The Peninsula

What Newly Nominated Federal Reserve Bank Chair Jerome Powell Might Mean for South Korea’s Economy

Published November 27, 2017

Category: South Korea

By Hwan Kang

Although interpretations vary, the general consensus over President Donald Trump’s nomination of Jerome Powell as the new Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) Chair is that Powell is a safe bet. He is considered to be more or less aligned with former Chair Janet Yellen who consistently followed through on gradual monetary tightening, but does not completely go against President Trump’s expansionary policies in terms of regulations to the dismay of some economists. Therefore, it would be reasonable to believe that even though President Trump broke the tradition of re-upping a fed chair’s tenure with Yellen, Powell will likely continue her legacy by raising the Fed rate.

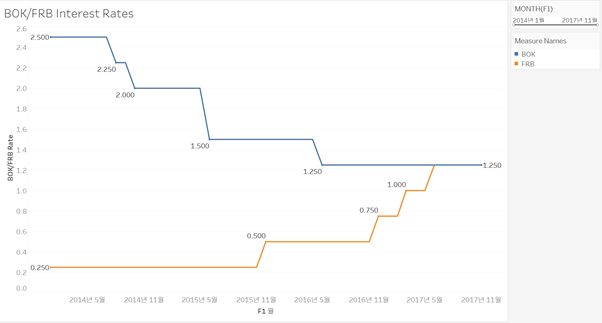

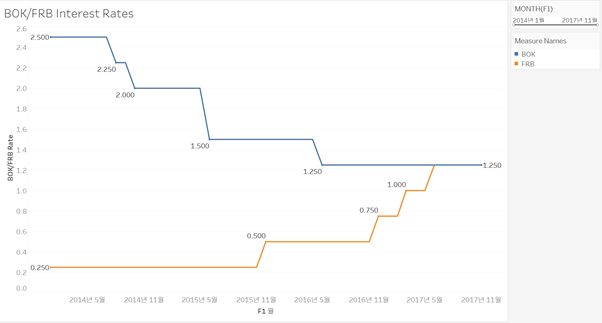

FRB Rate and BOK Rate

(Source: Bank of Korea, the Balance https://www.thebalance.com/fed-funds-rate-history-highs-lows-3306135 )

South Korea has been going in quite a different direction from the United States during Yellen’s tenure. The Bank of Korea (BOK), South Korea’s central bank, has not raised its rate for seven years. In fact, the BOK actually lowered the rate by 0.25 percent to 1.25 percent in 2016, even after Yellen began to raise the Fed rate in 2015. After Yellen was appointed in February 2014, the Fed rate and the BOK rate have continuously gotten closer because of contrasting monetary policies. The Fed rate has now reached 1.25 percent from near zero, which is the same rate as the BOK’s.

The FRB did not raise its rate this month, but South Korean experts are becoming more confident that the BOK will have to raise its benchmark so as to prevent the BOK rate from being surpassed by its U.S. counterpart. The reason is that, theoretically, if the Fed decides to raise its rate, the BOK should keep its rate higher to prevent foreign investment from leaving South Korea, which is vital to its economy. Simply explained, investors want to put their money where the interest rate is relatively higher and Korea does not want to lose that advantage. Another reason has to do with the U.S. dollar’s strength as a global currency, making it preferred over the South Korean won. So South Korea cannot be in the position of keeping the rate low and hoping that investors will keep their Korean assets. With such a background in mind, South Korea is facing looming pressure to raise its interest rates as the FRB is expected to continue its trajectory, which is not exactly welcomed news for the Moon Administration.

Why Not?

The significance of an FRB rate hike for the Moon era is closely related to the reasons why the BOK rate has remained constant all these years. Aside from foreign investment pulling out, the South Korean central bank and the government have been facing other concerns for quite some time.

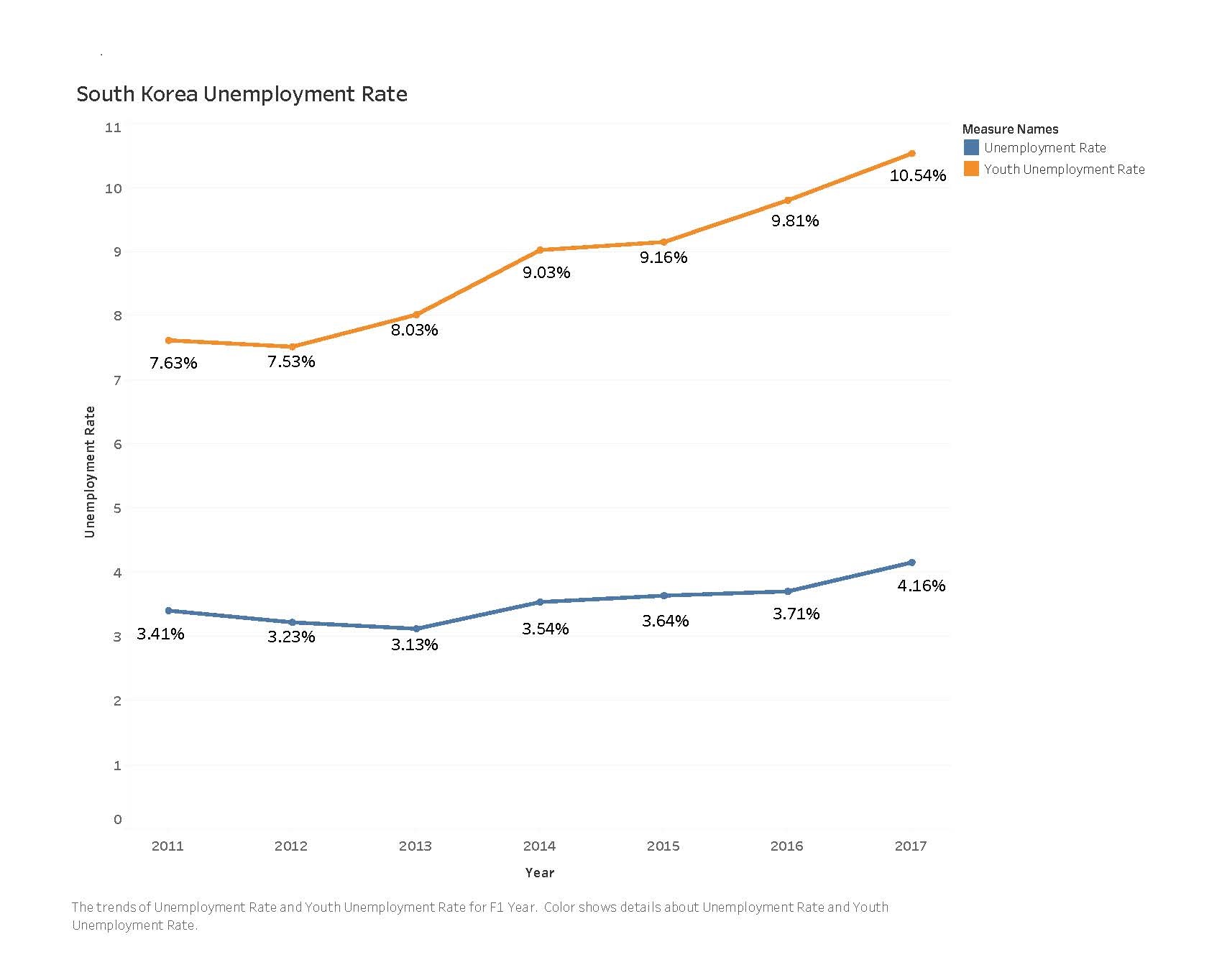

(Source: index.go.kr)

South Korea may have been experiencing moderate growth, but there are several economic indicators that are causing concern. For example, South Korea’s high youth unemployment rate and high rate of irregular employment (비정규직) are not improving. While the unemployment rate as a whole has stayed around 3 to 4 percent from 2011 to 2017, the unemployment rate for youths aged 15 to 29 has hovered well above that at 7 to 9 percent and has reached an average of 10 percent during 2017. Although this is generally lower than the United States, the U.S. youth unemployment rate has been sharply decreasing from near 20 percent to 9 percent while recovering from the Global Financial Crisis, when during the same period in South Korea the opposite has happened. Similar concerns are expressed over irregular employment, which is known in South Korea for a huge comparative disadvantage in job stability and wages, compared to regular jobs. The rate of irregular workers has been steadily decreasing, but it still remains around 32 percent of the total employment. Monetary tightening in such a state would strain companies in their market performance or rise costs for corporate debt, which in one way or another will affect their decisions to hire new people in the future.

Along with unemployment, South Korea is also burdened with record high levels of household debt. Household debt is near 140 million KRW (127.4 billion USD), which is 95.6 percent of South Korean GDP and much higher than the OECD average, placing it 7th among OECD countries. It is also expected that the debt will increase even more next year, which is not good news when an interest rate hike is expected in the future and people will have to pay more interest on borrowed money. President Moon’s October agenda for household debt has this in mind specifically, coming up with fast relief measures such as delaying loan maturity for three years, setting lower interest rate ceilings, and buying nearly expired bonds in some cases. However, such measures came only after the Moon Administration enacted numerous regulations on restricting mortgage debt which some experts blame as the reason for sudden increase in credit debt.

With these factors in mind, if Trump had nominated a chair that would have pushed forward with lowering the FRB rate, as some would have expected from his usual political stance, it would have bought more time for the Moon administration to carry out its economy agenda. Although Powell is expected to increase the rate slowly, such a somewhat unexpected choice by Trump bodes ill for President Moon in that the fuse for a BOK rate hike has not been put out. On the other hand, the low BOK rate has been considered problematic for some period of time for being relatively low and stationary, which leaves the BOK little room to cut should a future economic crisis occur.

What South Koreans fear is another depression or economic crisis on top of the current economic situation with high unemployment and struggling business, as well as the North Korea security issue. After witnessing Japan’s “lost decade” and the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis, both of which were triggered by real estate market collapses, Koreans are wary of a similar economic depression. If, for some reason, uncertainty over the BOK rate pans out after the nomination of Powell and feeds such fear, sudden collapse might actually happen in self-realizing vicious cycle. Already a hint of such anxiety can be seen in the political arena as major party members are blaming the previous administration for keeping the BOK rate low for such a long period of time, also raising the question of the BOK’s independence from the government. However, instead of escalating the matter into another political dispute, South Korea needs immediate bipartisan support to brace the country for a possible economic adjustment as the BOK does its job in preparation for the Powell era.

Hwan Kang is currently an Intern at the Korea Economic Institute of America as part of the Asan Academy Fellowship Program. He is also a student of Seoul National University in South Korea. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Stefan Fussan’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.