The Peninsula

Beyond the Data: Gender and Immigration in South Korea

South Korea’s strong economy is a significant pull factor for foreign workers, but despite a declining workforce and a need for foreign workers, Seoul implements some of the strictest immigration controls among the OECD countries.

Prior to immigration reform initiated in 2004, South Korea maintained exclusionary practices towards long-term immigration for foreign workers through “side-door” programs that enabled short-term labor immigration instead. No longer able to turn a blind eye to the swells of immigration at its borders, the general assembly introduced the Employment Permit System, aiming to increase South Korea’s national competitiveness by opening the door to accept more foreign working populations. The system outlined the Unskilled Employment Visa, which accepts foreign workers for nearly 5 years in “manufacturing, agriculture, fishery, construction, and a few service industries.”

More visas were introduced in 2007, when the National Assembly passed the Basic Act on the Treatment of Foreigners to coordinate immigration policies across government and industry levels. It primarily centered on promoting foreign worker protection and aiding married migrant workers. It also introduced the Marriage Immigration Visa, allowing a South Korean citizen to sponsor a foreign spouse.

Traditional gender roles present in South Korea impact the distribution of visas in terms of foreign work visa recipients. In this article, I examine the percent of male and female immigrant visa conditions, compared to their respective immigration totals, as a proxy to indicate patterns in how foreign workers may receive South Korean visas. Data between Unskilled Labor Visas and Marriage Immigration Visas are compared for each gender.

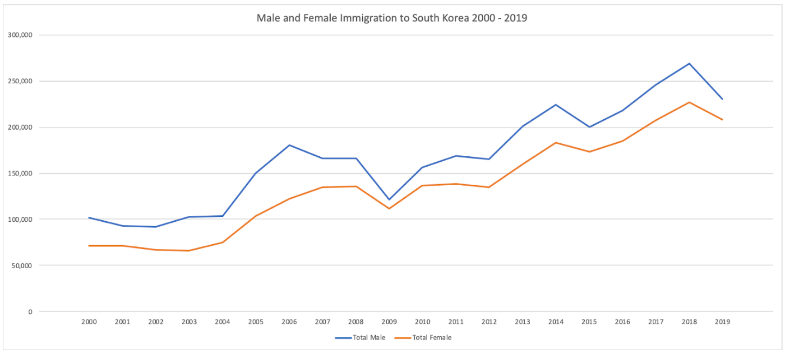

As a whole, there are consistently more male immigrants to South Korea than female immigrants. At its peak in 2018, South Korea received 266,583 male immigrants and 226,546 female immigrants.

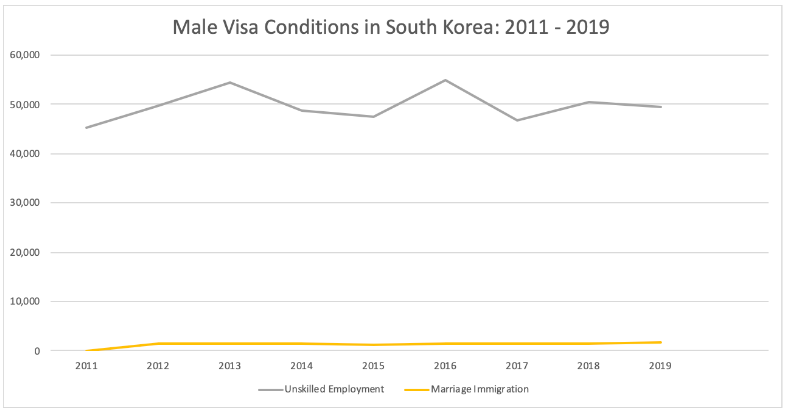

In the context of foreign workers, male immigrants are most likely to receive “Unskilled Employment” visas, an E9 visa granted through the Employment Permit System (EPS). In 2018, 50,390 male immigrants––18.9% of all male immigrants to South Korea––received visas through “Unskilled Employment” criteria, significantly more than those who received “Marriage Immigration” visas. Only 1,560 male immigrants, or 0.59%, received the latter, indicating that it is unlikely for this demographic to marry an individual in South Korea as a means of receiving a visa.

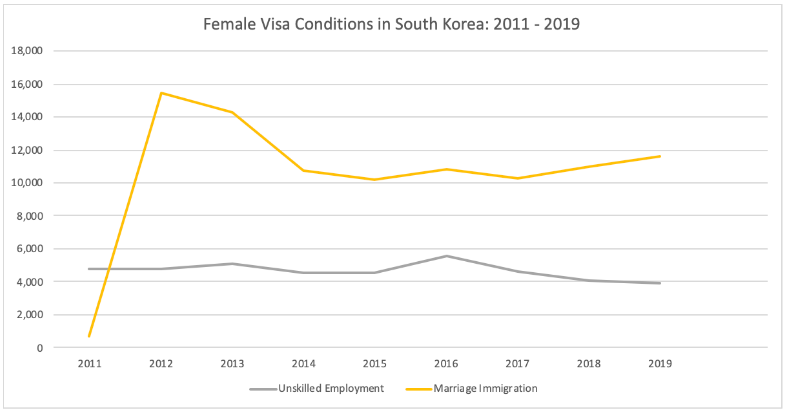

More female migrants receive visas from the “Marriage Immigration” visa category, at 4.85% of all female immigration to South Korea in 2019. Women thus are eight times more likely to receive a visa through marriage than their male counterparts. Women are much less likely than men to receive an “Unskilled Employment” visa, accounting for only 1.81% of female immigration to South Korea in 2018.

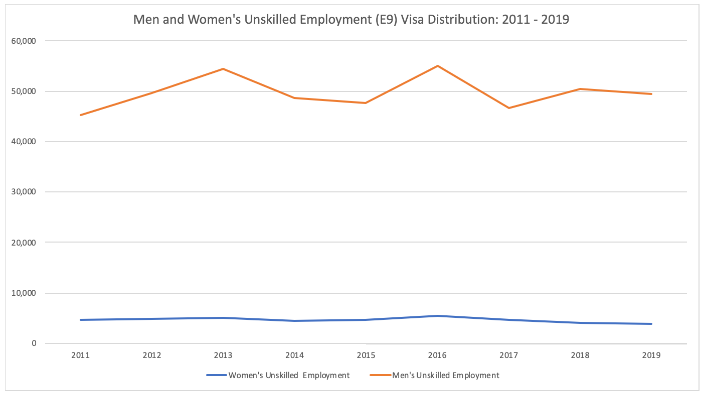

Raw immigration data reinforces the difference between men and women’s receipt of E9 visas for long-term immigration in South Korea. In 2018, 50,390 men received “Unskilled Employment” visas, compared to only 4,109 women. In the same year, 10,997 women received “Marriage Immigration” visas while 1,560 men received this long-term immigration grant.

Since larger immigration reforms began in 2004, visas granted by South Korea to male and female migrants increased significantly. The data displays a clear difference, however, in which visa is received by either gender. Male migrants primarily receive “Unskilled Labor” visas, while female migrants’ visas trend towards the “Marriage Immigration” visa. Foreign visa distribution patterns may indicate the direction the South Korean immigration policy must shift to provide greater opportunities for both genders to achieve long-term immigration, as the demand for foreign workers increases and the domestic pool of workers decreases.

Julia Fadanelli is a Research Assistant at the Korea Economic Institute of America and an undergraduate at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from VECTROTALENZIS’ photostream on flickr Creative Commons.