The Peninsula

Will Korea Ever Be Part of an Asian Union?

By Troy Stangarone

March 25 marked the 60th anniversary of the founding of the European Economic Community, the organization that would eventually evolve into the European Union (EU). The earlier European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), founded in 1951, was designed to provide European supranational control over coal and steel, the essential ingredients needed to fight a mid-twentieth century war. The European Economic Community, by contrast, harnessed the institutions of the ECSC to ensure a free market for the movement of people, goods, services and capital within a Common Market rather than extending centralized control to other economic sectors. While Europe pushed for regional integration after the Second World War, East Asia developed a series of bilateral alliances with the United States that underpinned the region’s security architecture and would not begin considering regional integration until the founding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967. Even with the founding of ASEAN, regional integration in East Asia has taken a more informal form than in Europe.

Yet, the idea of a type of union in Asia has been contemplated over the years. In the last decade, there have been proposals to create an East Asian Community by then Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio, an Asia-Pacific Union by then Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, as well as other proposals for some type of Asian Union. All of these proposals envisioned an Asian style EU. While these proposal failed to bring about greater integration in the region, ASEAN launched the ASEAN Economic Community in December of 2015 as part of a plan to create a region wide customs union among the ASEAN member states, itself modeled off of the idea of the economic elements of the European Union.

With the challenges that Europe faces with its own internal divisions and with the United Kingdom set to leave the EU, let alone the uncertainty of Korea’s own unification as a member of any Asian Union, it may seem fanciful to consider the question of whether Korea will ever be a member of an Asian Union. In fact, one might wonder if the idea of an EU in Asia will fade if the EU continues to struggle. However, the question also points towards the core of what is perhaps Asia’s most pressing future issue, how to shape the regional order.

In this context, Korean unification is a separate sub-issue to the broader question of the future regional order, which could help ease the path to Korean unification or further entrench the division between the two Koreas.

The question of order is becoming increasingly relevant in Asia as a result of changes in the region since the end of the Cold War. For much of the Cold War, the United States was the region’s dominate economic, military, and political power. The security architecture was built around the United States hub-and-spoke system of alliances, while the economic structure focused on trade with the United States. That began to change as the Cold War was ending. While Deng Xioping’s reforms began before the Cold War concluded, they were not truly felt in the region until the Cold War ended and China joined the World Trade Organization. With the Cold War over and trade expanding, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest trading nation in 2012 and as a result of production networks in East Asia has become the largest trading partner for many states in the region.

As China continues to grow in economic, military, and political influence, along with many of the nations of Southeast Asia, the regional political, economic and military order is in need of restructuring. The question for all of the nations in the region, Korea included, is what that order might look like. Will the order be shaped by the compulsory power of a single state? Or, will it be shaped by institutional power jointly agreed upon by the states in the region?

If the system in East Asia comes to be shaped by compulsory power, it will likely mean that the U.S. has receded from the region as an influential player and that China is able to directly exert its will on the neighboring states. However, if the region is shaped by institutional power, through the development of institutions that reflect common rules and norms governing the region, the states of the region will have developed a mutually acceptable order for the region that would help preserve long-term stability.

If the region seeks to develop new institutions to govern the regional order, it will face challenges different from those faced in Europe. The process in Europe was often driven by Franco-German cooperation. As the two largest states, and source of conflict in the two prior wars, France and German were able to help guide the development of institutions in Europe. Beyond cooperation by two states central to the project, there was a core group of states with Italy and later the UK that were fairly equal in population and GDP that helped to serve as a balance of near equals in the process so no one state could dominate.

In Asia, balanced institutional development could prove challenging in light of China’s size relative to the other states in the process. Institutional development has been largely ASEAN led to date, and that could be one path forward if China is willing to defer on leadership to ensure a cooperative process that maintains regional stability. To reach a sustainable order China would need to be willing to yield some of its interest and influence to the rest of the region. This may prove difficult. China’s comments in the recent past about it being large and others small, along with other actions, suggest that China may be unwilling to accept a structure that would inhibit its freedom of action. Regional suspicion of China’s long-term intentions and lack of faith in their ability to influence China leads countries of the region to welcome a counterbalancing U.S. presence in East Asia.

However, U.S. involvement now may be in question. Prior to the election of President Donald Trump, there was an expectation that the United States would play a role in shaping any new order in the region. The issue had not been so much whether the United States was declining as was commonly discussed, but rather how to shape the region as China’s power grows equal to the United States. With President Trump having withdrawn the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the United States’ role is less clear as TPP was to be the foundation for a new economic architecture in the region.

In terms of regional economic integration, Asia still lags compared to the EU in terms of intra-regional trade. While 70 percent of European exports are traded within the EU, only slightly more than 50 percent of Asia’s exports are traded within East Asia. Given the region’s dependence on the United States and Europe as a final destination for goods, that is perhaps not surprising.

If more work is still needed regionally to reach the type of economic integration seen in Europe, it is the area of political cooperation where Europe’s successes and failures may help to identify the challenges that Asian leaders will face. As part of the European integration process, European states began placing a wider range of competencies in the EU and, crucially, accepted majority voting as a basis for rule making. While some of the regulatory steps were a logical conclusion of the development of the single market, the EU began regulating in a wider range of domestic policies such as environment, justice, and public health.

In Europe, the public has begun to question whether the member states should take back competencies from the EU in areas such as immigration, one of the driving factors in Brexit and one of the goals of the ASEAN Economic Community. As countries in Asia consider any new order, one of the lessons of the EU is that moves towards greater integration beyond trade and the development of a security architecture could be problematic. Defining which policy areas should be subject to regional integration will be as much a challenge for Asia as it has been for Europe.

Another lesson from Europe is that it is possible to separate the security architecture from the economic architecture. Despite the development of an EU common foreign and security policy, NATO, with its ties to the United States, has remained the cornerstone for European defense. In the past, some in Europe saw NATO and the EU as competing organizations. It is now generally accepted that they have complementary roles. While Asia is unlikely to develop the type of collective defense structure we see in Europe for the foreseeable future given regional rivalries, the European case does suggest that the United States can continue to play in important role in providing stability in the region if it is unable to play a role in developing a new economic order in the region.

For Korea, the EU may also provide insights into how Asian integration could help with Korean unification. One of the EU’s great successes has been that it was highly successful in helping the former Communist states of Eastern Europe transition to market based democracies. Asian institutions that set common standards and norms could play a similar role in helping North Korea in the future transition as well by giving it a set of common standards that it must meet, as was the case with EU applicants, and ideally a broader organization to help in that transition, as it transitions either as a state or through unification to being a part of the regional order.

While there are no countries in Asia currently calling for an Asian Union, Asia is slowly moving in that direction as the logic of integration asserts itself and states of the region seek to develop a new economic order. Whether that order is a form of the TPP without the United States or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, it will lay the foundation for the region’s future architecture. The European Union was not established as the entity that we know today, but rather as an initial step to work together in the areas of coal and steel. While it is not certain that increased cooperation in Asia will continue to lead to greater cooperation, that was how the process in Europe was driven. In the case of Asia, it will be important not to look to Europe so much as a model for integration due to the differences in the two regions, but rather as a guide to the types of challenges that may arise as Asian countries seek to work together more closely.

Troy Stangarone is the Senior Director for Congressional Affairs and Trade at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

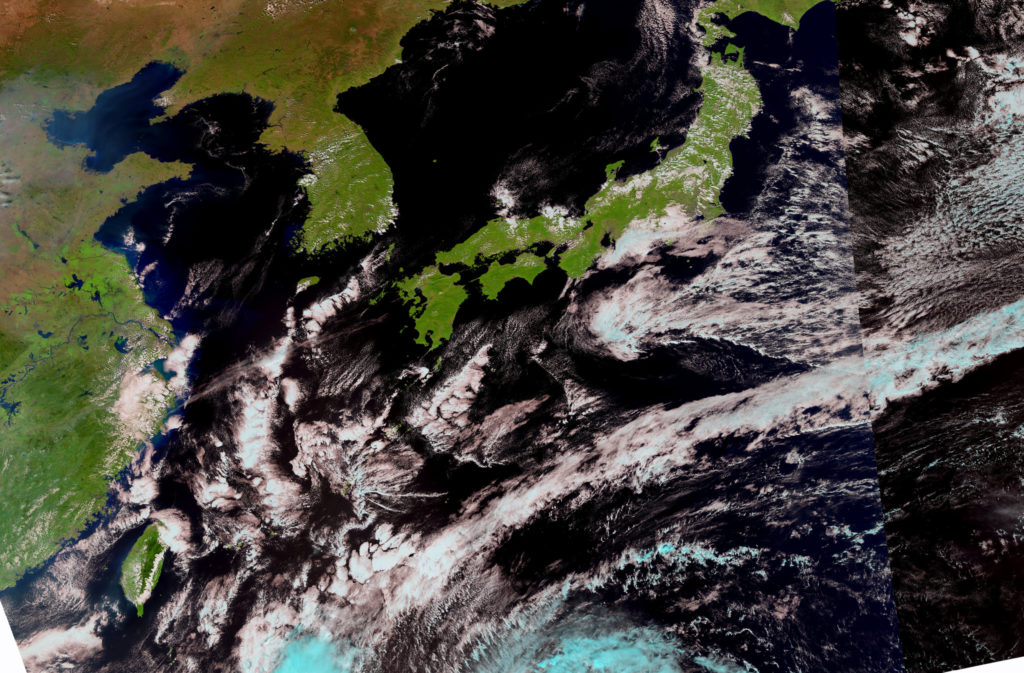

Photo from Stuart Rankin’s photostream on fickr Creative Commons.