The Peninsula

U.S. Trade Deals, Letters, and Tariffs: Implications for South Korea

On July 7, President Donald Trump effectively delayed the 25-percent reciprocal tariffs against South Korea to August 1. The extension grants more time to reach an agreement but does not alleviate the need for a trade deal to achieve certainty and lower tariffs. Section 232 tariffs have remained in force during the pause of reciprocal tariffs, impacting several of South Korean exports. Trump’s letter to South Korean President Lee Jae Myung, published this week, reiterates the United States’ objectives and leverage, but may also indicate a motivation to strike a deal by providing more time for negotiations. So far, only the United Kingdom and Vietnam have reached deals with the United States, offering some insights. South Korea has much to offer the United States—advanced manufacturing, major energy imports, and a demonstrated willingness to invest in U.S. reindustrialization. With the original ninety-day pause expiring and the August extension in place, it is timely to assess the implications of recent developments for South Korea.

Universal, Reciprocal, and Industry Tariffs

President Trump has made tariffs a cornerstone of his larger political agenda. They have become a tool that the White House relies on to incentivize reshoring and reindustrialization of the United States, increase government revenue to help finance tax reforms in the recently approved Big Beautiful Bill, and persuade other countries to adopt and implement policies.

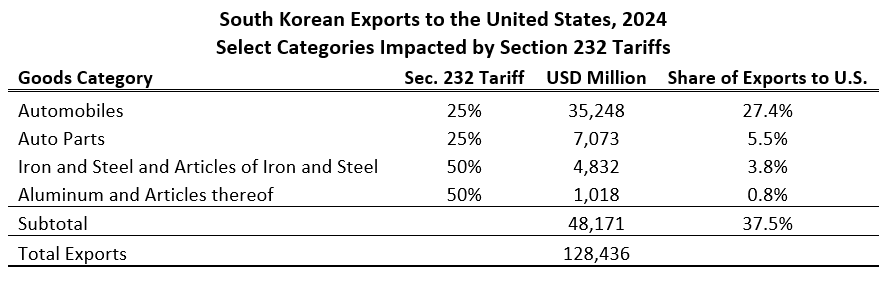

Tariffs announced since the administration took office that impact South Korea can largely be classified into three categories: 1) universal tariffs effectively setting a 10 percent tariff floor to any nation; 2) reciprocal tariffs against countries with large goods trade surpluses with the United States (25 percent in the case of South Korea); and 3) tariffs targeting specific industries, including automobiles and auto parts, steel, and aluminum as outlined in the table below. Trump has also initiated an investigation to add Section 232 tariffs on semiconductor imports and threatened to do the same against smartphones. Out of the three, only reciprocal tariffs have been on pause and—in the case of South Korea—remain paused until August 1.

While a 10-percent universal tariff applies to all nations, Section 232 tariffs affect a greater portion of exports from South Korea than from many other countries. In 2024, select key industries impacted by Section 232 tariffs represented almost 40 percent of South Korean exports to the United States.

Note: Iron and Steel and Articles of Iron and Steel line is an aggregate of HS codes 72 and 73. Sources | International Trade Centre, the White House, the White House

UK and Vietnam Trade Deals

The U.S.-UK Economic Prosperity Deal was the first to be announced following the Liberation Day tariff announcements on April 2. It was presented against a backdrop of previous negotiations between the two nations, formally launched in 2020. Notably, the United Kingdom maintains a goods trade deficit with the United States and faced no reciprocal tariffs ahead of the agreement. The deal did not affect general tariff levels, which remained at the universal tariff level of 10 percent. Rather, the deal declared an intent to improve market access in select industries.

On the one hand, the United Kingdom offered improved market access for agricultural goods, including ethanol and beef products. It addressed rules in areas of procurement, customs procedures, intellectual property rights, labor, the environment, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals. The United States, in return, promised to exempt the first 100,000 British automobiles from Section 232 tariffs, effectively applying the 10 percent universal tariff rates, and created a trading union for steel and aluminum, promising to negotiate “an alternative arrangement to Section 232 tariffs” relying on tariff-rate quotas.

Meanwhile, the preliminary deal with Vietnam represents a substantially different agreement. Rather than specific areas of improved market access, Vietnam promised to completely eliminate all tariffs against the United States, while the United States would lower its reciprocal tariffs against Vietnam from 46 to 20 percent. An important aspect of the deal is the 40 percent tariff levied on transshipments of Chinese goods through Vietnam. The deal will “establish favorable rules of origin” but leaves uncertain exactly how this provision would be defined and enforced.

The agreement seems largely in line with U.S. Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick’s vision for a trade deal with Vietnam. During questioning by Senator John Kennedy (R-LA) on June 4, Lutnick rejected a hypothetical U.S.-Vietnam trade deal with reciprocal zero percent tariffs. Instead, the secretary seemed inclined to a deal that restricts Chinese imports to Vietnam, taking aim at transshipments.

Letter to South Korea

On July 7, President Trump shared a letter addressed to South Korean President Lee, with similar letters to several other national leaders. In it, he invited Seoul to seek balanced and fair trade, in place of the “far from Reciprocal” trade relationship caused by tariffs, regulations, and non-tariff barriers. This is despite recent research from the Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI) estimating that South Korea charged the United States an effective overall tariff rate of between 0.19 and 2.87 percent in 2024. According to the letter, South Korean exports to the United States will face a tariff rate of 25 percent starting August 1, and transshipments will be levied higher tariffs according to their origin.

The letter does not mention rules of origin or how transshipments will be defined and determined. With the exception of transshipments, the letter effectively extends the pause of 25 percent reciprocal tariffs against South Korean goods. A day later, Trump added that “no extensions [beyond August 1] will be granted.”

Implications

So, what are some of the implications for South Korea?

First, the August 1 extension grants more time to reach an agreement but does not alleviate tariffs against the most important South Korean exports to the United States. The letter reiterates U.S. leverage and pressure on South Korea to reach a deal and reduce the burden of tariffs against its exports to the United States. It could indicate a U.S. motivation to reach a trade deal with South Korea without letting the higher reciprocal tariffs take effect.

Second, limiting transshipments of Chinese goods through U.S. trade partners is a priority for the Trump administration. This is indicated by the letter to President Lee, the trade deal with Vietnam, and Secretary Lutnick’s testimony. Considering that China is the largest trading partner of South Korea, and that important supply chains, including semiconductors, are closely interlinked, transshipments and rules of origin could become a contentious issue in trade negotiations between the United States and South Korea.

Third, universal and reciprocal tariffs are unlikely to be removed. However, the Vietnam deal would suggest that there is some room to lower but perhaps not completely eliminate reciprocal tariffs.

Finally, the UK deal included several industries that are also relevant to the U.S.-South Korea trading relationship. The Office of the United States Trade Representative’s 2025 National Trade Estimate Report highlighted access to the South Korean beef market—which was also included in the UK deal—as an area for possible improvements of non-tariff barriers. It also puts automobiles on the negotiation table, although the UK auto industry is more concentrated in the luxury segment than the South Korean producers, thus competing less directly with U.S. manufacturing, as highlighted by President Trump. The deal was also limited to 100,000 cars, a small number compared to the 1.43 million vehicles shipped from South Korea to the United States in 2024. A deal that includes significantly improved South Korean access to the U.S. automobile market could undermine Trump’s objective to industrialize the United States. Similarly, the intent to form a steel trading union between the United States and the United Kingdom seems more aimed at keeping cheap steel out of both countries rather than allowing British steel to compete with U.S. steel.

That being said, South Korea has lots to offer the United States as it is a leading manufacturer of ships and specialized semiconductors, demonstrates a willingness to make investments and contribute to U.S. reindustrialization, and imports large amounts of energy.

In short, the extended deadline for negotiations provides more time to reach a deal that can improve trade between the United States and South Korea. Both existing trade deals and the deep integration of U.S.-South Korean economic relations indicate some possible avenues, although other negotiations suggest that there are significant challenges ahead.

Nils Wollesen Osterberg is Economic Policy Associate at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Feature image courtesy of The White House.

KEI is registered under the FARA as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the government of the Republic of Korea. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.