advisory process could further alleviate tensions.

A second question is whether some Korean policies advance international economic interests sufficiently to risk a trade quarrel. Some policies do not seem to do so. Indeed, it seems Korea has forgotten the policy strategy that helped propel its surging position in global digital markets.

Korea was a skilled manufacturer of desktop computers, memory chips, and other lower-value-added segments of the global digital market around 2000. The introduction of 3G mobile technology in the early 2000s created the first technical architecture for mobile phone technology that was digitally friendly. This ultimately enabled the rise of smartphones. Korea then made a smart gamble to move up the value chain. It chose to focus on a global standard, implementing 3G Code-Division Multiple Access (CDMA), which had major customers and government support in the United States. This was a clever strategy because the existing industry leaders in Europe and Japan had primarily geared themselves to implementing a rival 3G standard. This meant that the incumbent global leaders were not as well-positioned to compete with Korean firms for CDMA markets. Korean firms later chose to double down on using global standards by choosing Android for their own mobile phones. Growth in mobile phones further complemented and enhanced Korea’s position in the semiconductor industry. In contrast to the Korean strategy, China tried to rely on a homegrown, third-implementing standard for 3G that largely failed in the global marketplace.

Today, the Indo-Pacific region is a high-growth market for all versions of advanced digital technology. Investments in data centers for cloud computing and AI are growing faster than in Europe. Regional trade in digital services is expanding quickly. Specialized AI models, not the massive AI models of Google or OpenAI, are emerging across the region to perform specific applications that complement the region’s digital ecosystem. Yet, during my recent visit to Korea for APEC meetings on digital policy, I heard Korean startup entrepreneurs complain that Korea was requiring the use of unique Korean technical standards for AI ventures. If these startups hope to expand outside of Korea, they would have to support two sets of standards, a burdensome requirement that imposes product complexity and expensive engineering.

Perhaps there are some benefits for Korea from idiosyncratic national standards. But, recalling the CDMA story, how smart is it for Korea to gear a national digital policy around practices that are not prevailing globally, or even in its regional backyard? And it is precisely these kinds of issues around technical standards that have often fueled trade disputes with the United States.

Korea has the skills, world-class firms, and capital to be a major player in the emerging generation of digital technology. Embedding itself as a leader in the dynamic regional market by fitting into standardized technical practices can support its global strategy. It will also reduce the likelihood of new trade disputes with the United States that could undermine its trade agreement. It is time for Korea’s leadership to remember the risk of inadvertently snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Peter Cowhey is Dean Emeritus and Qualcomm Chair Emeritus at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy.

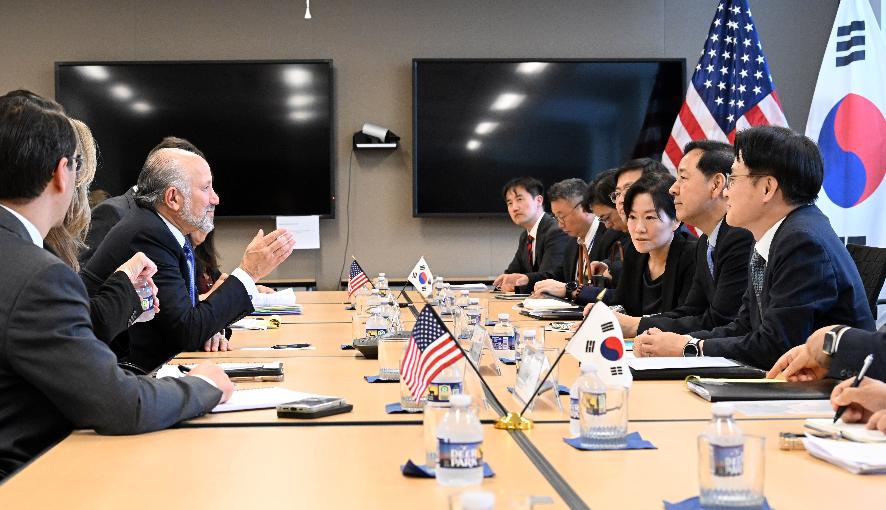

Feautre image from South Korea’s Ministry of Economy and Finance.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.