The Peninsula

The Challenges of a Second Minimum Wage Increase in South Korea

Published August 15, 2018

Category: South Korea

By Suyeon Ham

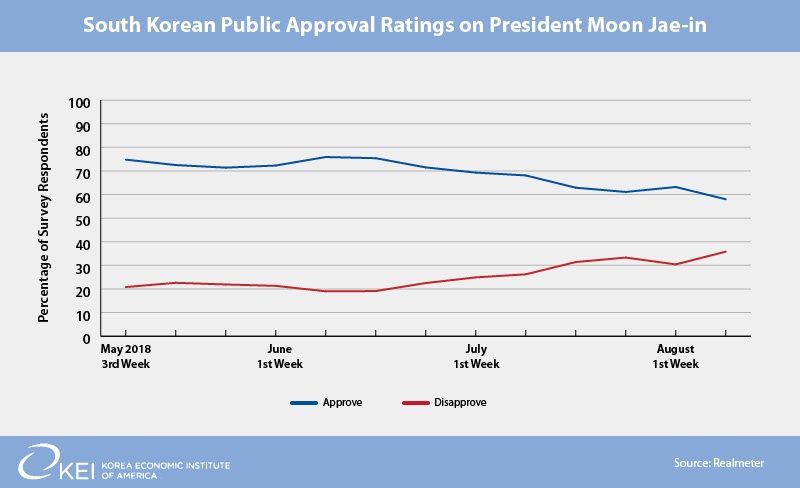

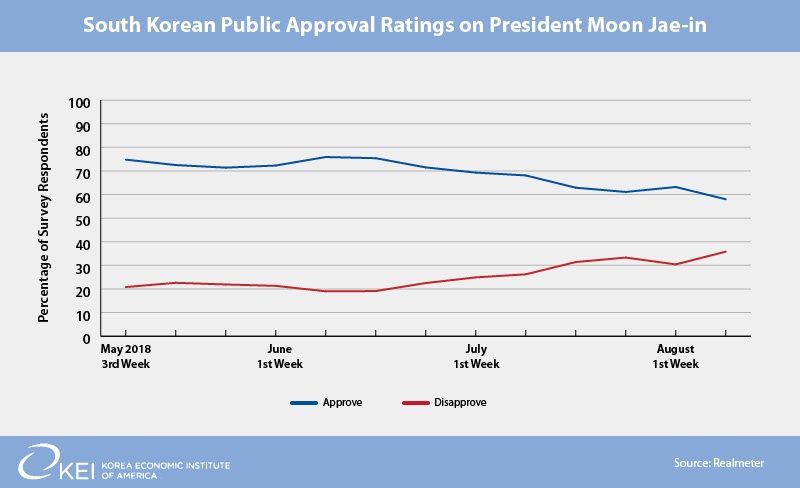

The South Korea government announced on July 14 that it will raise the minimum wage next year by 10.9% to 8350 won ($7.40), following a 16.9% increase this year. President Moon Jae-in’s drive to increase the minimum wage is splitting his supporter base, while at the same time casting doubt on his economic policies. As a result of the minimum wage issue, Moon’s approval rating fell 6 percentage points to 61.7 percent, which is the biggest drop since he took power last year.

On July 16, President Moon Jae-in apologized for an apparent inability to fulfill his key pledge, increasing the hourly minimum wage to over 10,000 won. To hit Moon’s target of 10,000 won by 2020, next year’s figure must be increased by 15.3 percent, according to calculations, but this is impossible to achieve. At the meeting, Moon apologized, saying that the Minimum Wage Commission’s decision makes it difficult to hit the target, but that he accepts the decision. At the same time, he promised that the government will draw up measures to prevent small businesses and self-employed people from being impacted, not only through employment subsidies but also through commercial property lease protection, reasonable credit card fees, and protecting franchises.

However, there is a growing backlash against the minimum wage hike despite Moon’s apology. The Korea Federation of Micro Enterprise said in a statement that merchants under the body will declare a self-moratorium on the state-set minimum wage and instead pay a rate based on separate wage agreements between employers and employees. Experts have warned that many small merchants will not be able to afford the minimum wage. As a result of the rapid increase, the monthly wage for a person who works 40 hours a week will go up from 1.57 million won this year to 1.74 million next year. An analysis by the federation showed that the average income of self-employed last year was 2.09 million won. The federation predicted that the average income of self-employed will fall below two million won due to the hike. Employment data has been worsening since the minimum wage was raised last year. The number of precarious workers — those hired temporarily or on a daily basis — fell by 247,000 in a year.

The situation is worse in the convenience store industry where only shopkeepers and employees suffer from the sharp minimum wage hike. The system will not greatly impact on the corporations that own the convenience store brands. However, it will directly influence the shopkeepers and the employees under both management and personal financial shortage. Now not only has the moratorium declared, but also the shopkeepers and their families have to work for themselves to lower labor costs. There are also increasing number of convenience store giving up late-night operation and an expectation that many convenience stores will shut down in the near future. The convenience store industry is especially sensitive to the minimum wage issue because the stores have low operating profits and high labor costs due to long operation hours. The revenue structure of convenience stores is highly dependent on rent, franchise loyalty fees, credit card fees, and labor costs. As the owner cannot control rent, merchant commissions and credit card fees, they have no choice but to reduce labor costs to raise revenue as raising prices has not been a viable option. Of course, the minimum wage hike is not the only reason for the depression in the industry today. For instance, analysts point out the fundamental problem stems from the excessive growth in the number of stores in the local CVS convenience store chain. Last year, the number of CVSs in Korea grew 12.9 percent from a year earlier to reach 36,823, while the revenue for each store increased by 0.2 percent during the same period. However, the minimum wage hike with no proper improving measure might not have a positive effect Moon’s economic policy.

It is not only family merchants and small-scale businessmen in cities who suffer from a minimum wage hike. Rather, it has stronger after-effects on the agriculture and fishery industries. Given the characteristics of agriculture and fishery in which labor costs account for great proportion of the costs and the industries dependence on low-wage labor, it is probable that a labor cost hike will be directly linked with the shutdown of business in these industries. The sharp increase in the minimum wage is fatal to the industries which normally employ lots of foreign workers growing or raising fruit, livestock, aquaculture, and coastal fishery. The wages of foreign workers, who could be employed only for KRW 1,450 thousand a month last year, have risen to KRW 1,690 thousand this year, and will rise to KRW 1,870 thousand next year. As for foreign workers, accommodations as well as wages should be provided to them, and so the burden grows heavier. Most foreign workers in agriculture and fishery are provided by their employers with accommodations, but the cost for board and lodging amounting to KRW 400,000~500,000 per month and is not included in the minimum wage.

From the position of the current government that advocates an “income-driven” economy policy, the minimum wage hike is an essential prerequisite. However, too steep of a minimum wage hike to increase the income of low-income people has instead deprived low-income people of jobs and has caused the shutdown of self-employers’ businesses, which leads to the risk of economic slump. To minimize the negative effects of the minimum wage hike, first, the differential application of the minimum wage on the basis of business types and regions should be considered. Also, the government should come up with complementary plans for the minimum wage hike, which can be acceptable by both franchisers and franchisees. For example, if CU and GS25, the biggest companies in the field in South Korea, support 7.7% and 8.5% of their total operating profits for their stores, respectively, they will be able to bear 30% of the additional labor costs in the next year as the owners request. Additionally, the speed of the minimum wage hike should be controlled to match the reality of South Korea where the number of self-employed workers exceeds 25% of the total employment.

Su Yeon Ham is a graduate student with the China Studies Program at SAIS. She is currently an Intern at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Marcelo Druck’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.