The Peninsula

Korea-China Relations under Xi Jinping: Strategic Cooperative Partnership... To Be Continued

By Sarah K. Yun

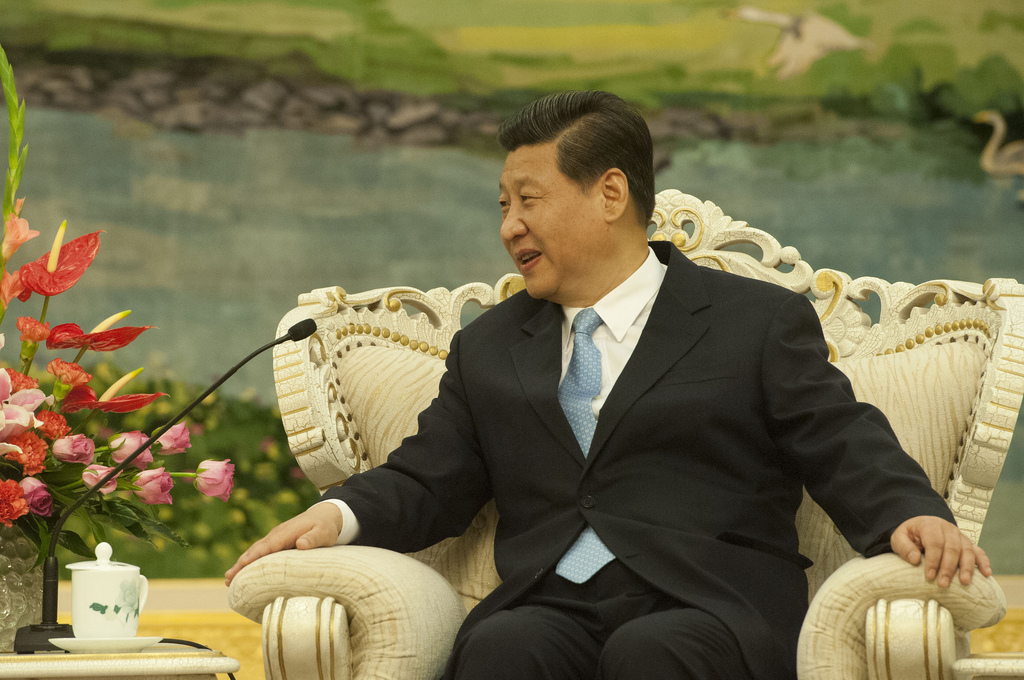

On November 8, China will begin its once-in-a-decade leadership transition at the 18th Party Congress. The current vice president Xi Jinping is expected to be named the general secretary and de facto leader of the country, while Li Keqiang is set to become prime minister, largely overseeing economic policies. Xi is also likely to succeed Hu Jintao as president in March 2013. With Korea preparing for its own leadership transition with the upcoming December presidential election, will there be any significant change in Korea-China relations?

This year marks an historic point in Korea-China relations as the two sides celebrate the 20th anniversary of establishing formal diplomatic relations. Over the last two decades the relationship has blossomed economically and broader ties were upgraded to a “strategic cooperative partnership” in 2008. Looking ahead to the new administrations, each side has enough at stake from their own national interests to maintain a positive and cooperative relationship, especially during a period of transition. China remains Korea’s largest trade and economic partner by a significant margin, and Chinese nationals are flocking to Korea in numbers that outweigh tourists from other countries. At the same time, Korea also needs China’s participation in dealing with the new North Korean leadership to alter the Kim regime’s course of isolation. On the other hand, Korea is an important regional partner for China in the midst of a changing regional landscape, managing efforts to dismantle North Korea’s nuclear program, and a relative economic slowdown.

With China still focused on its own economic development, Beijing will continue to look to its core national interest and use economic and diplomatic instruments to maintain domestic stability. China will most likely not seek to stir up too much water in Xi’s early days as he seeks to establish his authority and navigate China’s own potentially turbulent waters. As key issues for Xi will be to face increasing demands for government accountability and anti-corruption policies, managing the economic slowdown and housing bubble, as well as decreasing the gap between the rich and poor, the first era of the Xi government will be more inward looking. However, questions remain on China’s recent assertive posture in Asia, particularly on territorial issues. The impact of China’s nationalistic stance towards U.S. allies also remains to be seen.

On an individual level, Xi is a son a revolutionary general with closer military ties than Hu Jintao. Xi started his career in the Chinese Communist Party and rose through the ranks in the People’s Liberation Army. He is said to be supportive of the current leadership’s existing policies. While this means that China’s relations with Korea will continue to be cooperative, it could mean that there will be little change in its policy towards North Korea.

China’s foreign policy will also remain focused on the status quo, at least initially. China does not want instability at home, but instead wants to project a reassuring presence in the region. At the same time, China also wants to balance cooperative relations with both Koreas to be in a position of influence on the Korean peninsula. But this is more of a long-term strategy, as handling domestic challenges amidst global uncertainties and territorial tensions will be the first test of the Xi government.

However, China’s status quo stance does not necessarily equate to automatic harmony between the two countries. There are some key issues that Korea and China will have to carefully navigate under their respective new leadership. First, Korea and China will have to reinforce clear lines of communication on the potential re-engagement with North Korea and Kim Jong-un’s anticipated visit to Beijing. Second, territorial and maritime issues on Korea’s southernmost island of Ieodo and the multiple arrests of Chinese fishermen in Korean waters will make enforcement of maritime rules increasingly important. Third, the completion of negotiations on the bilateral Free Trade Agreement as well as the potential conflict of interest between the U.S.-supported Trans Pacific Partnership versus the China-supported Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership could either become an issue of cooperation or contention. Lastly, relations between the U.S., China and the U.S. allies (Korea and Japan) will continue to require careful management and navigation.

If the near term Chinese policy towards the Korean peninsula is unlikely to see a significant shift, the variable outcome of the South Korean presidential election may have a larger impact on the bilateral relations. Depending on the presidential winner in Korea and Xi’s vision for his decade-long term leadership, Korea-China relations could remain as an economic cooperative partnership or develop into a strategic cooperative partnership that actively engages various issues on a bilateral and multilateral level.

Sarah K. Yun is the Director of Public Affairs and Regional Issues for the Korea Economic Institute. The views expressed here are her own.

Photo from the Secretary of Defense’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.