The Peninsula

The Young Marshall’s Long Hot Summer

By William B. Brown

Let’s examine the North Korean economic scene in the hot Korean summer of 2018 to see if we can get hints at Kim Jong-un’s thinking on what arguably are the most important decisions the regime is making in decades. Pundits will argue who is more pressed for time, Kim, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, or U.S. President Donald Trump, but here we will just focus on Kim. As always, our information is sketchy and circumstantial, but circumstances can count.

What we know is that Kim and his controlled media have spent the summer pushing hard for economic progress, castigating weak state-sector performers—most recently a medical equipment plant chastised as contributing to weakness of the country’s health sector, pushing for progress against command economy five-year plan targets, demanding UN and South Korean sanctions relief, and admonishing farmers to take their water buckets to the fields in an epoch, at least since last year, battle against drought. On the up-side, we also know that despite the trade problems, the unofficial exchange rate has held steady, except for an interesting 3 percent slip in recent weeks, and that prices generally are holding despite a severe drop of imports. Electricity supply seems to be improved, possibly helped by the stoppage of coal exports and by a rumored Chinese supply of new equipment for an old power plant in Pyongyang. Also, electricity prices apparently have been raised, from nothing to something, still very low, which may be helping with distribution. And by defector accounts, Kim’s media turn to economic prosperity and less anti-U.S. rhetoric is being well received by a hopeful, yet anxious public.

Confusion in the Markets, on the Farms, and in the Factories

What we don’t know is whether Kim’s visits to China, the DMZ, and Singapore have encouraged economic reform, throwing off the last vestiges of the country’s long and catastrophic experiment with socialism. There are hints of massive decentralization and privatization under way but not driven by formal changes in laws, or in government messaging which continues to pine for “socialist construction” and the “people’s duty.” Contradictions abound. Some reports even hint at ending the collective farm system, the vital change that began China’s reform in the late 1970s, and allowing, in effect, family farming, but others indicate the state continues to demand most farm output and prevents private ownership of the “means of production,” most importantly, farm land. Meanwhile, authorities look the other way as entrepreneurs buy and sell apartments ostensibly owned by the state and allow, for a small fee, building private residences in the countryside. Some are getting rich doing so, others probably are sent to the gulags. State factories seem to allow managers discretion in producing and selling goods outside the plan for private gain, and at market prices for inputs and outputs, while the rigid state wage system remains for millions of workers, a paltry market equivalent of less than a dollar a month, plus rations, free housing, and medicine, for what they are worth. And for a hundred-dollar bill you can get an entrance pass from the policeman guarding roads into Pyongyang; where the money goes no one knows.

And we don’t have a good idea of how much foreign exchange the regime possesses and the rate it is being drawn down, how fast it circulates, or even if Beijing, or others, are secretly helping out with a few hundreds of millions of dollars. Its pretty clear, nonetheless, for much of the public, a secure vehicle for financial savings, greenbacks, finally exists, even if it earns no interest. To the extent dollars are being borrowed and lent, capitalism surely is creeping into North Korea, maybe in a big way.

We can only surmise that at the top of Kim’s concerns must be the value of his country’s money in terms of the ubiquitous dollar, and the impact of China’s near embargo on activities that allow the state to earn foreign exchange, financial issues that must make Moon’s budget and Trump’s “trade wars” look trivial in comparison. And other warnings must lurk around every corner. The potential for a poor harvest and starvation, given drought conditions through mid-August and few grain imports or aid, creates anxiety, everywhere. Sixty-year old wobbly Russian built electric power and water systems with spare parts often sanctioned, are a constant concern, at least for Premier Pak Pong-ju who seems to have responsibility for Pyongyang’s power supply and everything else in the economy. Huge variances in incomes, with state sector wages falling dangerously below private sector earnings and wealth must breed dissatisfaction. Extreme problems exist in the country’s planned sector, exposed by growing productivity in the uncontrolled and increasingly lively private sector. Unemployed textile workers—textile trade has been shut off by China, at least officially—would also seem to be a problem for the regime as should be out-of-work coal and iron ore miners and everyone in need of fuels. But at least it isn’t cold, yet.

Money and Trade

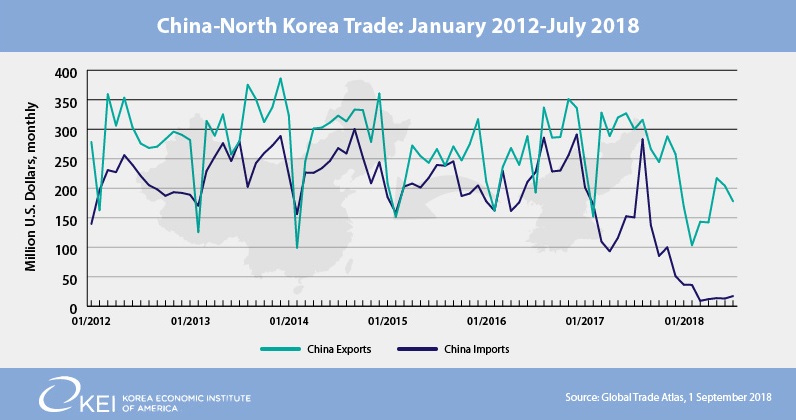

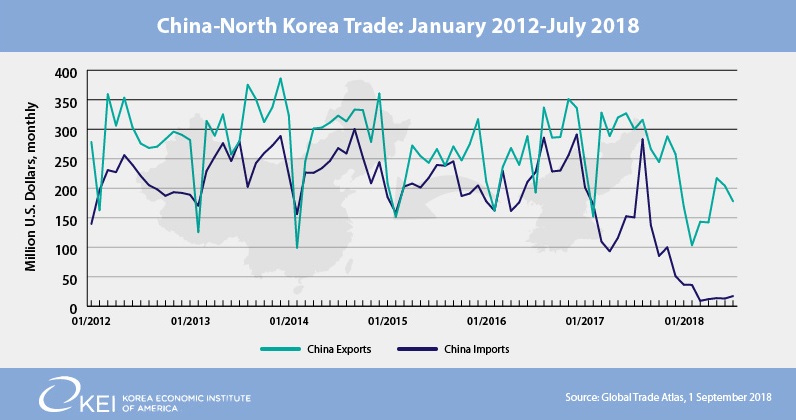

The trade shock imposed by China about a year ago, embargoing almost all purchases from North Korea and restricting some sales of petroleum products and various metals and equipment, must be near the top of Kim’s concerns. Year-to-date through July, official Chinese imports were only $124 million, down 88.1 percent from the same period of 2017.[1] And Chinese exports, no doubt suffering from the collapse in North Korea’s ability to buy, are down 38.9 percent, to $1,174 million. A small uptick in April and May is likely seasonally related. China’s customs bureau is having remarkable, but unspecified technical trouble releasing worldwide commodity-by-country data so it is not clear what exports, that is North Korean imports, are being affected the most. First quarter data, which is available, showed big downturns across the board, including electronic equipment (cell phones and computers), all kinds of vehicles and equipment, industrial materials, and refined petroleum products. Crude oil deliveries are probably being maintained at the long-term rate, about 500,000 tons (3.6 million barrels) per year, in accord with the UN sanctions agreement. These are not counted in Chinese trade statistics, presumably because they are delivered free of charge. This is the last big economic lever Beijing holds against Pyongyang. Elimination, or just charging for the oil, would cause havoc in North Korea, a fact surely understood by Kim as he travelled to Beijing last March.

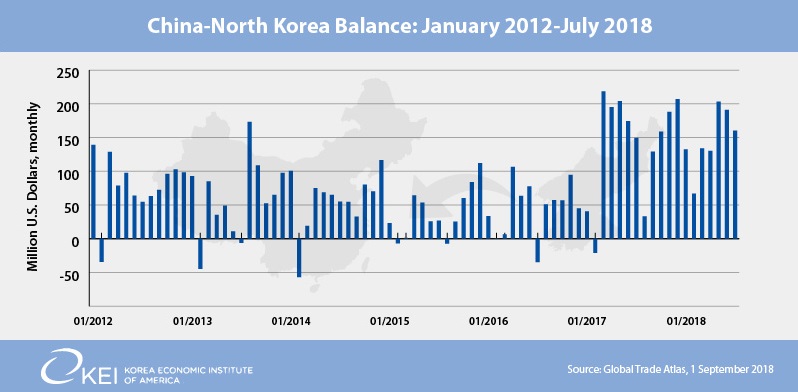

Western and South Korean news is full of reports of “smuggling” and “ship-to-ship” transfers by North Korean traders and a breakdown in the UN sanctions environment, post Singapore. Anecdotal reporting shows the embargo is not air tight, but the quantities and values involved are not easily aggregated. They are, to a degree, evidence of a tight official sanctions environment, otherwise such expensive and dangerous activities presumably would not occur. And commercial imagery of Nampo harbor, the country’s main container port, shows a big drop in activity in late August compared with the same dates in 2017 and 2016. Nonetheless, sanctions usually erode over time as dealers on both sides learn to work around them.

Source: Planet Labs, Inc via Voice of America News

Imports of refined products clearly are occurring, despite the UN ban; whether they substantially counteract the one-third cut in North Korea’s petroleum supply, and thus consumption, imposed by the UNSC, is hard to ascertain. Gasoline prices have fallen sharply from very high levels a year-ago, but recently rose modestly to 11,000 won per kilogram, equivalent to $3.90 per gallon at the unofficial exchange rate, about the same as in China.

Of even more critical worry to Kim, or least to his close advisors, must be the value of won. It has remained very steady, arguably too steady, during his six-year reign after falling catastrophically during his father’s rule. The steadiness, in effect a peg over the past six months, has come during a period of extensive dollarization of the economy; North Korea in 2018 is one of the most “dollarized” economies in the world, with U.S. and Chinese currency circulating at will alongside the domestic currency. For an economy that not long-ago used ration tickets, not money, to rule the economy, this is an enormous change, indicating a remarkable decentralization of economic and social power. This no doubt is not lost on Kim as he tries to hire tens of thousands of civilians to attend his parades and ceremonies. And as he tries to keep his million-man army reasonably happy on meager rations with essentially no pay. Its not clear how the won stability is being maintained. My guess is the central bank has subordinated monetary policy to keeping the dollar-won steady at about 8,000 won. To do that, in the face of a sharply deteriorating current account balance, means it must maintain an extremely tight policy, not making loans even to needy state enterprises, or printing new currency to be doled out by the government. In fact, policy might resemble that of a currency board economy, like Hong Kong, that fixes its currency against the dollar while allowing a liberal market to play out internally. A big difference, however, is that Hong Kong has enormous U.S. dollars reserves, and in fact backs its dollar 100 percent with U.S. dollars. North Korea’s reserves are unknown but, based on the sanctions led deterioration in its current account, appears to be losing on the order of $100 million a month.[2]

Interestingly, in the last few weeks the value of the dollar, and RMB, have risen about 3 percent against the won, the biggest rise in over a year. This must worry Kim, given a break in the peg could suddenly turn to panic selling of won, and huge inflation in the domestic economy. As in its 2009 currency fiasco, people could be in the streets but in much larger numbers given the new importance of money to their well-being.

Drought, or flooding, an ever-present concern

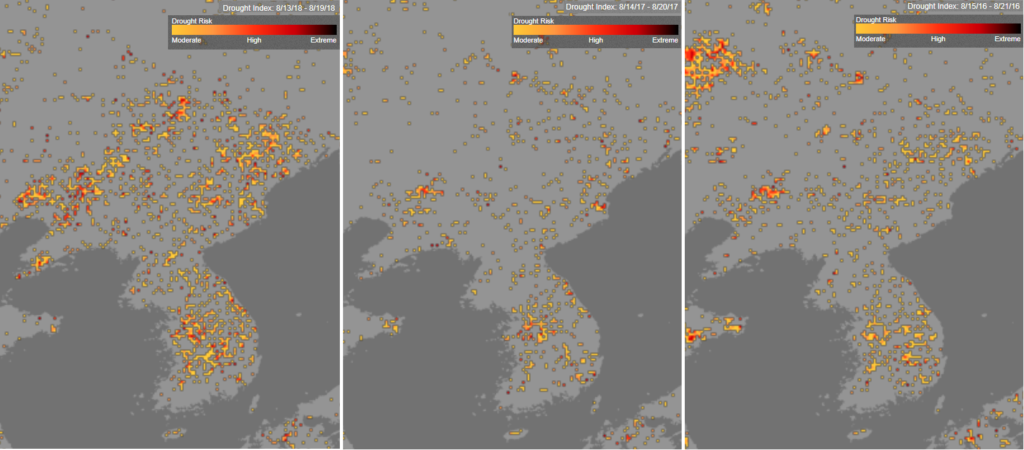

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies issued what has become an almost normal annual food emergency warning for North Korea in early August, owing to extreme heat and unusually dry conditions, and North Korean media is calling for drought prevention work, meaning huge bucket brigades and very hard work for the collective farmers. NOAA’s soil moisture maps show signs of drought in mid-August, worse than last year when, similarly dire warnings were issued by international agencies. A recent typhoon may have alleviated conditions, somewhat.

Source: NOAA via Voice of America News

In the past, North Korea could rely on foreign food aid supplemented by modest commercial imports to help fill the shortfall—although the gap is never completely filled for the chronically malnourished population. In 2018, however, the aid and trade situation is much more problematic, and thus likely more worrisome to Pyongyang. Filling a big shortfall, this time, could come with unwanted strings attached. So far, however, market prices reflect no particular concerns, with rice and corn prices relatively low and not rising, although this also could be the result of very tight monetary policy. We do not know the extent to which Pyongyang intervenes in the markets to try to stabilize prices and for how long it can do that.

Hints and hopes but no conclusions

Does any of this matter? Kim clearly is raising expectations for economic prosperity, but it is not evident he is allowing the tools to make that happen, whether via denuclearization and sanctions reduction, or economic reforms, or some combination of the two. It’s pretty obvious the “try harder” approach, as he is now pushing, is not going to work. Most likely he still hopes he can get by with partial moves on both fronts despite the dangers these imply for the security of the regime. Half measures, especially in the economy, easily can backfire with financial panic and social instability the result. And half measures on denuclearization, so far, have not reaped much in the way of sanctions relief.

American North Korea scholars, on the right and on the left, sometimes assert that Kim has no interest in the livelihood of the people, but that seems farfetched. Kim’s interest in economic development might be solely for regime security but that would hardly be unimportant and, we can all hope, just might be more important than the nuclear weapons that arguably are killing his grandfather’s communist dreams while endangering his own security.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from kokodoze’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[1] Global Trade Atlas, 1 September 2018

[2] This is a raw estimate based upon the change in trade with China. For decades Pyongyang has run about a $60 million monthly deficit in merchandise trade with China, according to Chinese data, not counting the crude oil. Since the country receives very little net investment on its capital account, this would suggest that the rest of the country’s merchandise trade balance, and the other items in the current account, probably give it a surplus of about that amount. Since last spring, however, the deficit with China has jumped to about $160 million a month, with no observed increased in income from any other source, and in fact likely declines as sanctions have been imposed on North Korean service and remittance income from abroad. So, at first glance, it is suffering a net $100 million in hard currency outflow. Either reserves will continue to drop or imports will suffer further declines, crippling industry and consumer well-being, dependent on these vital inputs.