The Peninsula

Amid Work-Life Balance Reforms, South Korean Students Shouldn’t be Left Behind

By Kyle Ferrier

While President Moon Jae-in has been actively pursuing reforms to provide overworked South Koreans a better work-life balance, students have yet to see a comparable effort for their lives. The upcoming Suneung, South Korea’s college entrance exam, on November 15 should not only serve as a reminder of the need to relieve some of the pressure on students, but how it also contributes to some of the most challenging issues facing the country today.

The South Korean education system is consistently ranked among the best in the world, even garnering praise from U.S. President Barack Obama in 2015. However, if you talk with any young South Korean they are quick to point out the downsides of high test scores. Students spend long hours at school and the system is so competitive that most also take extra classes at cram schools known as hagwons. A 2017 study found that by age 15, South Korean students will on average have already taken 6.4 years of additional schooling. Overwhelming pressure to succeed has consistently resulted in South Korea having some of the lowest happiness and highest suicide rates among teens in the OECD. The stress culminates just before students take the Suneung, which can be life-defining.

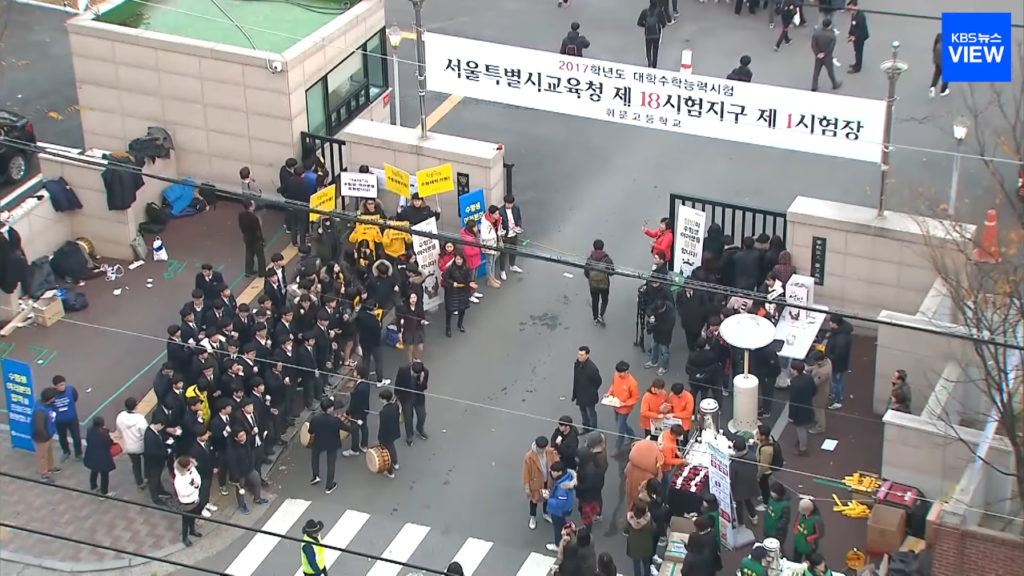

For those unfamiliar with the exam, the sheer weight of the Suneung is probably best illustrated by the nationwide coordination before and during the test.

To ensure all students arrive before the 8:40am start time, the country pushes its day back by an hour. Normal business hours start at 10am – even for financial markets – and taxis are taken off the road to cut down on normal rush hour traffic. Police officers are posted on routes to schools to cut down on possible traffic delays and escort late students. More public transportation options are also made available.

During the 25 minute English listening portion of the test, air traffic around the entirety of the country comes to a halt. Live fire military drills are also suspended during the same period.

The aim for most students isn’t to do well enough to get into a good school, but to get into one of the most prestigious universities in South Korea. Suneung scores are such an important component of college applications that the conventional wisdom is even if a student has relatively poor grades throughout high school he or she can still get into a top university with a high test score.

In the U.S., on the other hand, most elite universities place less emphasis on college entrance exams like the SAT or ACT, and some are even moving away from requiring standardized tests. Universities are also not seen as the be-all and end-all of success. About half of Americans don’t think a four-year degree is worth the cost and university enrollment rates are down since 2000.

For South Koreans, the clearest path to success starts with getting into a top university, particularly a SKY school (an acronym for Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University.) The name brands of these schools are such that they all but ensure students secure high prestige jobs and high social standing after graduating. The only way for most South Koreans to obtain a place at one of these schools and put themselves on the fast track to success is to ace the Suneung.

Because the exam is so important, South Koreans demand a level playing field, a core reason why only one version is administered at one time each year. At least part of the reason why South Koreans were so outraged by the Choi Soon-sil scandal in 2017 was that political favors were exchanged to get Choi’s daughter enrolled in a top university, completely bypassing standard admissions procedures.

Even without cheating, more well-to-do families still have a leg up. Households in the top 20 percent by income spend about 242,600 Korean won ($215) per month on cram schools while the bottom 20 percent spend 8,925 won ($8). Similar disparities in the U.S. are behind why some American universities are moving away from standardized testing, though there is limited talk of similar measures in South Korea.

The high cost of private education is also contributing to the country’s demographic decline. Despite the government’s $70 billion in incentives over the past decade, couples are not having enough children. This year the South Korean fertility rate – the average number of babies born per woman – is expected to be only 0.96, an all-time low for the country. One of the reasons couples foregoing children often cite is the high and rising education costs of ensuring a student is competitive enough for a top rate university. Total spending on private education in South Korea last year was 18.6 trillion won ($16.5 billion), up 500 billion won ($440 million) from last year.

High competition in the South Korean education system is not just linked to rising costs, but also to limited economic opportunities. The youth unemployment rate hit a 19-year high over the summer, with 338,000 25 to 34 year-olds unable to find a job. There are simply not enough high-skilled jobs for the graduates of South Korea’s university-focused education system. Yet, there are growing vocational opportunities that are either left unfilled or receive limited applications from qualified applicants. This skills mismatch in the South Korean labor market – which the OECD has pointed out for years – acts as a drag on the economy.

Reexamining the importance placed on the Suneung is more than just about finding a better work-life balance for students. It’s about social and economic inequality, population decline, and high youth unemployment – all key issues President Moon was elected to address. Facing initial setbacks in resolving these challenges, he has tried to find success through changing cabinet members and allocating more resources for these issues. However, President Moon may be better served expanding his efforts beyond the symptoms of key socioeconomic issues to address some of their root causes in the education system. The Suneung is a good place to start.

Kyle Ferrier is the Director of Academic Affairs and Research at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from KBS 뷰 photostream on Wikimedia Commons.