The Peninsula

Pension Reform is a Top Priority for Korea

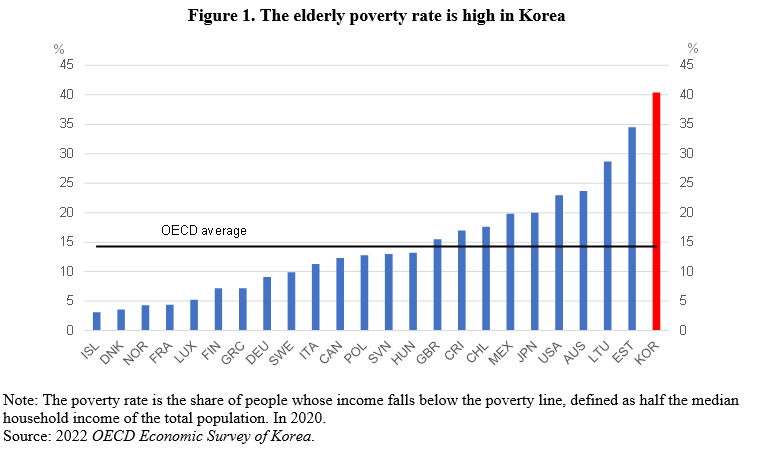

The 2022 OECD Economic Survey of Korea, released in September, highlighted the need to strengthen the social safety net. In particular, the share of the population aged 65 and older in relative poverty exceeds 40%, nearly triple the OECD average (Figure 1). Ensuring adequate retirement income requires reforms to improve the National Pension Service (NPS), expand the company pension system, encourage private savings and reform the Basic Pension.

Pillar 1: The National Pension Service

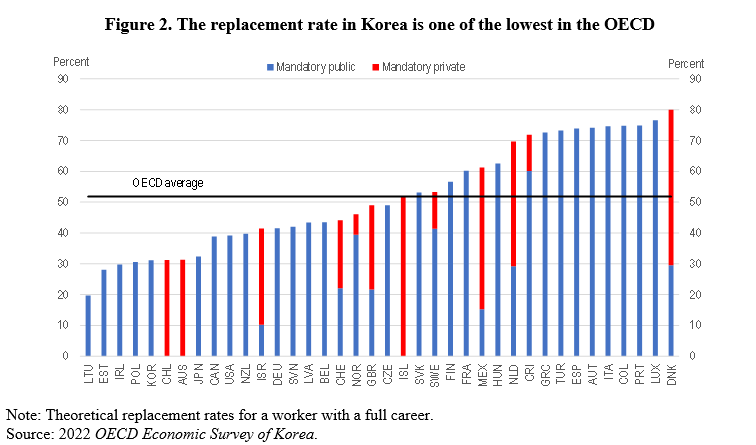

The Survey noted that the average pension paid by the National Pension Service (NPS) was only one-third of the minimum wage in 2021. The low pension amount reflects the short average contribution period of 18.6 years for new pensioners, even though the NPS was established in 1988. In addition, there are gaps in coverage. In 2021, only around 60% of the population aged 18-59 paid contributions to the NPS in 2020 despite the legal obligation for all workers to participate. Trust in the NPS has weakened as the targeted replacement rate (the pension benefit as a percentage of pre-retirement earnings) fell from 70% to 40% over 30 years. By the OECD measure, the gross replacement rate of a full-career worker with an average wage is 31%, far below the OECD average (Figure 2). Raising the targeted replacement rate is key to reducing the elderly poverty rate in the long run.

In addition, the Survey calls for lengthening the pension contribution period by extending working lives, in part by curtailing the practice of “honorary retirement.” Firms force a significant share of workers to retire before the mandatory retirement age (which must be at least 60), reflecting the seniority-based wage system that tends to boost wages above productivity for older workers. Moreover, the eligibility age for a pension is 62, thus exceeding the mandatory retirement age. Around two-thirds of those aged 55 to 64 in 2021 had left their career job before reaching the pensionable age. Their average retirement age was 49.3 and their job tenure was only 12.8 years. In 2006, the government introduced subsidies for the “wage peak system,” which freezes or gradually reduces the wages of older workers to encourage firms to retain older workers. By 2020, only half of firms with more than 300 employees had introduced the wage peak system, reflecting opposition from workers. The Survey states that Korea needs “a flexible wage system based on performance, job content and skills requirements.”

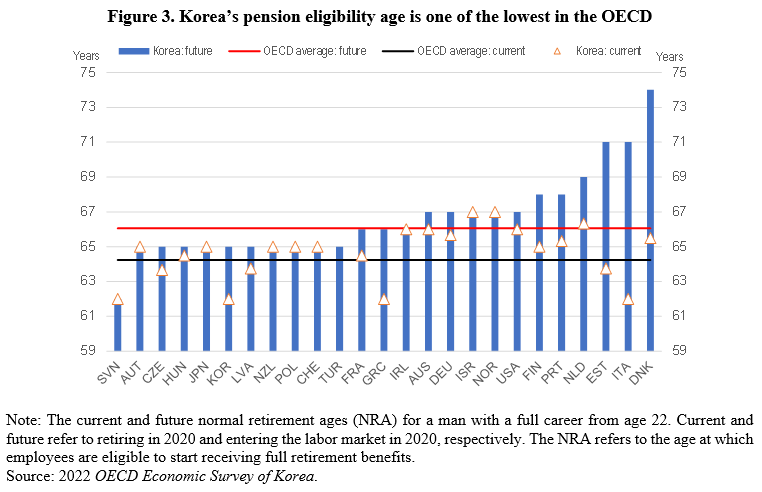

Pension expenditure is projected to triple by 2050 and the National Pension Fund would be depleted by 2057 under the current framework. The Survey points out that raising the pension eligibility age would support the financial sustainability of the NPS while helping to reduce elderly poverty and the impact of rapid population aging on the labor force. The pensionable age is 62, one of the lowest in the OECD (Figure 3). It is scheduled to gradually increase to 65 by 2034 but would remain low by international standards. With rising life expectancy, the expected time in retirement rose from 14.1 years for Korean men in 2014 to 18.4 years in 2020, and from 19.6 years to 23.2 years for Korean women. The Survey recommends that Korea “raise the pension eligibility age further than currently legislated by 2035 and link it to life expectancy thereafter.”

Another priority is to raise the pension contribution rate, which is 9%, half of the OECD average and among the lowest in the OECD. Under the existing framework, the contribution rate would need to more than double to finance the government’s current target replacement rate of 40% (by the Korean calculation) over the long term. Increasing the target replacement rate from its current low level would require an even larger hike in the contribution rate.

Pillar 2: The company pension system

The second pillar of Korea’s pension system is the private corporate pension, which allows employers to convert the mandatory lump-sum severance payments to a defined benefit, a defined contribution or Individual Retirement Pension. The severance payment, also called the retirement allowance, requires employers to pay one month of wages for each year of employment to departing employees. In 2021, 96% of those entitled to pensions chose the severance lump-sum payment.

Workers tend to prefer a lump-sum severance payment in part because of the prevalence of honorary retirement, which forces them out of companies at a relatively young age. The lump sum can be used to start a business to earn a retirement income. The lump-sum payments encourage firms to carry out honorary retirements because the lump-sum is a multiple of the wage at the end of employment, which increases rapidly with seniority. Firms tend to avoid establishing a corporate pension system, as it requires firms to entrust 100% of the funds to financial institutions, in contrast to the lump-sum payment, which does not have to be funded outside the firm. This puts workers’ lump-sum benefits at risk should the firm fail. The Survey stresses the importance of shifting the lump-sum severance payment to individual pension accounts.

Pillar 3: Personal pension plans

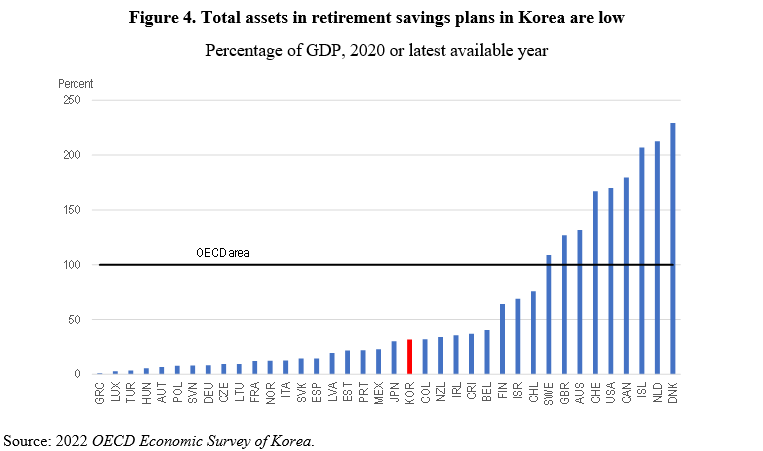

Personal pension savings in Korea are only 32% of GDP, compared to 100% for the OECD area as a whole (Figure 4). The low level reflects the relatively recent introduction of the system, low participation rates and low yields from savings. In addition, the tax advantage of personal pension savings compared to a benchmark savings vehicle is relatively small. The Survey suggests increasing the tax advantages and introducing automatic enrolment for all workers with the possibility to opt out to boost participation in personal pension plans.

Reforming the Basic Pension

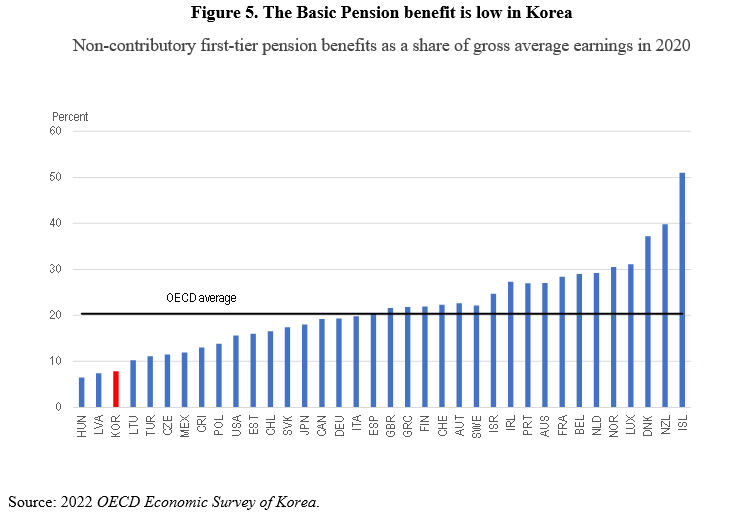

In the short run, the key to reducing elderly poverty is the Basic Pension, which was introduced in 2008. It is a tax-financed benefit that provides income to those aged 65. The coverage is very broad – around 70% of the elderly – but the benefit is low at 8% of gross average earnings (Figure 5), limiting its impact on the elderly poverty rate. Doubling the amount of the benefit would only reduce the elderly poverty rate to 33%, still far above the OECD average (Figure 1). The Survey concludes that the benefit should be increased while better targeting it on those with the highest needs.

Conclusion

President Yoon’s government plans to reform the pension system. A reform should take steps to sharply reduce elderly poverty while creating a financially sustainable public pension to provide income to older persons. It is essential to boost private pension savings – namely the corporate pension and personal pension plans – as additional pillars of income for the elderly.

Randall S. Jones is a Non-Resident Distinguished Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Shutterstock.