The Peninsula

Comparing Skill Sets Among Korean and American Adults

Published October 17, 2013

Category: South Korea

By Phil Eskeland

Last week, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released a report[1] on the level of skills among adults in 24 developed countries, including the Republic of Korea and the United States. There were several interesting analyses, comparing the skill level of adults in these nations based on age, education level, occupation, and immigration status. Overall, the OECD concluded that “developing and using skills improves employment prospects and quality of life as well as boosting economic growth.”

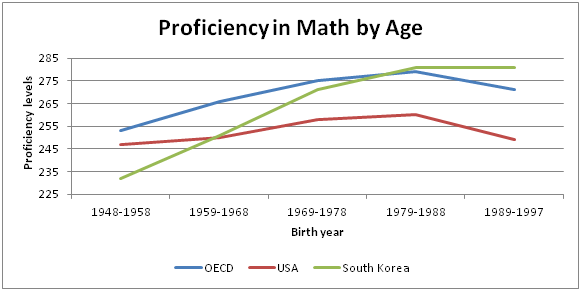

The data in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) report reveals an interesting observation as it relates to Korea and America. The basic math and reading skill set of Korean young people (those between the ages of 16 to 34) exceeds not only the OECD average but also the proficiency levels of young people in the United States. This reverses a trend where Americans exceeded the literacy and math proficiency scores of South Koreans of those born before 1968. In fact, the proficiency scores[2] of younger Americans are on a downward trajectory, going from 276 (among 25-34 years old) to 272 (16-24 years old) in reading skills and, more dramatically, 260 (among 25-34 years old) to 249 (16-24 years old) in numeracy or math skills. Yet, for the same cohort in Korea, literacy and math skills continue to consistently rise in each age group, going from 244 (among 55-65 years old) to 293 (16-24 years old) in reading and 232 (among 55-65 years old) to 281 (16-24 years old) in math skills. From the accompanying charts, the skill set of adults in Korea is still on the rise while the skill sets of Americans (and other OECD nations), after steadily increasing in the post-World War II era, have peaked and are now in decline.

This observation is not an anomaly. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores for 15-year-olds confirms this trend. Korea was ranked second in reading, fourth in math, and sixth in science among 70 developed and emerging economies. Yet, the United States ranked 17th in reading, 23rd in science, and 31st in math, which is below the OECD average. While this PISA score was based on tests taken in 2009, the results of the next round of testing that occurred in 2012 will be released on December 3, 2013. Based on this Survey of Adult Skills, one can project that the PISA score for 15-year-old Americans may not marginally improve.

What does this mean for the future? The United States was built by an entrepreneurial spirit and those willing to be creative by taking a chance on a new innovation. Many well-known innovative companies that we take for granted today were started by those in the born into the Baby Boom generation, such as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. Their generational compatriots had a basic math and literacy skill set that approximated or exceeded the OECD average.

Now, the table is turned. One of the key findings of the Survey of Adult Skills by the OECD is that “young Americans rank the lowest among their peers in the 24 countries surveyed” while “young Koreans…are outperformed only by their Japanese peers.” This survey should serve as a wake-up call to America. Improving basic skill sets, particularly among young people, is foundational to future economic growth and prosperity in any country. Korea has learned this lesson, which will help its effort to cultivate the “creative” economy in the coming decades. America has to re-learn this fundamental lesson in order to reverse the downward trend in reading and math proficiency levels of its young people; otherwise, the future of innovation will migrate elsewhere. Nevertheless, the OECD report had two common recommendations for both nations: (1) encourage and enable their citizens to learn throughout life and (2) foster international mobility of skilled people to fill skills gaps through the promotion of cross-border skills policies.

Phil Eskeland is the Executive Director of Operations and Policy for the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from Poetprince’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[1] OECD Skills Outlook 2013 (http://skills.oecd.org/skillsoutlook.html)

[2] Proficiency levels are as follows: Below 226 is Level 1; 226-276 is Level 2; and 276-326 is Level 3. More details about the factors that comprise each level can be found through the link attached in the above footnote.