The Peninsula

Why Are Fewer Women Defecting From North Korea?

Published October 31, 2012

Category: North Korea

By Clare Hubbard

The 2012 Heritage Foundation/ Wall Street Journal Index of Economic Freedom ranks North Korea last, after Cuba and Zimbabwe, with an economic freedom score of 1. However, in the mid-1990s famine when women and men had to focus on securing food by generating income and bartering for staples and foodstuffs, small-scale markets developed. The socialist system started to break down but it was still important for men to retain their state jobs to meet security requirements and have access to the welfare provided by the work unit. Women, on the other hand, either lost their jobs or left them to find other ways to generate income. Due to female microentrepreneurships giving North Korean women extra income, they have been able to defect in higher numbers than men; however, with North Korea pursing economic developments, the same women who might defect see a chance to make a profit and live more contently in their own country.

Money is essential when defecting from North Korea. Bribes ranging from $100 to $1,000 (during a Pyongyang crackdown) have to be paid to border guards to allow passage without being shot at. Money is also needed for hiring a guard to take you through the Asian Underground Railroad, paying off officials and Chinese police. It can take years for North Koreans to accumulate enough money to defect. Women account for a high number of defectors because they have the capacity to earn enough money to defect through their entrepreneurial efforts in small markets.

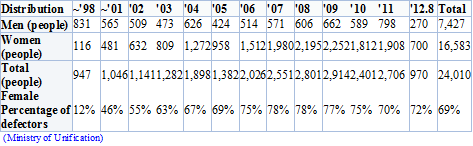

In 2002 economic reforms were passed that allowed general markets to exist in North Korea, and this is the same year that women became the majority of defectors. In 2004 men were banned from working in the markets, giving all the business to women. Women either lost their jobs or left in pursuit of more lucrative market opportunities. In 2005 there was a drop in total number of defectors. This drop could be due to policy reversals of the 2002 reforms in the fall of 2005, banning private trade in grain. As a result of the ban on private trade people started to defect because of worsening economic conditions leading to a higher defecting rate in 2006 and 2007. By 2006 markets were back to selling a variety of goods and North Korean women represented ¾ of the people defecting. Females stayed in the 75-78% range until 2011 when they dropped to 70 percent. Three explanations can explain why percentage of women defectors dropped:

1) Tightened security of the Chinese-North Korean border on both sides.

2) More available visas to work abroad and the ability to renew these visas after the first trip.

3) Women being more content with the current situation in North Korea.

Tightened border security could be a factor in declined defection because the control around the Chinese-North Korean border is said to have been boosted by both sides after the death of Kim Jong Il on December 17, 2011. However, the security was also said to have gone back to normal in January/February 2012. With border security at the same level of strictness as before and females earning enough money in their entrepreneurial careers to bribe guards their opportunities to defect became are the same as before and it can be said that tightened security is not a major factor in the percent of female defectors.

Legally, North Korean citizens are permitted to go to countries like Russia, China, Kuwait, Cambodia, Africa and Mongolia on work visas. They leave on two year visas and now can return abroad once they’ve come home. North Korea sends workers abroad to work in factories, restaurants and construction so that they can reach their fiscal goals. While abroad North Koreans are not allowed to travel in their host country or have extended interactions with locals. Their housing is usually located in or very near their work environment to prevent as much interaction with foreigners and the foreign culture as possible. Only North Koreans with very secure family backgrounds are allowed to take these jobs and their family acts as “hostages” to assure their return. A benefit for the workers is that they earn a little bit more money than they would if they worked in North Korea. Even though these North Koreans have the ability to work in a different country they are not defectors in the sense that they do not have the mindset that defectors do: they are content with their role in North Korean society and they have no desire to leave.

While this could be the start of a new trend or just a glitch in the numbers, one thing is certain, there has been a change in the percentage of female defectors reaching South Korea. Factors of this change could be due to economic reforms, never announced but quietly implemented, encouraging North Korean citizens to stay. Or, the news of stricter borders could be discouraging potential defectors to leave now due to the perceived danger, waiting a little longer until they are assured security is back to normal. North Koreans might be delaying their departure to see if the new regime will take a different approach in leading the country. The number of female defectors declining is most likely due to financial contentment in the freedom through street markets where women can make a profit and no longer feel like they have to defect to survive financially. However, the surge in inflation could also be impacting the ability of women to defect and undermine the possibility of economic reforms playing a role in the declining numbers. North Korea is undergoing major inflation made evident through the rapid increase in the price of rice and its exchange rate. This surge is expected to worsen if the harvest, as predicted, comes in low. Inflation is eroding the savings of many citizens and makes it harder to make decent profits through the markets, even as the state is making market trade easier.

However, economic developments could give North Koreans more opportunities to pursue microfinancing by selling their extra crops in markets and then using their profits to give loans with interest to other citizens. There have already been whispers of microfinancing from border NGOs that have talked to recent defectors about the economic situation. Economic development, Special Economic Zones and the fact that a million North Koreans now have phones are all signs that the country is opening up. The future of Kim Jong-un’s developments could equalize the gender ratio of defectors as more even opportunities for men and women to prosper in the market continue.

Clare Hubbard is a former Fulbright Korea English Teaching Assistant and current intern for the Korea Economic Institute.

Photo from Sung Ming Wang’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.