The Peninsula

Pyongyang’s Deficit Soars: Won Steady But for How Long?

By William Brown

ICBMs are not the only things soaring in North Korean skies. Comprehensive second quarter data released by China Customs last week shows a huge jump in North Korea’s trade deficit with China—sharply falling North Korean exports and flat imports, a double bad combination. And, potentially troubling to the Kim regime, the composition of trade seems to be promoting market activity rather than the decrepit, but still enormous, command economy.

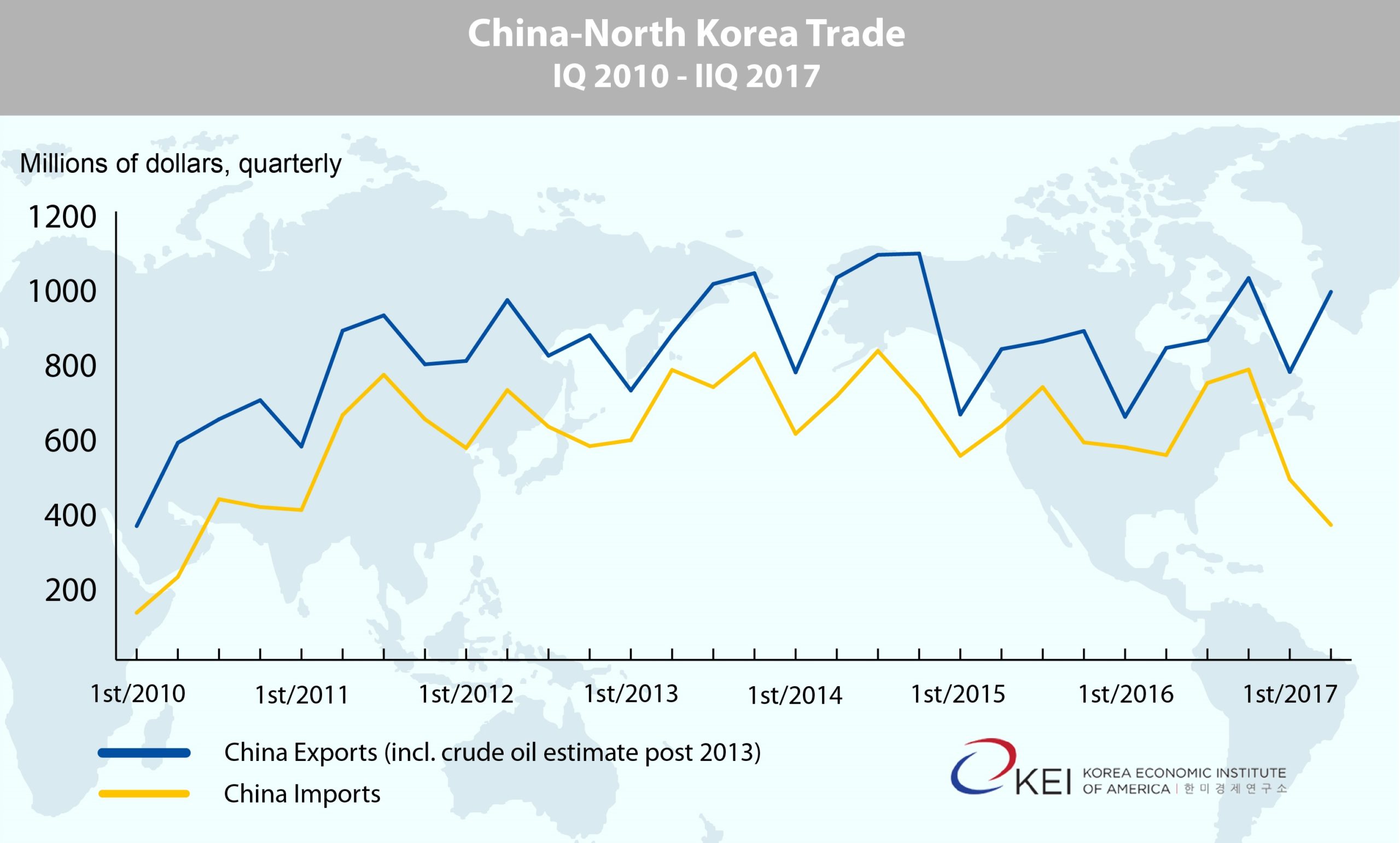

* China stopped reporting crude oil shipments in first quarter 2014 but the trade is reliably said to be continuing, probably at the old aid agreement terms which provides about 150,000 tons of crude each quarter. The charts, above and below, have added in the value of that volume at generally declining Chinese crude oil export prices–$50 million in the most recent quarter.

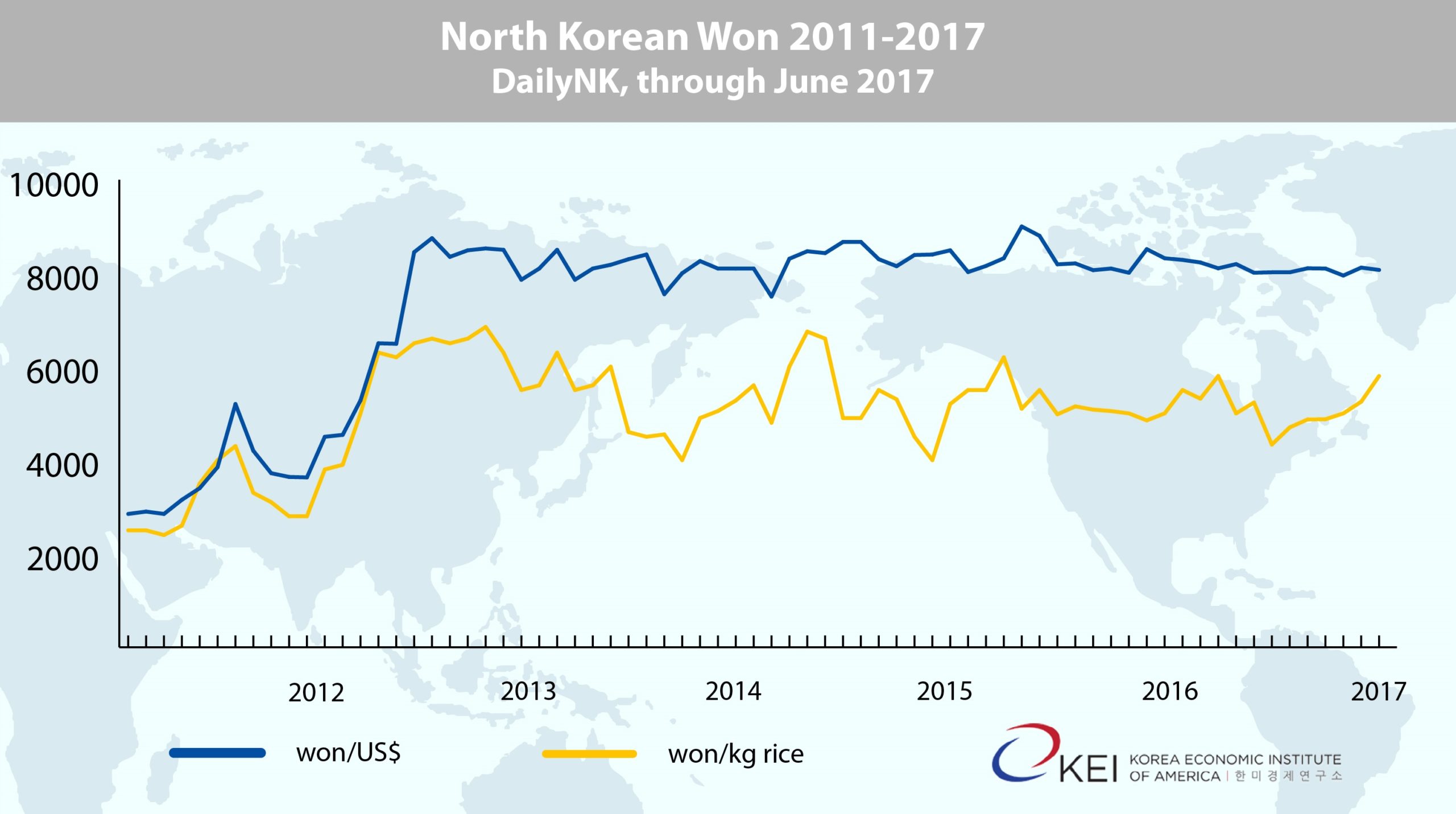

Pyongyang has been able to keep a clamp on the exchange rate—won can be traded informally for U.S. dollars in markets around the country—but likely at some cost to the government’s reserves and its ability to expand money supply without sparking inflation, and perhaps with a little help from the balloons. But food and other commodity prices, meanwhile, may be on an upswing as drought followed by flooding diminishes prospects for the critical fall rice crop, and as worries about Chinese supplies may have pushed up gasoline and diesel prices. An informal inflation index produced by DailyNK has inflation rising to a 16 percent rate in July, suggesting Kim’s signal achievement of fighting inflation may be at risk.

Officially, the Chinese data show a $174 million North Korean deficit in June and $574 million for the quarter, both at record levels. Considering China has taken its crude oil exports “off the books,” the actual North Korean deficit is probably even larger — in the graphics below we have added between $115 to $50 million each quarter to North Korean imports since 2014 to account for the oil.

How North Korea finances this large deficit in the face of sanctions on its nuclear and missile activities is not well understood, making policy analysis of those sanctions next to useless. Even South Korea’s Bank of Korea, which bravely estimates North Korean GDP, says it can’t guess at the country’s balance of payments or its hard currency reserves. But for the sake of argument, and given the trade deficit with China has averaged about $200 million a quarter for the better part of a decade, it would seem reasonable to expect that about this amount of hard currency is earned or borrowed in a combination of net trade with other countries; foreign aid to North Korea including the offset for the crude oil; UN and other international expenditures inside North Korea; small amounts of inward foreign investment and loans; remittances from overseas workers and refugees or Korean immigrant families in Japan, South Korea, China and Russia; and tourism.

- Probably to re-build domestic confidence after the country experienced a disastrous currency redenomination in 2009, followed by hyperinflation in 2010, Pyongyang’s monetary authorities appear to have fixed the unofficial won’s value at just above 8,000 won per dollar, and began to ignore the official 135 won per dollar rate. Monetary stability since then is impressive, probably owing to some combination of market price caps, restrictions on the use of foreign currency, conservativism in expanding won credit, direct intervention using the regime’s own reserves and, most interestingly, a willingness to allow legal trading and use of dollars in the market places. And now, with five years of stability, won holders appear satisfied not to chase the dollar.

- Still, the mystery of the day is why smart money dealers in Pyongyang aren’t taking advantage of the deteriorating export situation by buying up U.S. dollars and forcing a panic. Either something else is happening that we don’t know about or there is trouble ahead for the country’s always-tenuous finances. One easily can imagine another breakout in favor of the dollar and panic selling of won—hugely disruptive in North Korea’s newly forming half-market economy.

North Korean Exports Labor Intensive and Mining Products

North Korean exports to China fell to only $361 million in the second quarter, the lowest level since 2010, and even this was suppported by generally higher prices for most items. Major export commodities included:

- Apparel and other textiles accounted for almost half of its exports—$149 million, up from $145 million in second quarter 2016.

- Ferrous and non-ferrous ores rose to $78 million, up from $65 million.

- Fish product exports at $67 million, were up sharply from $31 million.

- In contrast, mineral products, including coal, was recorded at only $2 million, down from $236 million in the same period of 2016.

None of these items would appear to be big hard currency earners for the regime, although they help provide employment. Labor intensive textiles exports have grown in recent years as the industry makes better use of its antiquated mills, allowing exporters to pay workers directly in some cases and thus improving productivity of labor and capital alike. Ore exports would seem problematic, given the UN sanctions against them, but Chinese firms were said to have invested heavily in the huge Musan iron ore complex on the border with China some years ago and may now be recouping investment costs by trucking the ore over into China. This mine previously served North Korea’s largest industrial complex, the Kimchaek iron and steel mill in Chongjin, which is now dilapidated and only marginally productive. So the iron ore earnings may be coming at the expense of higher value-added steel products once exported from that plant and are likely controversial, even in North Korea, as they are thought of as a giveaway of the nation’s natural resources. China has also invested in a copper mine, and likely in other non-ferrous metals, but results from these are spotty and now largely sanctioned. Fish products are essentially traded by fishing boats, with flows going both ways depending on the season.

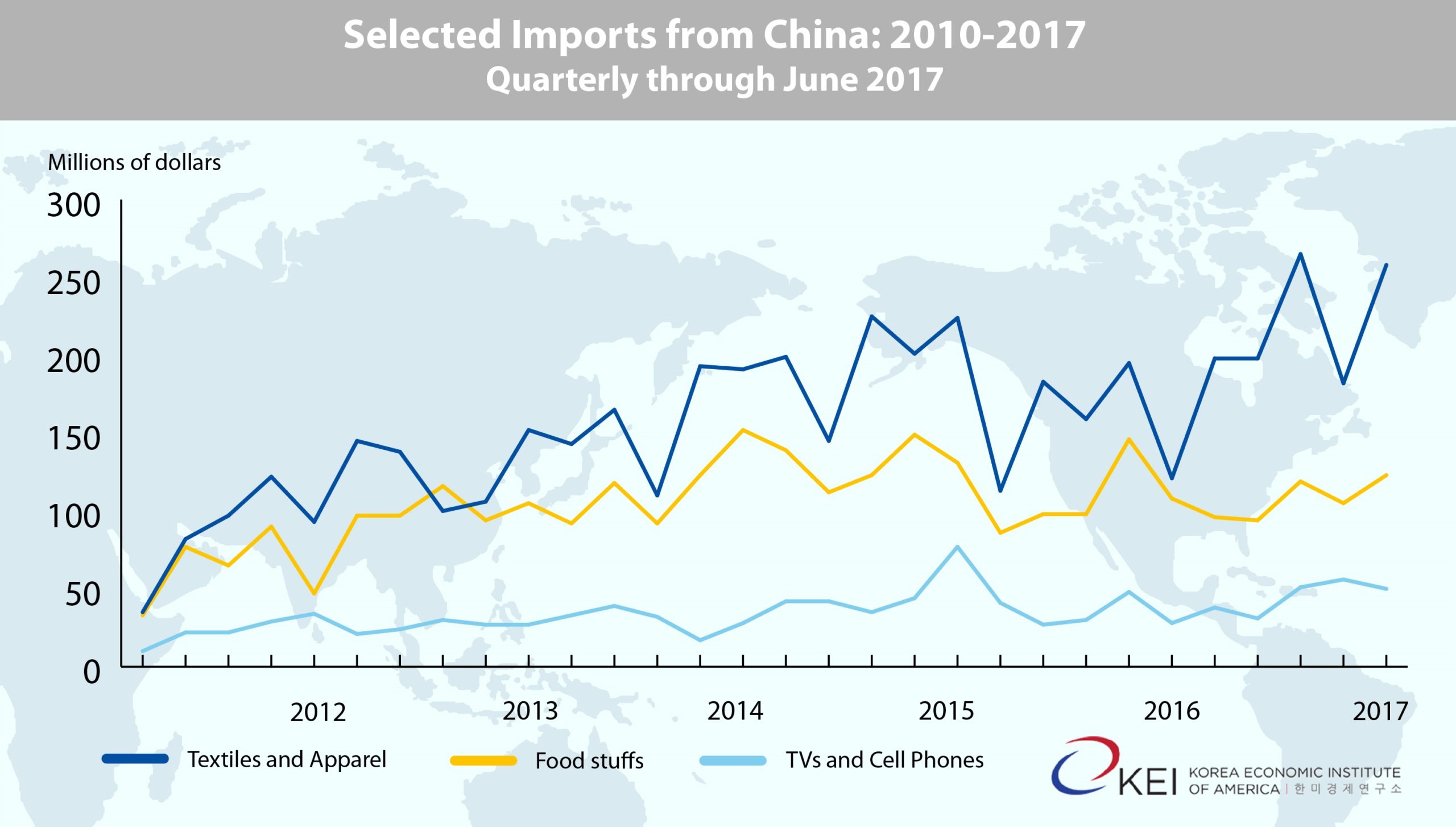

Textiles lead North Korea’s imports

Imports from China also appear to be increasingly driven by consumer rather than government or investment demand. Textiles, cell phones and television imports are growing at the expense of some industrial inputs and agricultural inputs, and cereals. Petroleum product imports, plus gasoline and diesel fuels, remain sanctioned and low.

- Textiles and apparel imports reached $258 million, up from $198 million in second quarter 2016.

- TV and cell phone imports totalled $50 million, up from $38 million.

- Food products of all kinds registered $123 million, up from $96 million.

- Diesel, gasoline, and kerosene imports were $19 million, down from $31 million, again from second quarter of 2016.

Visibility of Chinese-made consumer products among the general public is spreading the suggestion that the economy is doing fairly well—South Korea’s Bank of Korea estimated last week that North Korea’s proxy GDP rose 3.9 percent in 2016, the fastest in well over a decade and this despite the sanctions. But a large question is how far the regime will let this go, given what is clearly a big drain on limited foreign exchange. Grain imports also rose slightly in the second quarter but remain much lower than in the recent past, and may need to rise much more if the fall harvest turns out to be weak. Some grain is provided by foreign aid agencies, purchased in China and shipped to North Korea, thus counting as a North Korean import in the trade accounts, but with an offsetting credit in the (unpublished) transfers account.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. He is retired from the federal government. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Illustration by Jenna Gibson, KEI.