The Peninsula

What the Recent U.S. Action on Steel Means for Korea

By Phil Eskeland

On April 20, 2017, President Donald Trump signed a memorandum for the Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, directing him to conduct a “Section 232” investigation into the national security implications of steel imports. Since the adoption of the World Trade Organization disciplines, Section 232 is now a rarely used portion of U.S. trade law that authorizes the Secretary of Commerce to “conduct investigations to determine the effects on the national security of the United States of imports of any article.” Unlike most actions on U.S. trade policy, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) of the Commerce Department, which is known more for enforcement of U.S. “dual use” export control laws, conducts the investigation. However, BIS also has a responsibility to examine the effect imports may have on the U.S. defense industrial base.

After the signing of this memorandum, many media analysts concluded that this initiative was targeted at China even though President Trump said “it had nothing to do with China” as the U.S. seeks further cooperation with China to deal with North Korea’s nuclear weapons ambitions. Nonetheless, there are good reasons for pundits to reach this conclusion based on the global overcapacity in steel production caused by China because many products that use Chinese-origin steel as a base material find their way into the U.S. marketplace.

However, for 2016, China ranked 9th out of all direct steel importers into the United States, below Turkey and Taiwan. While China’s overproduction (i.e., manufacturing more steel than is needed to meet domestic demand) has placed immense price pressure on all steel producers regardless of the manufacturing location, the fact remains that direct imports of steel from China have been on the decline. During the past three years, the value of steel imports from China have dropped by more than half from $2.8 billion in 2014 to $906 million in 2016. The downward trend continued in 2017 when the monthly value of Chinese steel imports declined from $77 million in January to $72 million in February. This may be as a result of various anti-dumping and countervailing duty orders put into place in the preceding years by the U.S. International Trade Commission to offset the many benefits the Chinese government often provides to its steel producers.

Nonetheless, if China is not in the proverbial “hot seat,” which country could be next? Canada is America’s number one importer of steel. However, second on the list is South Korea. Should South Korea be concerned? No – for the following reasons:

1) The last time BIS conducted a Section 232 investigation into steel in 2001, the agency (then known as the Bureau of Export Administration or BXA) concluded that there was “no probative evidence that imports of iron ore or semi-finished steel threaten to impair U.S. national security.”

2) The 2001 BXA report also concluded that the “Defense Department already has established domestic preferences that apply to all of the steel used in weapons systems.” In fact, the report projected that the Defense Department’s need for steel over the next five years would remain flat because a decrease in need for steel in ammunition and aircraft engines. This trend has accelerated even more with the use of composites in defense manufacturing such as in the F-35 jet fighter.

3) The global share of imports of the U.S. steel market are not that much higher now as during previous Section 232 investigation – 22 percent in 2000 vs. 25 percent in 2016. Since the 1980’s, the U.S. has imported at least 20 percent of its steel needs from abroad, except during recessionary periods.

4) The previous Section 232 investigation also concluded that most of U.S. steel imports came from “safe foreign suppliers, with the largest suppliers of these products being U.S. allies.” In 2001, the previous major suppliers of imported steel to the U.S. were from Canada, Mexico, and Brazil. Now, the ranking of major foreign steel suppliers is Canada, Korea, Mexico, Brazil, Japan, and Germany. The Republic of Korea (ROK) is one of America’s strongest allies and certainly would not deny the U.S. access to its steel. In fact, 80 percent of Korea’s imports of military equipment comes from the United States. Thus, it makes no sense for South Korea to restrict steel exports to America because it would directly harm the ability of the ROK to secure the best weaponry for its defense and hurt its own national security.

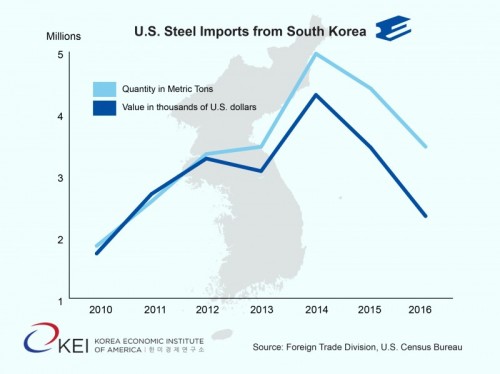

5) Lastly, following the overall trend, imports of Korean steel have also declined even as the dollar appreciated in value. There may be other factors dictating this trend, but this development does not undermine U.S. national security. In fact, U.S. imports of Korean steel continued to drop in the early part of 2017, going from $205.3 million in January to $169.4 million in February (latest data available).

Thus, while it is good for the U.S. to periodically review the possible effect of imports on U.S. national security, an independent investigation in 2017 should reach the same conclusion as BXA did in 2001. The circumstances have not significantly altered since that time. As a result, Korea should not have to worry about this report, due later this year, unless the issue becomes politicized. A more appropriate focus for the Trump Administration should be to bolster the Pentagon’s efforts to prevent the loss of key manufacturers or suppliers to the defense industrial base through the Diminishing Manufacturing Sources and Material Shortages (DMSMS) program. This initiative avoids the pitfalls of raising prices for all consumers throughout the economy by imposing higher tariffs on a certain product while insuring that the Pentagon still retains access to a key product or component, often made by a small manufacturer, for a defense item.

Phil Eskeland is Executive Director for Operations and Policy at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from Billy Wilson’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.