The Peninsula

How the Upcoming Trump Administration Action on Steel Will Impact Korea

By Phil Eskeland

On January 22, 2018, the Trump Administration announced its decision to impose “safeguard” tariffs (otherwise known as “Section 201”) on imported large residential washing machines and solar panels. This specific trade action has only been taken by the U.S. one other time since the transformation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) framework into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994. In that instance, President George W. Bush instituted higher tariffs on steel imports in 2002 as a “safeguard” measure to assist in the recovery of the U.S. steel industry during a downturn in the U.S. economy. However, the U.S. had to prematurely end the higher steel tariffs in December 2003 because the WTO earlier ruled that the “safeguard” actions violated America’s tariff-rate commitments and authorized the affected countries to impose more than $2 billion in trade sanctions against the United States.

While it is unclear if these two recent “safeguard” actions will face a similar fate (South Korea plans to file a petition at the WTO to reverse these tariffs), it sets the precursor for the upcoming Trump Administration decision on imposing higher tariffs to protect the U.S. steel and aluminum industry on national security grounds. Most recently, President Donald Trump said during remarks when he signed the proclamation authorizing the Section 201 actions that this is emblematic of what we should expect to “see…take place over the next number of months.” These executive actions, according to President Trump “demonstrate to the world that the United States will not be taken advantage of anymore.”

While these trade actions ostensibly target China, they disproportionately hit South Korea. Even the media misplaces the emphasis with headlines that focus on China. The large residential washing machine Section 201 case focused entirely on Korean producers Samsung and LG, even though Samsung has opened an appliance plant in South Carolina and LG will soon open another facility in Tennessee to manufacture washing machines. China is also no longer the world’s top exporter of solar panels and cells to the United States – Malaysia is ranked first and South Korea is second, affecting companies such as LG Electronics, Hyundai Heavy, and Hanwaha.

There are other trade remedy decisions on the horizon, but none are more consequential for Korea as the Commerce Department investigation into the effects of steel imports on U.S. national security (otherwise known as “Section 232”). Last April, President Trump signed a memorandum directing Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, to issue a Section 232 report on steel imports. Media outlets reported last June that the release of the Commerce report was imminent (even though the law allows 270 days to complete the study), but Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis weighed in to insure that no rash action was taken after hearing negative reaction to this initiative from U.S. allies. As a result, the report was delivered to the White House on January 11, 2018. The contents of this report have not been publicly released yet, but the President has 90 days (or April 11, 2018) to institute his recommendations.

A casual observer may think this report will be primarily aimed at China because of an assumption that most U.S. steel imports come from China. However, according to the most recent release of monthly trade data from the Department of Commerce, China is ranked in 10th place in terms of steel exports to the United States. Friends and allies of the United States, including Canada, Brazil, Mexico, South Korea, Japan, Germany, and the Netherlands are ranked higher. Steel exports from China have dropped significantly during the past few years, going down from a high of 334,925 metric tons in October 2014 to 56,526 metric tons for the month of November 2017. Chinese steel now forms only 2.3 percent of imported of steel into the United States.

In 2001, the Commerce Department conducted a similar Section 232 investigation and concluded that there is “no probative evidence that imports of iron ore or semi-finished steel threaten to impair U.S. national security.” Because various factors, such as the declining use of commercially-available steel in defense products, have not significantly altered since the issuance of the prior report, one could reasonably conclude that the current Commerce study would reach a similar outcome. However, because the Commerce Department has not publicly released the current report, one must assume the investigation will focus on just a small, narrow set of facts (such as the rising share of imports as a percentage of the U.S. steel market) to justify a pre-ordained conclusion to raise tariffs and does not contain additional or clarifying information to put this issue in full context.

Steel tariffs or quotas should not be imposed using a national security rationale. The U.S. already has sufficient tools in the trade remedy toolbox to deal with allegations of “unfair trade” through the use of an open and transparent quasi-judicial processes that culminates with a public vote by six commissioners who serve on the independent and bipartisan U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). This Commerce Department report on the national security implications of steel imports was prepared behind closed doors, after just one public hearing in Washington, D.C. and a written comment period that closed on May 31, 2017. The public may not know the report’s content until after the President has made his decision to impose tariffs or import quotas.

In addition, if steel is used in defense production[1], it is usually a highly specialized steel that is not commoditized as a commercial, widely-available product. The Defense Department already has established program and policies in place, such as Diminishing Manufacturing Sources and Material Shortages (DMSMS) program and domestic preferences, to insure that it has a steady supply of any product essential to defense production. There is no need to slap across-the-board tariffs or import restraints on commercially-available steel imports to preserve the ability of the Pentagon to source a particular steel product. As a result, if the Trump Administration proceeds with implementing higher tariffs or import quotas to protect the U.S. steel industry on national security grounds, any country negatively affected by this action will easily win a WTO case, similar to the outcome on the Section 201 steel case in 2003.

Restrictions on steel imports would affect more industries than the previous two trade remedy actions on washing machines and solar panels, particularly among U.S. manufacturers who use steel to make a final end-product. The last time the U.S. took a similar trade remedy action in 2002 (Section 201), more U.S. jobs were lost than were in the entire U.S. steel industry at the time and received massive opposition from a variety of sectors, from those who manufactured automotive components to those who worked at U.S. ports. In fact, in a landmark Congressional hearing held on this issue, business owners and union workers from steel consuming industries testified together in opposition to the higher steel tariffs. Mr. Robert Herrman, who was a member of the U.S. Steelworkers Union and employed at A.J. Rose Manufacturing, an automotive parts maker in Ohio, summed it best when he asked, “Why are jobs at steel mills more important that the 250 jobs of union associates at A.J. Rose?”

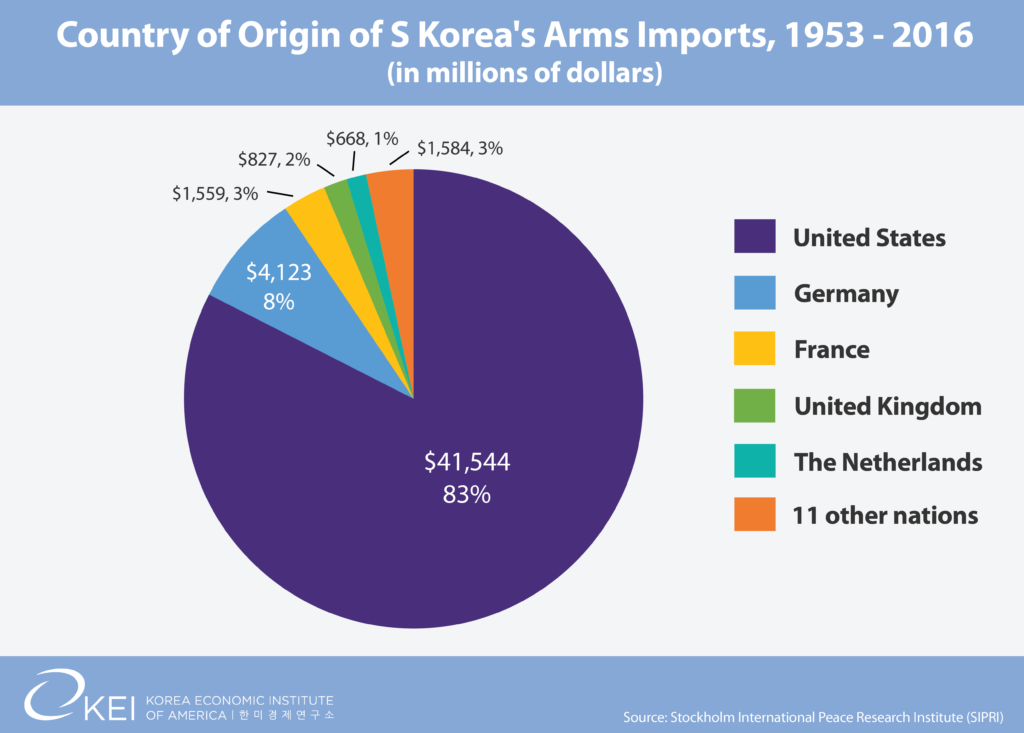

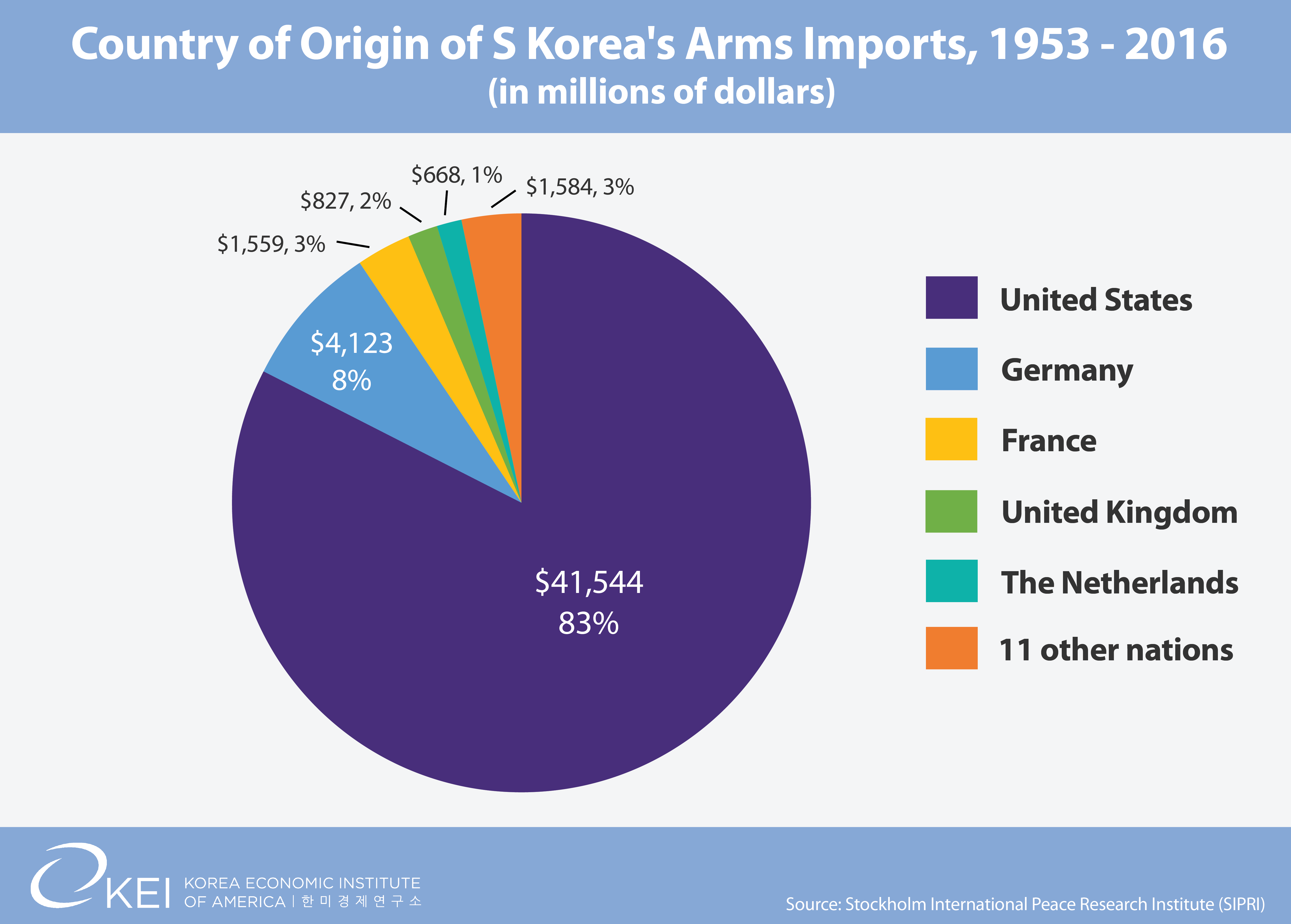

Finally, instituting across-the-board tariffs or quotas on steel for national security reasons would once again be misdirected fire against one of America’s strongest allies, the Republic of Korea (ROK), in the effort to somehow penalize China. This is particularly pernicious in light of the fact that South Korea has historically sourced most of its defense equipment from the United States (see chart). For example, during the past two years, Korea took delivery of 36 Apache helicopters. The first delivery of the estimated 40 F-35 Joint Strike Fighters (JSF) Korea has on order is expected to take place later this year. It is counterintuitive to believe that steel exports from Korea would threaten the national security of the United States when its products may be incorporated into the defense hardware that South Korea needs for its own national security. In addition, as a treaty-ally, South Korea has committed its own troops to protect the national security interests of the United States numerous times after the Korean War, including Vietnam, the Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Over 5,000 ROK forces died in these military actions to support the U.S., so it would be impertinent to imply that South Korea, through its legal exports, threatens the national security interests of the United States.

In sum, imposing higher tariffs or import restraints to safeguard the U.S. industrial base should be used only as a matter of last resort as a tool to legitimately protect U.S. national security. Otherwise, U.S. trade action on these grounds would set a bad precedent that will encourage other nations to emulate America’s behavior by erecting barriers to certain U.S. exports based on a “national security” exemption. Unless the trade remedy is carefully tailored to have carve outs and country exemptions, the U.S. would be missing the wrong target (China) and disproportionately punish a strong U.S. ally (ROK) who has protected America’s national security interests on many occasions and continues to be one of America’s best customer for defense products.

Phil Eskeland is Executive Director for Operations and Policy at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from Mouser Williams’ photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[1] Increasingly, steel is being phased out of defense production in favor of lighter and stronger materials, such as aluminum or titanium, or the need for a stealthier design, such as composites.