The Peninsula

Is “Byungjin” Working? A Look at North Korea’s Money

By William Brown

The short answer is yes, but probably not the way Kim Jong-un was thinking. An increase in the domestic use of U.S. dollars, brought on by lack of trust in the North Korean won, at last seems to be stabilizing Pyongyang’s monetary system and may be creating an environment conducive to normal private economic activities. The government is playing a positive role by not stopping the use of foreign currencies and, presumably in order to control inflation, seems to allowing something of a capitalist style banking system that allows private savings with significantly positive interest rates, anathema to doctrinaire socialists. The trouble for Kim Jong-un is the large state sector can’t take advantage of these developments without major reforms so the gap between private and state activities may be growing to dangerous levels. Solutions exist but they could further diminish the power of the central government, probably not part of Kim’s “strong country” formulation.

Most discussions of North Korea’s economy include a question mark, or at least they should. Pyongyang releases virtually no economic data. To answer any good question we must resort to a combination of anecdotal information, North Korean propaganda, or data from foreign partners’ transactions with North Korea. Each of these sources comes with limitations.

We might then stir these data points together with what economic theory and experience tells us should be happening. This mix is true of our discussion here concerning how Kim is doing with his goal of building a usable nuclear weapon while, concurrently, creating a prosperous economy. We come to some tantalizing, though necessarily tentative, results on the economic side of this puzzle.

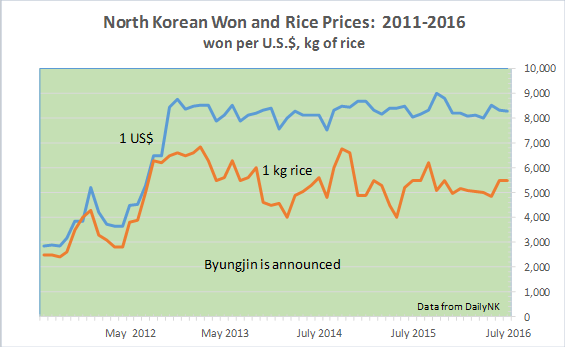

What does some of the available data tell us? The figure below includes monthly data on the market exchange rate for the U.S. dollar and the price of one kilogram of rice in North Korean won in the city of Hyesan, on the northern border with China. The data are painstakingly collected and reported by a South Korean NGO, DailyNK, with roots in North Korea, on its website.

The results, as one can easily see, are rather astounding. After decades of hyperinflation, and regular currency crises as real money began to supersede the Communist fixed price ration system, in late 2012 the price of rice stabilized and has even fallen since. A kilogram cost about 6,600 won when byongjin was announced and about 5,500 today, a drop of about 20 percent. Even taking seasonal considerations into account, since the price drops after harvest, there has been a slight decline. Granular reporting on prices of other commodities is not available, but since ancient times the price of rice has been one of the main markers for the Korean economy. It is doubtful other prices have moved much higher and anecdotal reporting indicates pretty good price stability of other marketable goods.

Even more surprising, given all the UN and U.S. sanctions, and the elimination earlier this year of the Kaesong Industrial Zone and its steady stream of U.S. dollar earnings, it took 8,490 won to buy a U.S. dollar in March 2013 and, slightly less, 8,285, today. So, the won has increased in value by 2 or 3 percent. Given a generally rising U.S. dollar around the world, holding won cash would have been a better deal than holding most any other foreign currency. Even better, a North Korean bank account is reported to yield 5.6 percent interest a year, at least for some depositors, making a won bank account a better deal than a U.S. or South Korean account.

So what is going on? Kim Jong-un came to power following his father’s death on December 17, 2011, and soon promised to fix the economy, saying no one would have to further “tighten his belt”. A little more than a year later, in March 2013, Kim added to his promise saying the country would proceed in parallel with the development of the economy and nuclear weapons, his so called “byungjin” development line. The U.S., among many foreign powers, have denounced that policy saying that Kim can’t have both prosperity and nuclear weapons, and has imposed layer upon layer of sanctions to prevent that from happening. One might have expected these moves to have caused North Koreans to flee to the safety of commodities and the U.S. dollar, trading in their won at ever cheaper rates, but this does not seem to have happened.

Since we don’t know what is providing this stability let’s look at several possibilities from a theoretical standpoint. It’s useful here to remember Milton Friedman’s simple way of explaining inflation, as “too much money chasing too few goods”.

- One possibility is the data is wrong. Without reliable official reporting this certainly could be the case. But rice prices are relatively easy to tabulate and they compound, so a mistake one month would have to be replicated the next month and so on. This seems unlikely. Political bias is often a problem in North Korea analysis but there is no particular reason to see why DailyNK’s reporters would bias such data, especially in this positive direction.

- Perhaps the price setting mechanisms are working; the price bureau simply sets the price ceiling at about 9,000 won per kilogram and the buyers and sellers fall in line. This is likely part of the answer, since posters in marketplaces state the price ceilings and rice is a commodity with more restrictions than any other. But this was the case long before 2012, so what changed? And market participants deny they pay any attention to the ceilings. It’s been a while since we have seen a public execution for someone breaking price rules.

- The government or the Party intervenes in the market to hold prices steady, that is they buy rice when it is too cheap and sell it when it is too high. This was a common practice in the Chosen Dynasty so it is not unthinkable that Pyongyang is reverting to that very capitalist minded process now. This requires a very tight control of the money supply or the government will constantly be on the losing side of the equation, as it often was in earlier efforts to squash market prices.

- Per Friedman’s dictate, perhaps the Central Bank is limiting the supply of won or credit. This would imply the government’s budget is in a strong position, and that won outflow was equal to or less than won inflow. This seems unlikely given the government’s huge expenses and the observed weakness in state production—profits from state enterprises are a key income generator for the state. These must be low or negative, given the dilapidated condition of state owned industry.

- Perhaps rice output is up and there are generally more goods and services available to attract the won. This is likely part of the answer. Weather has not been particularly good for agriculture in recent years but rice and other food production may be increasing as small reforms to the system encourage more individual initiative, both in growing and, maybe more importantly, in distributing grains. And liberalization is certainly allowing more types of goods and services to be provided in the market places, possibly competing for rice and lowering its price.

- It is possible that the border with China has become so open that North Korean prices are now determined in China—an informal monetary union, in effect, with yuan or dollars operating on both sides. Yuan has been fairly stable with respect to the dollar as well so this might make some sense. But China is supposed to be imposing sanctions and surely it would be protecting its farmers and industry from the unregulated capitalism in North Korea that this monetary union would imply. And to protect its own subsidies of agriculture, China often prohibits exports of grain. Other Chinese consumer products are flowing into North Korean markets, probably paid for by Chinese remittances or North Korean service exports, and these extra products may be dampening inflation—more goods, less money.

- Monetary and system reforms are stronger and more liberal than we think. For instance, on March 15, 2011, after a new President of the Central Bank and a new Chairman of the State Price Commission were installed, interest rates on won deposits were said to have been raised from 3 percent per year to 5.6 percent, according to the South Korean Institute of Far Eastern Studies. This followed the disastrous 2009 monetary reforms that Pyongyang had to rescind given the public outcry. Interest rates would not have mattered in the old system, where deposits were mandatory, prices were meaningless, and it was nearly impossible to withdraw funds, but apparently banking rules have been changed and ordinary withdrawals are possible. This might have temporarily increased the money supply, and inflation, but over time would have encouraged the public to start using banks in a normal way. It is difficult to see that this would have such a desired effect so quickly, however. And it would mark a significant break from socialism where “money is not supposed to make more money.” Still, this is likely part of the answer. Confirmation of real interest rates in North Korea is something we badly need.

All of these may be playing a role but the most likely explanation is less favorable to Kim’s prospects and more favorable to the North Korean public. And this is dollarization, a phenomenon in which foreign money enters an economy, replacing won as a “store of value”, a key characteristic of money. One might think this means more money in circulation and would thus be inflationary, but in a dollarizing economy the new foreign money may act more like a new good, something useful to hold on to. So for a time, North Koreans anxious to create some financial security would spend as much won as possible to buy dollars, or Chinese yuan, even illegally. But as policies have evolved, especially after the 2009 debacle, demand for dollars would first soar, lowering the relative value of won and creating hyperinflation. But hard cash doesn’t earn interest and as the won began to stabilize, along with the new potential to put it in a bank and earn reasonable interest, private savings even of won may have begun to rise, taking the heat off of inflation. Once reaching a “tipping point” it might have become apparent to savers that their won was not falling further and that it stood as a useful alternative to ever more expensive dollars. In other countries where production for private consumption is a large share of the economy, this rise in savings would have stalled economic growth, but in North Korea, where private savings had not been allowed, and where the state controls most production, the impact on aggregate demand would have been smaller.

Analysis of Latin American countries in the 1980s, when dollarization was rampant, showed a similar tendency. Inflation subsided but economic growth slowed as well, as private savings rose and spending declined. So his might be happening in North Korea, more savings and less growth.

If dollarization is a cause of price stability, what does it portend for Kim Jong-un’s “byungjin” policy? As in Latin America, it suggests big problems for government-sector finance, as private finance takes over and Pyongyang can no longer print money—U.S. dollars—to meet its bills. Higher real interest rates, moreover, play havoc with state enterprises in need of capital. Either Pyongyang slashes the already low real incomes of its huge bureaucracy and military—say by sharply raising ration prices, or like, China, it starts a long process of selling off state property and trade licenses to pay its bills. Either way, the economic part of byungjin might work, but better for private citizens than for Kim’s government.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Main photo from BRJ INC’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons. Internal photo by William Brown.