The Peninsula

Setting Korea’s Fiscal Path

By Randall S. Jones

The Moon administration’s fiscal policy was expansionary even before the coronavirus pandemic. With government spending increasing more than 9% in both 2019 and 2020, the OECD projected last year that Korea’s budget surplus, which was nearly 3% of GDP in 2018 (on a general government basis), would disappear in 2020. The additional spending to support the economy during the pandemic, combined with falling tax revenues, will likely result in a significant budget deficit this year. In fact, the OECD Economic Outlook released on June 10th projects a budget deficit of around 3% of GDP this year, with gross government debt rising as high as 44% of GDP in 2021. The necessary fiscal response to the economic downturn in 2020 should be coupled by measures to ensure fiscal sustainability in the face of the long-term challenges facing Korea.

Korea’s fiscal position remains sound

In March and April 2020, the National Assembly approved supplementary budgets each equivalent to around 0.6% of GDP. On June 2nd, the government announced that the third supplementary budget will total 35.3 trillion won (1.8% of GDP), the largest ever.

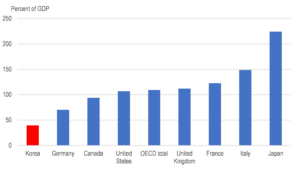

Korea’s government debt is low relative to GDP compared to other major economies (Figure 1). Interest rates are likely to remain low for an extended period, making debt more sustainable. Moreover, Korea appears less vulnerable to capital outflows during periods of turbulence than it was in the past, thus reducing financial risks associated with debt.

Nevertheless, the deterioration in the fiscal position has created some concern. It is important to establish a stronger medium-term framework that ensures Korea’s fiscal sustainability. The National Fiscal Strategy Meeting, held on May 25th discussed plans for the 2021 budget and the 2020-24 fiscal management plan.

Figure 1. Korea’s gross debt is relatively low

General government gross financial liabilities as a percent of GDP in 2018

Note: The OECD total is a weighted average of the member countries.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database.

A timely, targeted and temporary response to the economic downturn is the immediate priority

Korea’s measures to support an economic rebound and limit the long-term economic damage from the global downturn is appropriate. The 2008-09 Great Recession left a permanently negative legacy on growth potential by reducing capital accumulation and employment. In addition, the Great Recession caused the failure of companies that had successfully mobilized management, technology, human capital, suppliers and customers. Replacing them took time, resulting in a slowdown in multi-factor productivity growth.

Korea’s response to the Great Recession was “timely, targeted and temporary”. Additional expenditure was supplied by the supplementary budget of September 2008 – the same month that Lehman Brothers collapsed – and in the 2009 budget. The fiscal response was effectively targeted on employment; the government created 0.3 million public-sector temporary jobs in 2009, limiting the decline in employment to 0.4%. Finally, it was temporary. Spending soared at an 11.6% annual rate over 2008-09, but then its growth rate slowed to 2.5% in 2010.

As noted in the 2010 OECD Economic Survey of Korea, “Korea has achieved one of the fastest recoveries in the OECD from the global recession. The government implemented the largest fiscal stimulus package among OECD countries”. Fiscal support, combined with robust exports, kept real GDP growth in positive territory in 2009 (0.8%) and produced a strong recovery in 2010 (6.8%).

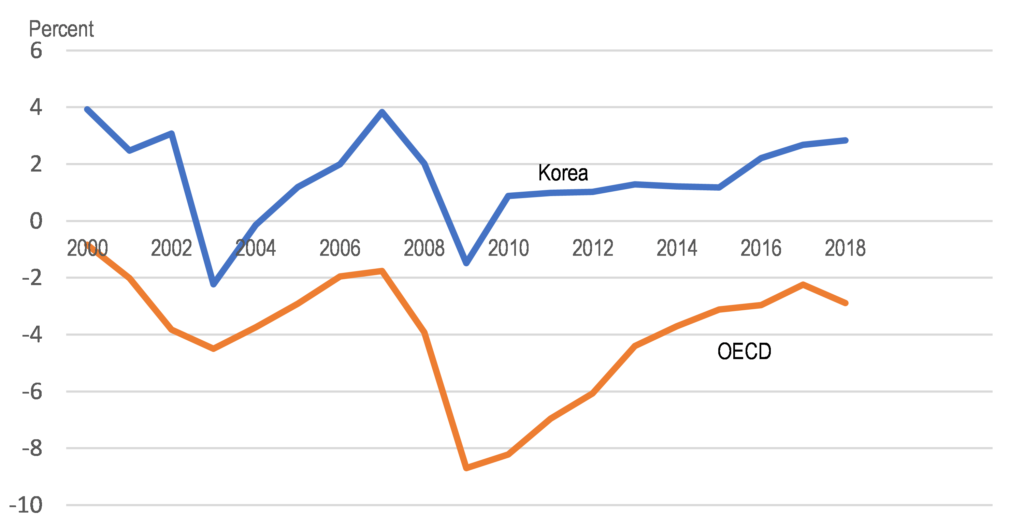

Moreover, the targeted and temporary nature of the 2008-09 fiscal support, combined with the strong economic rebound, led to a 2½ percentage-point improvement in the budget balance (from a deficit of 1.5% of GDP in 2009 to a surplus of nearly 1% in 2010) (Figure 2). In contrast, the improvement in the OECD area’s budget balance was only ½ percentage-point of GDP.

Figure 2. Korea’s budget position improved quickly after the Great Recession

General government balance as a percentage of GDP

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database.

Korea’s fiscal response to the coronavirus pandemic has also been timely. Moreover, it is targeted again on employment, which plunged 1.8% (year-on-year) in April, as the economy shed the largest number of jobs since February 1999 in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. The government aims to create at least 550,000 jobs as part of the “Korean New Deal” announced in April. Minister of Economy and Finance Nam-ki Hong said the government’s four key goals for employment are securing existing jobs through job stability, using unemployment benefits to help those who have lost their jobs, providing support for those who are in unemployment insurance blind spots and creating jobs. The public-sector jobs, though, are only temporary, as Minister Hong stated that the private sector should ultimately be responsible for maintaining and creating jobs.

Ensuring long-run fiscal sustainability

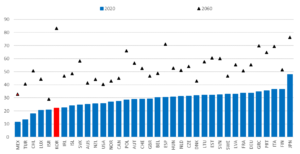

Maintaining a sound fiscal position in Korea is a priority given spending pressures, including those stemming from population aging and the potential cost of intensified economic co-operation with North Korea. With the drop in the fertility rate to below one and lengthening life expectancy, Korea faces the most rapid population aging among OECD countries. Indeed, the old-age dependency ratio (the ratio of the population aged 65 and over to the population aged 15-64) is the sixth lowest in the OECD in 2020 but it is projected to be the highest by 2060 (Figure 3). Population aging will sharply boost public social spending, which accounted for only 11% of GDP in 2018, about half of the OECD average of 20%. The government projects that under the current framework public social spending will reach 25.8% of GDP by 2060, exceeding the current OECD average. In particular, pension outlays by the National Pension System are projected to rise by 7% of GDP by 2060.

Figure 3. Korea faces the most rapid aging in the OECD

The ratio of the population aged 65 and over to the population aged 15-64

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019), World Population Prospects 2019.

Aiming to ensure sound fiscal policy and promote an efficient allocation of public expenditure, Korea introduced the National Fiscal Management Plan in 2004, as a five-year rolling Plan. The government is required to submit the Plan to the National Assembly each September, along with the budget for the following fiscal year. However, the Plan is not legally binding and its impact on fiscal policy has been limited.

It is important, therefore, to create more binding fiscal rules, as suggested last week by the Board of Audit and Inspection. It is also essential that the Plan be based on realistic assumptions about economic growth. With social spending rising, the Plan should include measures to raise revenue, while limiting any negative impact on economic growth, promoting social inclusion, and protecting the environment. A more focused and disciplined approach is important to help ensure Korea’s long-run fiscal sustainability in the face of rapid population aging.

Randall Jones is a Visiting Fellow at Columbia University and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from jonasginter’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.