The Peninsula

Career Paths to the North Korean Politburo Part 1: Trends under Kim Jong-un

One prominent strand of North Korea watching takes the form of tracking individual personnel movements: the ups and downs associated with retirements, purges and the promotion of new favorites. Yet there is persistent doubt about whether these movements are really consequential, particularly in a highly personalist political system. We can get a somewhat more rounded picture, however, by looking at the career backgrounds of Politburo members in a more systematic way and linking them to contemporaneous policy statements. To do this, we collected each Politburo member’s career profile from 1993-2021, accessed from the South Korean Ministry of Unification. We then classified their backgrounds into six career paths–military, diplomatic, party, state, economic and provincial—recognizing that some individuals might move across categories; details of our coding scheme our outlined at the end of this post.

The core finding: after falling during the succession and early Kim Jong-un period, the share of the military in the politburo has reached its highest level since the late Kim Jong Il era. What this means, however, is by no means straightforward. Military personnel still serve at the whim of the leader, we see ample efforts to assert party control, and the trend could well reverse. Moreover, we provide evidence that some of the most recent entrants into the Politburo appeared to emerge from nowhere, suggesting that strong personal links to Kim Jong-un probably mattered more than career credentials or independent sources of power.

Nonethless, the evidence speaks to the leadership’s confidence in the military as compared to state and economic institutions. These patterns no doubt reflect the attention Kim Jong-un has paid to the successes of the nuclear and missile programs in the face of setbacks in other areas; there is a public relations component to these promotions, highlighting individuals who have played key roles in the weapons program.

But two other motives also emerge from this exercise. First, the appointment of military personnel does not necessarily mean neglect of economic issues. Rather, it reflects in part a new theory of economic growth. The regime has long advanced the view—fundamentally misguided in our view—that the country might “leapfrog” economic reforms through a single-minded focus on science and technology. We are now seeing these ideas morph into an approach that sounds a lot like China’s approach to military-civilian fusion. The regime seems to believe either that economic growth would be spurred by military projects or that the success in the weapons program can somehow be transferred to other sectors.

Second, the economic slowdown has clearly raised fears of wider political fallout. A number of appointments reflect straightforward security concerns: a focus on assuring that the severe economic pressures the regime is now facing do not become manifest in domestic protest and instability.

However these developments are interpreted, the conclusions are not happy ones. To the extent that Kim Jong-un sees technological advances in weaponry as a key to external bargaining, domestic legitimacy, and even economic growth those activities are likely to continue apace. Moreover, the approach outlined here reflects a policy turn in which the relationship with China is likely to play a much more significant role than seeking a way through the thicket of negotiations with South Korea and the United States.

We undertake this analysis in three steps; in this post, we look at some overall trends using data on the career paths of Politburo members. Next time, we look at particular periods of change in the Politburo under Kim Jong-un and the individuals who have come to office up through January of this year. In the final post, we look at more recent developments, continuing and even increasing evidence of personalism, and the broader policy implications.

Trends in the Composition of the Politburo

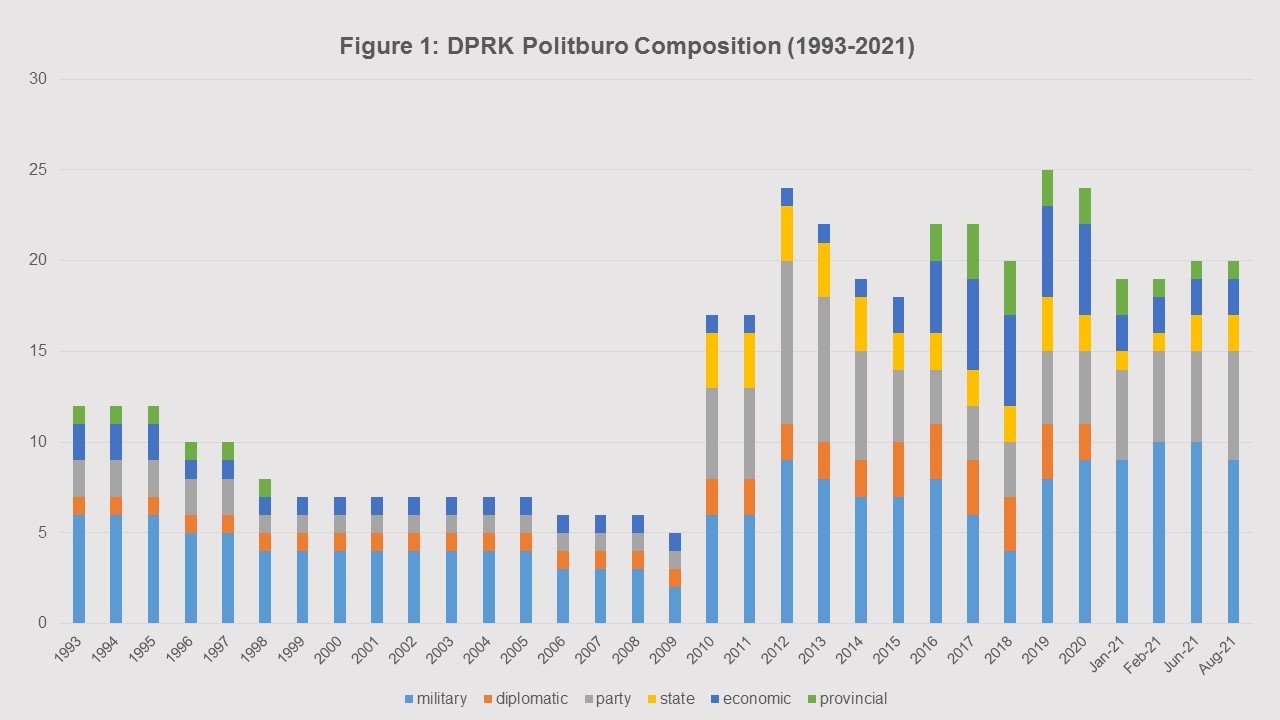

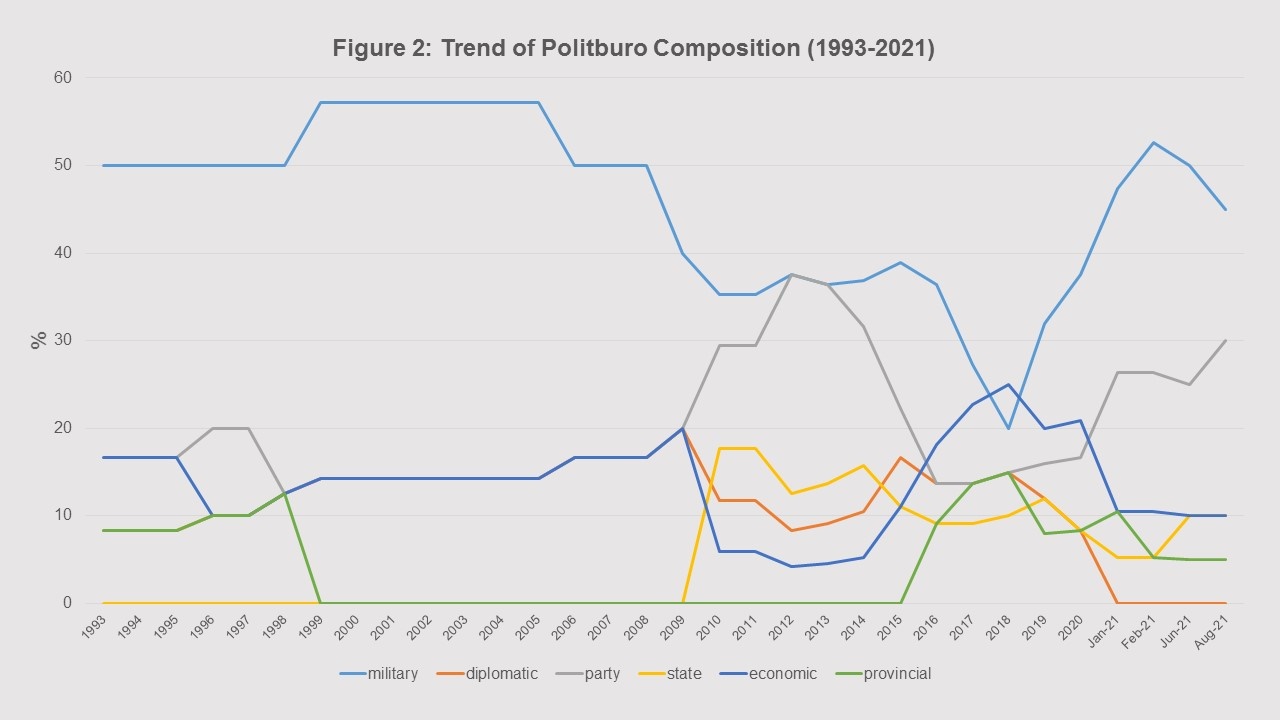

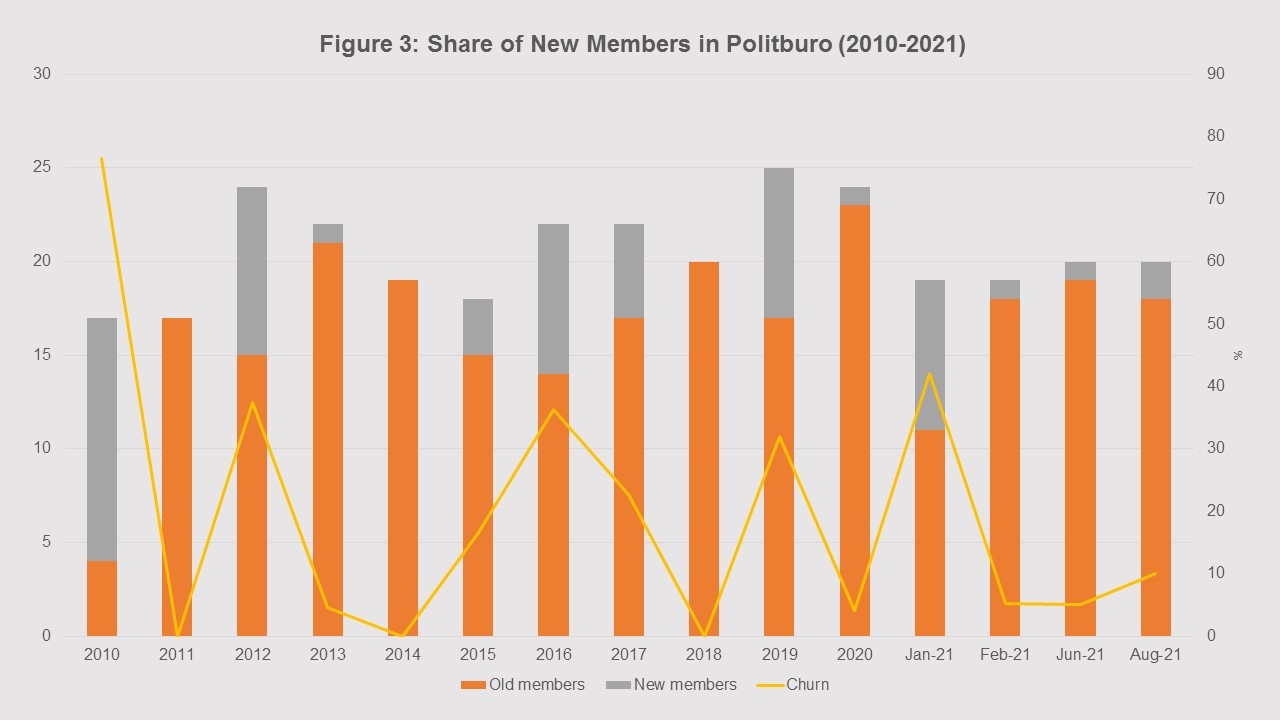

Figures 1 and 2 provide a simple coding of the main career paths of the limited number of individuals who have held positions in what is—nominally—the highest political body within the party outside of the Presidium. Although providing the same information, Figure 1 focuses attention on the overall size of the Politburo while Figure 2 underlines its composition by showing the share of members in each career track. Figure 3 looks at the data from yet another angle, focusing on the Kim Jong-un era. It shows the number of new members in the Politburo in each year (and month for 2021) as well as what we call “churn rate”: the share of new members in each time period.

The overall trends in Politburo membership have been a staple of Pyongyang watching, and the pattern is relatively well-known. During the Kim Jong-il era, the body atrophied and got older, shrinking to no more than five members by 2009 (Figure 1). Although not the locus of Kim Jong Il’s authority, which was in the National Defense Commission, the Politburo nonetheless had a high share of military representation, as can be seen most clearly in Figure 2.

A second interim phase—with appointments still controlled by Kim Jong-il—saw a remarkable expansion and diversification of the Politburo in 2010-2011. The standard interpretation is that this period was one in which the leadership sought to rally the top echelons of the political system around the succession process. As state and particularly party members came to occupy an increasing share of total positions from 2008 forward, the military share declined steadily.

2012 marks the onset of Kim Jong-un’s rule and was initially accompanied by promotion of non-mlilitary members. Although the body shrank somewhat from its peak, party elites reached their highest share of the body at the outset of the new regime. However, over the next several years, the share of both military and party members declined as individuals with economic and provincial backgrounds saw a rise in representation while state and diplomatic representation held constant. Figure 3 makes it easier to see the timing of these personnel changes, showing particularly large movements in 2012, 2016, 2019 and early 2021.

Yet two clear patterns emerge since 2018, the year of the failed Hanoi summit in February, and they are mirror images of one another. First, the representation of economic, state and provincial officials falls. Correspondingly, the party and particularly the military stages a comeback. After reaching an historical nadir of 4/20 (20%) in 2018, the share of military elites rises sharply reaching 8/25 (32%) in 2019, 9/24 (38%) in 2020 and 9/19 (47%) in January 2021 and 10/19 (53%) in February 2021 before falling back somewhat as a result of personnel changes in June and August.

Next time: a closer look at the discrete personnel shifts under Kim Jong-un.

Liuya Zhang is a PhD student in Political Science department of Ohio State University. She received her bachelor’s degree of Arts from Fudan University and master’s degree of International Studies from Seoul National University and master’s degree of International Affairs from UC San Diego. Stephan Haggard is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute and the Lawrence and Sallye Krause Professor of Korea-Pacific Studies, Director of the Korea-Pacific Program and distinguished professor of political science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy University of California San Diego. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone.

Photo from Boaz Guttman’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.